Why Young People Love Bad Movies: From 'Reefer Madness' To 'The Room'

A lot of people can't understand why someone would want to watch a bad movie – even one that's "so bad, it's good." Yet many bad movies find a completely intentional audience, several years after the fact.Take Ed Wood. The filmmaker died obscure and broke in 1978. Now he's a famous cult figure with an award-winning biopic to his name, whose movies are screened all over the world. The same thing is happening right now to Tommy Wiseau, the strange (French? Polish? Extraterrestrial?) director behind The Room. This film was laughed off the screen when it opened in 2003. But it's since become a beloved midnight movie that inspired a hilarious tell-all book and now, a behind-the-scenes film with serious Oscar potential: The Disaster Artist.Whether we're talking about Plan 9 from Outer Space, The Room, or some other amazingly bad movie, there's always one thing in common: young people. Young people have been instrumental in the success of all these reclaimed trash masterpieces. This is no accident. Young people are the perfect audience for bad films, for several reasons. The most basic is that college students have a great time watching these movies with their friends and a whole lot of alcohol. Some like to hone their most creative insults on these failed works, treating it like a witty bloodsport. But there's also an odd sincerity to this interest in bad movies, one that keeps young people coming back to poorly edited, horribly acted, and barely scripted films again and again.

A Brief History of Bad Movies

Bad movies can be hard to define. They're often called midnight movies, cult movies, or B-movies interchangeably. But while a midnight, cult, or B-movie can be bad, not all bad movies fit those labels. The only real defining trait is critical scorn upon release. Shoddy production values and nonsensical scripts tend to help.Television had a not insignificant role in their rise. Between 1954 and 1955, actress Maila Nurmi introduced viewers to cheap, forgotten horror films on The Vampira Show. Nurmi's Vampira served as the guide to films such as The Flying Serpent and Devil Bat's Daughter, released a decade earlier to little fanfare. This kind of television series was unique for the time and given Vampira's, well, vampy persona, it led to lots of copycats on local stations. Morgus the Magnificent entertained New Orleans audiences with his strange experiments, while Zacherley was the undertaker host to beat in New York and Philadelphia.But bad movies found an early audience in movie theaters as well, since they shared some overlap with exploitation movies. Exploitation movies had existed on the fringes of Hollywood since at least the 1930s. They rarely made it into mainstream theaters, because wide releases required a seal of approval from the Production Code Administration, a censorship body that regulated movies from 1934 to 1968. Given the content of exploitation films – which ranged from drug frenzies to sex mania – they were hardly ever submitted for consideration to the PCA. But they built a following, one that exploded in the 1960s after the censorship system collapsed.Midnight movies were also exploding in popularity around that time. Most people think midnight movies, at least as we know them, began in the 1970s with Alejandro Jodorowsky's El Topo. But the seeds were there in the previous decade. As Keith Phipps explained over at The Verge Mike Gertz started showing avant garde films at midnight at his Cinema Theatre in Los Angeles in the 1960s. He got the idea to bundle a bunch of them into "Psychedelic Film Trips #1," a package he sent to his uncle Louis Sher's theaters, also to be played at midnight. These "psychedelic" films did well, and were soon playing across America.All these movies and shows paved the way for our modern fixation with bad movies – and young moviegoers have always been their biggest champions.

