The Unpopular Opinion: 'Blade Runner' And 'Alien' Are The Only Good Ridley Scott Movies

(Welcome to The Unpopular Opinion, a series where a writer goes to the defense of a much-maligned film or sets their sights on a movie seemingly beloved by all. In this edition: Ridley Scott has only made two good movies...and the reason why they're good explains the rest of his weaker filmography.)

Sir Ridley Scott's 40-year career is marked as much by its successes as it is by his chameleonic willingness to jump from genre to genre on an almost annual basis. This year alone, Scott has directed the grim sci-fi film Alien: Covenant and is following it up in December with All the Money in the World, a true-story crime drama about kidnappers trying to extort industrialist J. Paul Getty. His past films include the nihilistic thriller The Counselor, the light dramedy A Good Year, the con caper Matchstick Men, the sci-fi adventure The Martian, and on and on and on.

But the films that loom largest over Scott's career are two of his earliest: Alien and Blade Runner, the latter of which received a long-awaited sequel last week in the form of Blade Runner 2049. Considering that both Alien and Blade Runner have gotten second lives of sorts in 2017, I feel compelled to come clean to my fellow cinephiles: for me, these are the only good Ridley Scott movies.

A Beautiful But Cold Filmmaker

Yes, I know, I've almost certainly lost you already. I can hear you, talking back to your smartphone or your laptop: "What about Gladiator? What about Black Hawk Down? What about Black Rain?" (Okay, maybe there aren't many people asking about that last one.) Scott has worked with some of the best actors in the industry, from Matt Damon to Denzel Washington to Javier Bardem to Geena Davis to Anthony Hopkins. And his willingness to move within various genres might suggest that he's flexible enough as a director to bring some kind of stylistic flourishes into disparate types of stories.

In general, it's to Scott's credit that he can jump from movies like Thelma & Louise to Hannibal, and manage to not disrupt the storytelling with some unavoidably auteuristic presence. Here's the unfortunate flip side: Scott's filmmaking style, at least until the last few years, has marked him as something closer to a journeyman instead of an auteur. Prometheus and Alien: Covenant suggest that he does have an auteurist streak outside of the flashy visuals present in his works. In those Alien prequels, he leans on a bleak critique of humanity via the android character David (Michael Fassbender), who is fascinated by humankind inasmuch as he can perform experiments on unwilling participants to presumably push them towards a new stage of evolution.

I would not argue that Ridley Scott's films, aside from the aforementioned two pillars of modern science-fiction filmmaking, are truly awful. But for me, they primarily fall flat because they lack emotion. In this respect, it makes perfect sense that Scott seems to ally himself with David in Prometheus and Covenant, as opposed to the human characters fending off early versions of the Xenomorphs as well as the nefarious android.

Both Prometheus and Covenant could have chosen to document the gradual arc of a cold and unfeeling robot that learns to embrace and understand humanity, or one that attempts to grasp the meaning of human life and, in failing, chooses to spurn his creators. Considering that David, in both films, is essentially trying to eradicate humans through his experiments without much in the way of understanding how we tick, that's clearly not the case. Cold or not, David's charismatic presence is keenly felt in both of Scott's good films. The films Scott directed between the original Blade Runner and those Alien prequels have an absence of such charisma, making it so they rely heavily on atmosphere and mood, often at the expense of fully fleshed out screenplays and performances.

A Distinct Lack of Emotion

Of his other movies, the one that I come closest to liking is Thelma & Louise, primarily because it's fortunate enough to have such expressive performers like Davis, Susan Sarandon, Brad Pitt, and Harvey Keitel. The movie has at least one iconic image, possibly the most memorable outside of anything in Alien and Blade Runner among Scott's filmography: the eponymous friends driving off a cliff in a convertible, choosing death over being caught by the cops for the antics preceding the finale.

