How Being A Parent Changes The Way You Watch 'Close Encounters Of The Third Kind'

Before I became a father, one of the most common things that would annoy me when talking to other people who were also parents was some version of the following: "Well, you can't really understand it unless you have kids." I would roll my eyes behind their backs. I'd tell myself that having kids can make a major impact on your life, but you can still question a parent's choices or wonder if you'd do things differently without having kids yourself. I am still not a huge fan of this phrase – we can all empathize with someone else, even if we don't walk in their shoes. But it's a phrase I kept thinking about when I sat down to watch the 4K restoration of Steven Spielberg's Close Encounters of the Third Kind this past weekend, as it celebrates its 40th anniversary.

The Privilege of Youth

An easy way to criticize Spielberg's films is to dub them mawkish or sappy. All the grit and violence of Saving Private Ryan, for some, could be undercut by the final moments of almost operatic emotion at a gravesite in the present day. All the dinosaur action of Jurassic Park might not absolve the subplot about a paleontologist being encouraged to buddy up with a kid so he can unlock his innate paternal tendencies. This criticism isn't entirely unfounded, but only tracks to a certain extent within his filmography. One notable exception, AI: Artificial Intelligence, which is squarely about childhood and humanity, is Spielberg's most recent writing credit and it's exceptionally bleak. Through the mid-1980s, most of his work features a harsh subtext, if not actual text, when focusing on families and kids: the depiction of a child being brutally eaten in Jaws, the way that a possessed Indiana Jones attacks his friendly sidekick Short Round in Temple of Doom; even in Poltergeist, which Spielberg only technically produced, the peril that kids are placed into isn't undercut by a lot of sentimentality.

Close Encounters of the Third Kind is different only because Spielberg's acknowledged that the darkness of that film's family unit wouldn't exist if he made it after he had children. In a making-of documentary commemorating the 20th anniversary of the 1977 film, he said, "I would never have made Close Encounters the way I made it in '77, because I have a family that I would never leave. That was just the privilege of youth." Those last four words are a fascinating encapsulation of the character arc for Roy Neary (Richard Dreyfuss), the inquisitive and obsessive lead of Close Encounters, an Indiana phone-lineman who sees a group of alien spacecrafts fly over his head one night, eventually leading him to a journey to Devils Tower, Wyoming, where he takes part in first contact between humankind and extraterrestrial life. This quest for answers, to discover what his visions mean, is thrilling, but has the dark undercurrent of Roy alienating and driving away his wife (Teri Garr) and his three kids.

Seeing Close Encounters of the Third Kind on the big screen is a largely wondrous experience. Even as a young director, Spielberg could craft a stirring spectacle like few others. The final third of the film, in which Roy and Jillian Guiler (Melinda Dillon) witness the symphonic meeting between man and alien, is truly awe-inspiring. What precedes this is both compelling and enervating to me. The way that Spielberg depicts Roy's family has always seemed off-putting, perhaps in a similar fashion to how Spielberg admits he wouldn't tell the story the same way anymore. I could echo his comments and suggest that, now that I'm a husband and father, the changes in my life over the last few years have changed my perception of the film.

That could be true of any movie; every time you rewatch it, you're at a different emotional place, so your reaction may shift. As much as I can heartily recommend seeing Close Encounters in your local theater (let's be fair: you don't need my recommendation), I will just as easily acknowledge how queasy the scenes of Roy unable to deal with his family and his middle-class life make me feel, and have always made me feel. It's not that Roy has to be likable, or that a movie's characters must be morally good or punished for moral failings. It's that the movie, unlike AI, that other sci-fi epic Spielberg wrote and deals with children, never reconciles the messiness of the first 90 minutes, giving Roy a happy ending without consequences for his actions.

When You Wish Upon a Star

In the first 90 or so minutes, there's a constant battle depicted in Roy's journey. Some part of him seems to know he should be an active father and husband, but he desperately wants to discover the meaning of the mysterious visions he keeps having of Devils Tower. He wants to know that the UFOs he saw, the ones whose appearance cost him his job, had some higher purpose instead of being a random occurrence.