Young People and Bad Cinema: A Love Affair

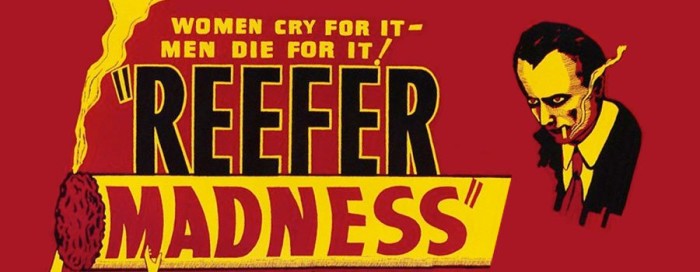

Reefer Madness, first released in 1936, is a classic example of an exploitation film. It fit neatly into a subset of that genre: the cautionary tale. Reefer Madness warned viewers that just a few joints could lead to multiple deaths, insanity, and some seriously demented piano performances. Despite that ridiculous plot, Reefer Madness likely would've been forgotten, were it not for Keith Stroup. Stroup was a recent law school grad in 1970 when he founded the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws. As part of his fundraising for the group, he began screening Reefer Madness, which he had purchased from the Library of Congress for $297. Young people thought it was a riot, especially when they smoked pot themselves, and it quickly became a hit in college towns.This is a pattern you see all the time with bad movies. They are mocked and/or forgotten upon release, only to be rediscovered by young audiences and given a second life. It was also a young fan who led so many people to Ed Wood's filmography after the director's death. Harry Medved developed a fascination with the filmmaker when he was just 17 years old. He and his brother Michael later bestowed top worst honors on Wood in their 1980 book The Golden Turkey Awards. The designation helped introduce new viewers to the eccentric director. The Medved brothers also hosted Ed Wood screenings at film festivals, brought weird clips from his movies onto daytime television shows, and developed a British series The Worst of Hollywood to showcase films like Plan 9 from Outer Space. Harry Medved remembers the Ed Wood cult truly taking hold in the early 1980s at places like UCLA, where students held an All-Day Wood Marathon in Melnitz Hall.Perhaps no single person is more responsible for rescuing bad movies from obscurity than Joel Hodgson, the creator of Mystery Science Theater. Hodgson was 28 when the first episode aired on KTMA-TV. His series was, in a way, the spiritual successor to The Vampira Show. Hodgson did not wear a low-cut black dress, opting for a jumpsuit instead, but he did introduce his viewers to dozens of old, obscure films. Or, as the opening credits put it, "cheesy movies – the worst we can find." As his alter ego Joel Robinson, Hodgson was subjected to the movies as a torture device, but ended up enjoying them instead, riffing throughout their runtime with his robot pals. Over the course of ten seasons and a recent revival, MST3K brought mass attention to now-canon bad movies, like Manos: The Hands of Fate.When MST3K writer Frank Conniff decided they should feature Manos, the movie had been totally abandoned since its 1966 premiere. Why? Manos was made by a salesman on a bet. It concerned a polyamorous cult, but featured seemingly endless, aimless shots of a family driving. The first screening made its child star cry. But its appearance on Mystery Science Theater 3000 brought it instant fame. The Manos episode became the most popular DVD in the MST3K catalog, leading to a documentary (Hotel Torgo) and a meticulous restoration of the original 16mm Manos print.Who undertook that restoration? A 26-year-old film school graduate named Ben Solovey.As these examples show, awful-awesome movies were not, historically, the easiest to find. Fans had to read the right books, watch the right shows, or go to the correct campus screenings if they wanted to discover great bad movies. But streaming platforms have made it simpler for young audiences to find and boost their next favorite bomb. Many diehard fans of The Room will tell you that they saw the "You are tearing me apart, Lisa!" clip on YouTube before they ever saw the whole film. The same is true for the ubiquitous "They're eating her!" scene from Troll 2.

Why Young People Love Bad Movies

The obvious question is, "Why do people watch this garbage?" It's been posed by scholars and concerned loved ones alike. A recent study in the journal Poetics gave an academic reason. People who like "trash films," it reasoned, tend to be film buffs. They enjoy "a broad spectrum of art and media across the traditional boundaries of high and popular culture." A movie that pushes the traditional boundaries of pop culture could be an avant garde film like Meshes of the Afternoon. Or it could be Birdemic. The good news is that, either way, it's an indication of intelligence. (So if you like bad movies, you're basically a genius.)Ironic viewing is obviously a factor here, which has led some people to argue young people are being unbearably hip. In her book No Logo, Naomi Klein suggested this is exactly what happened with Showgirls. "Six months after the movie Showgirls flopped in the theaters, for instance, MGM got wind that the sexploitation flick was doing okay on video, and not just as a quasi-respectable porno," she writes. "It seemed that groups of trendy twenty-somethings were throwing Showgirls irony parties, laughing sardonically at the implausibly poor screenplay and shrieking with horror at the aerobic sexual encounters."(This perception that young people are laughing derisively at bad movies is also what led Kurt Vonnegut to decline a dinner invitation from Hodgson, in a pretty incredible anecdote.)While snark is key for some viewers and some movies, none of that explains the genuine sincerity expressed by so many followers of terrible films. It's all over Best Worst Movie, the documentary about Troll 2. Throughout the documentary, fans show off the sequel screenplays they've written, the tattoos they've inked on their arms, the costumes they've made. They reenact scenes to rapturous cheers. They lose their minds whenever actor turned dentist George Hardy, who played the father in the movie, makes an in-person appearance. They love Troll 2 for exactly what it is. "It's genuine. There's no irony going on," one fan says. "A film that genuinely expresses a story. A totally whacked story."Young fans have a deep affection for these movies because they see in them a silly sketch they shot with friends in high school. They watch a bunch of earnest people putting everything into a profoundly dumb idea, and recognize all the dumb ideas they've had. They know these people didn't get famous, at least not in the way they imagined, from this ill-advised movie. But hey, their Shawshank parody didn't get them anywhere, either."There's a certain nostalgia factor to it," Solovey said in an interview. "If you've ever picked up a video camera and tried to make something, you recognize Manos: The Hands of Fate."Maybe you never dreamed up Torgo or Nilbog, exactly, but someone did. For young people who love bad movies, that means something. Maybe even everything.