This choice, a feminine take on Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid but vastly more heartbreaking, is striking enough, and both Davis and Sarandon are quite good in the film. What they bring to the film, what brings it very close to working on the whole, is exactly what is lacking from so many of Scott's films: emotion. But two lead performers, as wonderful as they are, aren't enough to save the overall film.

And so it goes with so many of Scott's films. He's able to construct visually striking tableaux, whether it's the battles in Gladiator, the wartime chaos in Black Hawk Down, or the nihilistic miasma of Prometheus, but does so at a remove. Even in the films where characters ostensibly have an emotional core and arc, like the Best Picture-winning Gladiator, I always find myself unable to connect to whatever's happening on screen. (Even if this is a specific problem with me and Scott, the frequency to which it occurs with so many of his films suggests a consistency to his work, if nothing else.)

Robots and Monsters

In a warped way, it's really no wonder that Scott's two best films allow him to both immerse an audience in atmosphere and comment on the human condition without inducing a lot of dramatics into the situation. Alien isn't just one of the great science-fiction/horror films; it's a great film overall. The 1979 genre mashup has only nine characters (if you count both "Mother," the computer system that represents the faceless corporation overseeing the ship where the film largely takes place, and the monster itself), and is typified by its no-nonsense, blue-collar characters. The first half of the film gradually introduces the various power dynamics occurring within the Nostromo, a spaceship heading back to Earth after its crew members finish a multi-year job, as they're tasked by Mother to explore a mysterious planet sending out an enigmatic transmission.

Once the alien they find on that planet starts to wreak havoc on the Nostromo, and the crew gets picked off one by one, there's still only a slow burn of emotion. Even in the film's most disturbing scene, as Sigourney Weaver's Ripley is nearly suffocated by the ship's science officer Ash (Ian Holm), an android in disguise, the terror is expressed in images as opposed to dialogue and score. The noises we hear—the struggles on both ends, the inexplicable shrieking emanating from Ash—are that much more startling because they seem so unlike the rest of the film. The characters rarely shout, making the few outbursts so much more powerful. After Ash has been removed from the situation, and the numbers dwindle further, Ripley realizes that she and her crew were expendable, as detailed by the other non-human character, Mother. The invisible corporation driving the Nostromo's mission is far more interested in the Xenomorph than in the humans who bring it back.

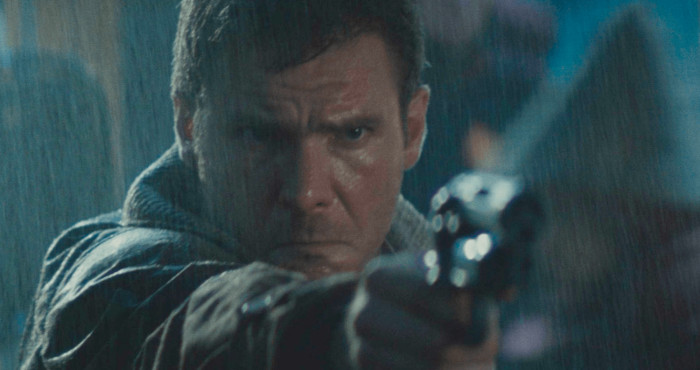

Ash's attempt (and Mother's) to kill Ripley is mirrored and furthered in Blade Runner. The 1982 film, in any of its various iterations, is all about what it means to be human. Ostensibly, it's a sci-fi story with neo-noir trappings in which Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) tries to hunt and kill "replicants," the film's word for robots who work as slave labor on and off-world. The quartet of replicants Rick has to capture are back on Earth, in Los Angeles 2019, to literally meet and confront their maker, Eldon Tyrell (Joe Turkel, in Coke-bottle glasses), in the hopes of having their four-year lifespans furthered. As the story progresses, Rick not only meets and falls for another replicant, Rachael (Sean Young), but he begins to internally question his own humanity.

