'Boogie Nights' Turns 20: Revisiting Paul Thomas Anderson's 'Family' Masterpiece

"I got a dream of making a film that's true. True and right and dramatic."

This line of dialogue comes courtesy of porn producer Jack Horner (Burt Reynolds) early in the sprawling 1997 epic Boogie Nights, from then-upstart writer/director Paul Thomas Anderson. In the intervening period, Anderson has lived up to that dialogue, maturing into his generation's best filmmaker, the spiky and unique auteur behind Punch-Drunk Love, Inherent Vice, and the new century's best film, There Will Be Blood.

Boogie Nights, which turns 20 today, is not Anderson's first feature—that would be Hard Eight from 1996—but it's a poster child of the major concept that he's returned to in his other films. His filmography has focused on everything from porn to the oil industry to Scientology, but the core theme of his work, as highlighted by Boogie Nights, is the necessity of family.

San Fernando Valley, 1977

The actual, biological families we see in Boogie Nights are thorny and inspire heartbreak. There's the mother and father of lead character Eddie Adams (Mark Wahlberg), the boy who will eventually become porn star Dirk Diggler. Eddie's mother (Joanna Gleason) is no-nonsense to the point of being spiteful and cruel, wielding as much power as possible in their unremarkable suburban California ranch house. She mocks his intelligence, his immaturity, and his shiftless nature. Eddie, however, is convinced that he has "something special" to offer the world, but doesn't seem to have a future outside of getting paid a few bucks to display his prodigiously large penis in the back alleys of the flashy nightclub where he works.

His mother, in her own sad way, is as lost as everyone else in the film is: she resents the domestic lifestyle in which she operates, almost as much as she resents Eddie's father, who barely talks to her or his son. When Eddie leaves for good, after a final shouting match (one in which his dad sits, emotionally paralyzed, in his bedroom), it's both pitiable and reasonable on both sides. Were it not for an offer to join Jack at his ranch house for future pornographic work, Eddie would be exactly as hopeless as his mother pegs him to be. Eddie's better off away from his mother, and she from him, no matter how much she might have tried to steer him on a more respectable path.

The other view into a fractured biological family is even more devastating, amidst all the madness occurring in the middle of a story about porno. If Jack functions as the surrogate father of those who work for him, the surrogate mother is Amber Waves (Julianne Moore), introduced by Jack as "a real and wonderful mother to all those who need love." But Amber needs love too, and struggles to reconnect with her young son, Andy, to get it. By the time the movie starts, in 1977, Amber has already lost touch with Andy for hard-to-dispute reasons: her work in pornographic movies and her rampant drug use. Later, after six years have passed, Amber attempts to regain visitation rights but is unable to argue against her ex-husband's claims that her son should never have to visit "a house of drugs and prostitution and pornography."

Little is shown of the court hearing, because all we need to know is what we see when Amber, afterwards, is wracked with emotion, sobbing her eyes out outside the courthouse. In both of these cases, it's extremely easy to see the perspective of the two people pushing back against Eddie and Amber. And in both cases, the porn actors wind up as the vastly more relatable figures, because of how empathetic Anderson is towards his characters. Neither Amber nor Eddie are treated scornfully by the script. The work they do may seem (and may be) less than "worthy," whatever that could mean, but he allows them a passionate humanity that other directors and writers wouldn't.

The '80s

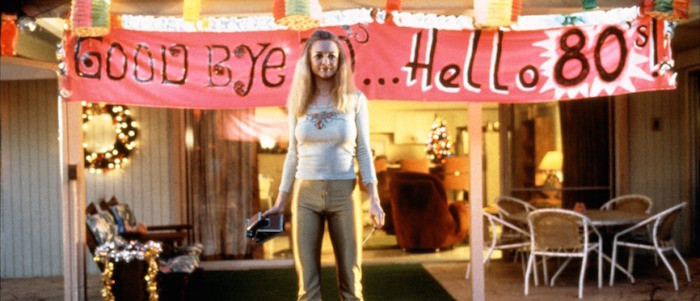

Where real families let them down, the characters of Boogie Nights look to each other. With Jack and Amber as the parental units, they have a handful of would-be children: Eddie/Dirk, Reed Rothchild (John C. Reilly), Buck Swope (Don Cheadle), and Rollergirl (Heather Graham). Various elements conspire to separate the group in the second half of the film; Anderson is able to essentially divide the rise and fall of the characters by decade. The first hour or so, up to the end of a party to celebrate the arrival of a new decade, takes place in the late 1970s, where the rest takes place in the first few years of the 80s. That party is abruptly brought to a horrifying close when assistant director Little Bill (William H. Macy) kills his cheating wife, her lover, and then himself in the middle of the revelry, breaking up his own family before the ripple effect hits his colleagues.