Arguably, from Roy's first appearance in the film, playing with an extensive model train set as "When You Wish Upon a Star" plays quietly in the background, he's already a bit mentally checked out from his familial duties. But by the last time he interacts with his family, tossing garbage from outside their Muncie house indoors so he can build a large-scale replica sculpture of Devils Tower, he's far gone. Roy's family is out of sight, out of mind as he drives across the country to chase the feeling of something beyond the horizon. In the climactic moments, Roy's dream becomes reality; the metaphorical star on which he wished pays off. He steps aboard the multi-colored mothership as it leaves Earth for points unknown.

Once Spielberg became a family man, many of his films seem to reflect a softer, less complex depiction of family life. Even a post-9/11 blockbuster like War of the Worlds introduces a contentious father-son relationship and reunites the family unit in the final moments, stretching plausibility beyond the breaking point. In what surely can't be a coincidence, the only film Spielberg has directed and solely written in the 40 years since Close Encounters of the Third Kind is AI, the only other film he's made to a) directly confront a fractious family dynamic and b) heavily invoke Pinocchio.

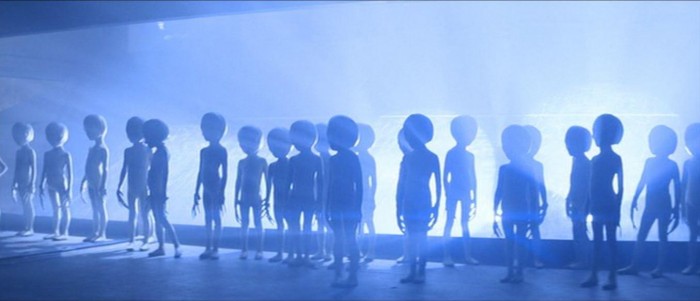

Close Encounters takes a musical cue from "When You Wish Upon a Star," but feels more in line with Disney's Peter Pan. Roy alienates his family, in part because he's too immature to be a parent or a spouse. His choices are never callous — Roy not only inspires his kids to cry as he sculpts Devils Tower out of mashed potatoes; he does so as well, knowing what he must look like — but Roy is childlike from start to finish. He starts by playing with trains, and ends walking on a spaceship surrounded by miniature alien life forms. (Ironic, then, that Spielberg's take on Peter Pan, the 1991 epic Hook, is one of his most treacly projects, far from the complexity of Close Encounters.)

This Means Something

Watching Close Encounters for the first time in years, finally on a big screen, I was taken by how that complexity does feel like subtext, if it's meant to be there at all. Both Roy and Jillian have been touched in a sense — the random sunburn that appears on their bodies because the spacecrafts shined lights in their faces while passing by, for example. Both are left with visions of Devils Tower that manifest in artistic fashion.

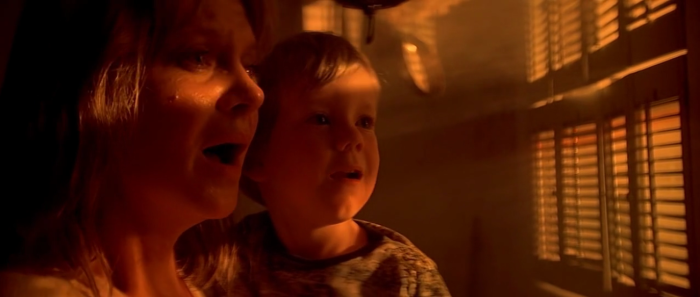

Jillian has a more primal urge to get to Devils Tower, or so it would seem: her young son Barry has been abducted by the aliens for reasons unknown. Though we see Jillian after reporting the incident to the authorities — she seems reasonably shell-shocked throughout — her journey seems as much about satisfying her own curiosity as it is about collecting her son. She rarely seems bothered about having lost him, either temporarily or permanently, let alone distraught. Perhaps on an innate level, she knows he's fine or believes that he has to be, but even that requires a leap of faith the film never quite establishes. The scene where Barry is taken is a phenomenal setpiece and seems like something that wouldn't be out of place in Poltergeist; it's genuinely terrifying and excellently staged, which makes it much more fascinating and inexplicable that no one seems to treat the aliens as a threat. She reunites with Barry in the coda, in a sweet moment that's overshadowed by what happens to Roy.