By the end, the film's most charismatic character, replicant Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer), kills Tyrell by crushing his skull and gouging out his eyes. Batty is perhaps the single best character in any Ridley Scott film, and feels like the protean ideal that Fassbender is striving for in the Alien prequels. It's in no small part because his quest for meaning and purpose in a "life" full of drudgery and forced order feels like what Scott is trying to accomplish with so many of his films. Batty is the film's antagonist, sure. But Scott gives Batty close to equal time to Deckard, the literal title character, almost siding with the presumed baddie. If there is anything we remember from Blade Runner, aside from the remarkable set design and special effects, it's Batty's famous "tears in rain" monologue before his operating system runs out and he dies. Batty is not a hero, exactly, but in a film whose characters are constantly wondering whether or not they're even human, the character Scott relates most to is robotic in nature.

A Necessary Blade Runner 2049 Tangent

Now, we have Blade Runner 2049, a film that Scott only produced because of his largely busy year behind the camera. But 2049 is very much in line with Scott's original vision. Just as the question of what it means to be human was at the core of the original, it's very much at the core of the sequel. (Spoilers for the new movie ahead, so consider yourself duly warned.) Rick Deckard does show up in 2049, but is far from the lead of the picture. Instead, the story focuses on a new blade runner three decades later, Agent K (Ryan Gosling). Much has changed since the events of the first film: the Tyrell Corporation is bankrupt and the newly designed replicants don't need to be "retired." So agents like K only track down the last remaining replicants from the Tyrell era. When we first see K, he confronts a particularly large replicant (Dave Bautista) who's especially disdainful of the blade runner...because he recognizes that K is also a replicant.

Yes, there's the first turn of the screw (occurring roughly 5 minutes into the movie): where we once wondered if Rick Deckard was human or replicant, there is initially no debate about K. The real crux of the film, though, is the reverse question. After dealing with Bautista's character, K discovers a buried box of bones, that of a female replicant who died in childbirth. The next turn of the screw is logical enough if you're thinking ahead: the dead woman was Rachael, and Rick was the father. K soon believes, terrified at his own reality, that he is the missing child, proof that a replicant can reproduce, proof that would upend the entirety of society in 2049. One of his supposedly implanted childhood memories turns out to be real: one in which a child runs away from a group of bullies while holding a treasured totem, a tiny wooden horse. But when K tries to locate the origins of this mysterious hybrid child (whether or not he is that child) by investigating the orphanage where they were raised, he realizes he's walking through the same place within his memories and is even able to find where the horse was hidden for years.

Perhaps the greatest irony of Blade Runner 2049 is that it remains elusive on one question: is Rick Deckard human or replicant? The movie eventually reveals that K's existential crisis is, in its own way, a Trojan horse just like the miniaturized one he "remembered." (K's memory is real, but is not his memory.) Deckard, who K finds in the ruins of a deserted casino, remains as mysterious as ever. The older man harbors, naturally, guilt for having left his child at birth, but when he is brought to Niander Wallace (Jared Leto), whose corporation has supplanted Tyrell in making replicants, we are once again given hints as to his possible identity. Early on, when K tries to pinpoint Deckard's whereabouts, he visits the man's old partner, Gaff (Edward James Olmos), who says Deckard is "retired," which has a very loaded double meaning in these films. But where K's identity is clearly defined at the end of the film, Deckard's remains a mystery.

Fascination With the Unemotional

Of course, if you ask Ridley Scott, the answer doesn't need to be clarified in Blade Runner 2049 because it was answered in Blade Runner: Deckard, in his view, is a replicant. Thus, the most human characters in that neo-noir aren't even human. And if you believe Scott, then the same is true of Blade Runner 2049; the humans we see treat "skin jobs" like K either cruelly or dismissively. Director Denis Villeneuve does vastly improve on one aspect of the original: Blade Runner 2049 is a lot more emotional, sentimental even, than its predecessor. Thank goodness. The perceived lack of humanity within humankind is something that Ridley Scott's been fascinated by for his entire career, and is a big part of why Alien and Blade Runner work so well. But it's why so many of his other films falter for me: being fascinated by the unemotional means you wind up with dramatically inert stories.