The 1980s are a low period for everyone, beginning when Jack has to grimly accept that the future of pornography is video instead of film. Then, Dirk gets too high on his own supply (figuratively and literally) and tries to continue his acting and music career with Reed and a couple of hangers-on, the hopelessly besotted Scotty (Philip Seymour Hoffman) and arrogant fellow porn actor Todd (Thomas Jane). Buck, trying to break out of the porno business, wants to open up a stereo store while refusing to change his identity as a black man who adores the country-Western scene; he keeps failing because financial institutions only see his adult-film past. Rollergirl and Amber, unable to fix their specific troubled lives, try to seek solace with each other. (One of the saddest moments in the film comes when a coked-out Rollergirl asks to call an equally high Amber "Mom," to which the older woman happily assents.)

Two specific sections detail the darkest moments these characters have before they return to their makeshift family. First, there's a series of scenes that all take place on Sunday, December 11, 1983 (as PTA specifically notes in a subtitle). Dirk, hanging out in a parking lot, is approached by a young man who lures him into performing sexual favors before beating him up. Meanwhile, Jack and Rollergirl drive by in a limo, attempting an innovation in adult cinema where they pick up a random man to film sex in real time; the idea goes south when Rollergirl realizes that the man they've picked up was a high-school classmate of hers who's very familiar with her extracurricular activities. Finally, Buck and his bride (Melora Walters), after another failed loan application, stop for donuts, during which Buck winds up in the middle of a robbery turned deadly. Of the three stories, only Buck's remotely approaches a happy ending: though everyone else in the donut shop ends up dead, he lives and chooses to steal the robber's cash to help open his store.

The latter, and later, scene is dryly subtitled "Long Way Down (One Last Thing)". It's possibly Boogie Nights' most well known sequence, when Dirk, Reed, and Todd go to the house of an infamous drug dealer (Alfred Molina) to swindle him out of money. The sequence, inspired by the nightmarish Wonderland case involving real-life porn star John Holmes, is quintessential Anderson: unnerving (the dealer's buddy keeps lighting firecrackers inside the house), unexpectedly funny (Molina dances and gyrates wildly to Night Ranger's "Sister Christian" playing on his stereo), and harrowing (courtesy of a long shot of Dirk realizing how low he's stooped).

The scene culminates with more bloody violence, as Todd is shot and killed by Molina's character and Dirk and Reed barely escape with their lives. It sets in motion Dirk's choice to return to Jack's fold, begging the bearded impresario to take him back. The scene speaks to one of Paul Thomas Anderson's greatest talents as a filmmaker: he is exceptionally adept at throwing audiences off. As soon as Dirk and company enter the dealer's house, we hear firecrackers going off, suggesting that whatever follows will be just as unpredictable.

Long Way Down

As warped as it is, this surrogate family is better together (still making new movies by the end) than they are apart. They are arguably much better off than if they'd stayed put with their actual families. Few characters in Anderson's filmography do well with their actual families anyway, creating new ones instead. Magnolia, an even more expansive opus from 1999, depicts handfuls of families rent asunder by past cruelties inflicted by patriarchs.

There is Jimmy Gator (Philip Baker Hall, in his second paternal role for Anderson, after Hard Eight), whose infidelities and possible molestation of his own daughter makes it so his wife is justifiably unwilling to spend time being sympathetic to him even as he suffers from terminal cancer. There is Earl Partridge (Jason Robards), the TV producer whose callous treatment of his wife and son has led the child to grow up to be a misogynistic motivational speaker who inspires other men to treat women terribly in hopes of getting them in bed. And there is Rick Spector (Michael Bowen), whose son Stanley is gifted beyond belief, but who forces his son to utilize that gift on the game show Jimmy produces instead of being a loving father.