Both Close Encounters of the Third Kind and AI have similarly determined protagonists; like Pinocchio, they will themselves into situations where they can get an answer, a transformative moment that will bring purpose to their lives. Roy keeps repeating that the vision of Devils Tower "means something. This is important." But he's saying so because it has to be, or otherwise, he's wasting his time. AI's robotic boy David (Haley Joel Osment) has to meet the Blue Fairy, has to be turned into a real boy, because then he would have a true meaning in life: to be genuinely loved by the woman he calls his mother.

Both films feature scenes of abandonment; Roy is technically abandoned by his wife and kids, but it's massively, intentionally uncomfortable to watch him push them away past the point of no return. AI smartly reframes a scene of abandonment from the perspective of the child. We barely know Roy's kids, except for a few brief shots that try to communicate how lost they are in understanding why Mom and Dad keep yelling at each other. AI places David and his mother (Frances O'Connor) in a forest as she tries to save him from death, and he breaks down emotionally because he can't fully grasp why she's leaving him.

Wish Fulfillment

If there's anything that has bothered me about Close Encounters and how it treats Roy, I was finally able to fully put my finger on this time around. It's not that Roy hates his family — he fails to prioritize them, as demonstrated when he tries to guilt them into seeing Pinocchio because it's what he wants. It's not that he leaves them — his wife leaves him, and it's hard to blame anyone for making that choice. It's that Roy is right to be obsessed. His determination pays off. He gets what he wants, and in no uncertain terms. Roy not only gets to see the descent of an alien ship into our world; he is chosen, almost literally handpicked, to join a crew to go onto said ship and do God knows what for an indeterminate, possibly infinite period of time.

I have no cockamamie theory to throw out here about how Roy is fantasizing this, or he's hallucinating, or he got knocked out with the gas that military planes dusted the surrounding area with. Within the framework of the film, he really gets to spend eternity with aliens. His visions did mean something, but they come at the expense of a family he'll likely never see again, and whose absence doesn't bother him. If the last hour felt as steeped in the messy and honest complexities of life as what precedes it, I might react differently. Instead, it's exuberantly staged and crafted wish fulfillment.

The Boy Grows Up

There's a lot of recognizable thematic work in Spielberg's later films. Darker fare like Minority Report introduces familial strife before eventually building to a happy ending. Father-son issues are common in the Spielberg films without a huge following, like The Terminal. The true anomaly in his career since he became a father is AI, a complex sci-fi spectacle that starts and ends bleakly. On its face, David finally gets what he wants: he speaks to an approximation of the Blue Fairy, and he gets to spend another day with his mother. But it's a clone of his mother, nothing close to the real, three-dimensional, spiky woman he unconditionally adored. And his "mother" is only around for a day, before her clone shuts down. The final shots of the film, as muted as the final shots of Close Encounters are bombastic and triumphant, suggest that David has come to grips with his isolated reality, and that his journey can only end when he shuts himself down.

Close Encounters of the Third Kind is one of the great spectacles of Steven Spielberg's career. For sheer technical wizardry, visual stylization, and wonderstruck setpieces, there are few films he's made that rival the 1977 film, whether you watch it on Blu-ray, DVD, or on the big screen. Its first two-thirds are thornier than a lot of the spectacles he would make in the years to come, even his overall best film, Raiders of the Lost Ark. It's complex and prickly in ways that go beyond John Williams' incredible score, the stunning cinematography, and Richard Dreyfuss' awestruck performance. (Dreyfuss' work does a lot to make Roy sympathetic even in unsympathetic moments.)

But I pause at its resolution; on its face, it's jaw-dropping filmmaking, but it validates a character whose remorse at leaving his family is absent. The complexity vanishes in favor of something more hopeful, almost inexplicably so. In the intervening years, Spielberg has gone back to the well of dark familial complexity just once, ending on a seemingly hopeful note. But the "privilege of youth" is gone from AI where it once resided in Close Encounters. The boy who made the 1977 film grew up, and the adult who made the 2001 film proves it.