The fathers in this film, seen and unseen are truly toxic. Consider Stanley's adult analogue, William H. Macy's bespectacled character Donnie Smith. Donnie was (and is) just as gifted, and was the original "Quiz Kid" on the same game show. Now, he's a desperately lonely gay man unable to find love, even at a local dive bar. We can only imagine how bad his childhood and father were. Only the elderly fathers in Magnolia try to gain some kind of redemption, though they don't deserve any.

There Will Be Blood is both more sprawling and more intimate than either Magnolia or Boogie Nights. While it's over 150 minutes, its primary focus is just one character, the tyrannical oil magnate Daniel Plainview (Daniel Day-Lewis). Plainview begins the film as a simple prospector who strikes it big in the hills of California at the turn of the 20th century. The mostly silent first half-hour ends not just with Plainview's first triumph, but also with him choosing to take on the role of father to the unnamed son of one of the men working with him, who dies in an accident on the job. Years later, the boy, H.W., sits next to Plainview when he works at his "family" business, going from town to town as he convinces people to drill on their land for black gold.

By the end of the film, a now-deaf H.W. is striking out on his own to Plainview's fury and distaste; their last exchange includes Plainview shouting that H.W. was always just "a bastard in a basket." In the film's final moments, before Plainview has his last confrontation with the oily religious type Eli Sunday (Paul Dano), he seems to flash back to simpler times with H.W. His latent cruelty masks the reality that he did feel a closeness to the boy that he can never get back.

Sunday, it should be noted, often feels like another surrogate son, if a black-sheep type. Though he constantly butts up against Plainview, the two men representing religion and capitalism, Eli seems more aligned to the older man's sensibility than that of his own father, who he derides as weak and stupid before physically attacking him at one point. Plainview, in the end, murders Eli, but only after Eli desperately comes to him, hat in hand, asking for help in a way he feels will be advantageous to both of them.

Anderson's follow-up, the 2012 drama The Master, endured much controversy because of its unavoidable connections to the genesis of Scientology and its creator, L. Ron Hubbard. The character who Philip Seymour Hoffman plays in the film, Lancaster Dodd, isn't exactly Hubbard, but the parallels are present. Yet the true focus of the film is on the undeniable, inexplicable bond that Dodd shares with vagrant and veteran Freddie Quell (Joaquin Phoenix, in a career-best performance).

The two men are close enough in age so it's not exactly a father-son dynamic, but Lancaster maintains a constant paternal air, and the film emphasizes a similarly constant sense that Freddie is trying to gain the approval of this enigmatic figure. So much of the film is oblique—their final meeting in London at first seems predicated on a call out of the blue from Lancaster to Freddie, until it becomes clear that Freddie only dreamed the call—but their dynamic, and the sense that Freddie is seeking a family to replace the one he lost after serving in World War II, is enough to make the film a thematic sibling to the other Anderson films here.

(One Last Thing)

In a massive and fascinating oral history of Boogie Nights at the now-defunct site Grantland, Anderson's longtime cinematographer Robert Elswit said, "Paul's movies are about really one thing: families. They're about someone trying to create a family, find a family, get rid of the one they have, create a new one." Boogie Nights, more than the others, is very much about this notion of family, creating anew to replace the dysfunctional one that exists. In spite of the inherently ridiculous idea of a group of porn stars being a family, there's nothing treated more seriously in the film.

Both in the film's high moments—like one of the early pool parties at Jack's house, which ends with Eddie revealing the name he's chosen for his porn-star persona—and its low moments, Boogie Nights celebrates the idea of a group of like-minded individuals working together and gaining strength from that unity. Just as there were 20 years separating the release of Boogie Nights from the time period it depicts, we're now 20 years removed from the film's unveiling. Time has been exceptionally kind to this film, boasting some of its ensemble's finest performances, from Wahlberg to Reynolds. Anderson's career has expanded and grown more introspective, but Boogie Nights was, and still is, a blast of thrilling emotion, joy, vitality, and empathy.