HDTGM: A Conversation With Eric Red, Director Of 'Body Parts'

When the gang over at How Did This Get Made? gave me the heads up that we were covering Body Parts — a 1991 movie whose premise is as silly as it is strange — I was expecting something schlocky. And while the movie itself isn't my cup of tea (full disclosure: no horror film is), I was surprised to find a film that had such a unique voice. There's a craft to Body Parts, and a compelling, noir-ish sensibility.

I mention all this because it made me really eager to speak with the film's director, Eric Red; to find out what kind of a storyteller would make a movie like this.

With the help of Matt Mulcahey over at Deep Fried Movies, I was able to get in touch with Eric. He was super nice, but right off the bat he told me two things:

1. He only does interviews over email

2. He rarely does interviews about old films.

But he makes exceptions if the questions are interesting enough. So I tried my luck, made the cut, and boy was it worth it.

Below is a copy of our interview...

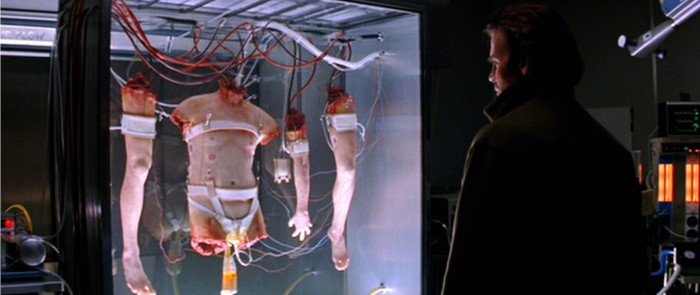

Synopsis: After a near-fatal car accident, criminal psychologist Bill Chrushank (Jeff Fahey) undergoes an experimental transplant surgery that provides him with a healthy new arm. But just when his life appears to be getting back on track, Bill learns that his "healthy new arm" previously belonged to a notorious serial killer; a revelation that causes great concern when Bill begins to inadvertently start fantasizing about murder.Tagline: A Medical Miracle has Become a Murderous Nightmare.

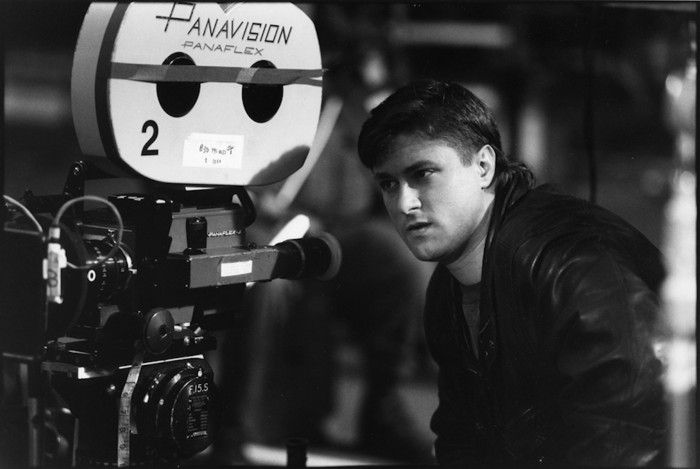

Part 1: Finding the Magic on Playgrounds Big and Small

Blake J. Harris: With a career that spans several decades and many cherished films, I have so many questions for you. But I can't help but begin by asking about a comment you made when we first connected. A comment that got me really excited for this interview. You said that Body Parts was the "most fun I ever had making a flick." That's great. I want to hear more! How did Body Parts earn that haloed superlative?Eric Red: For me, the fun was being able to make a grand scale major studio horror movie with all the resources to do it right: A story that was dream of mine to film. A great cast. Top crew. World-class special makeup effects. Major car chase and stunt gags. Fifty locations. 45 shooting days. Being able to film in anamorphic 35 MM. Every kind of special camera equipment available at the time. A full-scale symphonic acoustic score we recorded in Munich, Germany with a 105-piece orchestra.Blake J. Harris: Really? That's great.Eric Red: I became DGA on the show. Besides the terrific actors Jeff Fahey, Brad Dourif, Lindsay Duncan and Kim Delaney, I had a great producer in Frank Mancuso Jr. a sensational DP in Theo Van De Sande, a fearless and skilled stunt co-ordinator in Steve Boyum, a crack production designer with Bill Brodie, a kinetic editor with Anthony Redman and a dazzling composer with Loek Dikker—it was just a great team of collaborators who enabled me to make the film I wanted to make at a dream level. The actual filming was enthralling and fun, and the picture was a wonderful adventure and journey for everyone involved. Also, I was still a kid in my twenties when I made the flick, so it was like being in the biggest playground with all the toys. Never had as much fun making a movie before or since, and think the sense of fun we all shared filming it comes across in the movie to viewers.Blake J. Harris: Before we chat more about Body Parts, I'd love to hear a bit about your background and what led you to writing and directing. Was filmmaking always a passion of yours or was it something that you discovered as you got older? Eric Red: I always loved movies, especially horror, science fiction, and action movies. Like a lot of kids then, I started making 8MM and Super 8 MM films at about age seven, vampire movies and stop motion animation films and such. It's amazing how young you can be and naturally pick up the techniques of filmmaking and experience the magic when you just pick up a camera.Blake J. Harris: Where did you grow up, by the way?Eric Red: In New York City. There used to be a place called Young Filmmakers in Greenwich Village where kids could go and make films for free with equipment they had there, and many of my friends used that opportunity to make films. After high school, I had an inheritance so decided to try to make a feature, an action movie sent in Coney Island based on a story I read in Playboy that I optioned. So I holed up in an Asbury Park hotel for a week and wrote the script, then spent a year trying to raise the money. Surprise: that didn't happen.Blake J. Harris: Ha. Yeah, raising money is not easy.

Eric Red: I always loved movies, especially horror, science fiction, and action movies. Like a lot of kids then, I started making 8MM and Super 8 MM films at about age seven, vampire movies and stop motion animation films and such. It's amazing how young you can be and naturally pick up the techniques of filmmaking and experience the magic when you just pick up a camera.Blake J. Harris: Where did you grow up, by the way?Eric Red: In New York City. There used to be a place called Young Filmmakers in Greenwich Village where kids could go and make films for free with equipment they had there, and many of my friends used that opportunity to make films. After high school, I had an inheritance so decided to try to make a feature, an action movie sent in Coney Island based on a story I read in Playboy that I optioned. So I holed up in an Asbury Park hotel for a week and wrote the script, then spent a year trying to raise the money. Surprise: that didn't happen.Blake J. Harris: Ha. Yeah, raising money is not easy. Eric Red: So I did what filmmakers do and got pragmatic. Looked at the money I had left and realized I could make a top-of-the-line 16MM short film with all the fun stuff like action, stunts and special effects. That moment of realization I could actually make a movie happen felt incredibly empowering. I wrote the script in three days, and put the production together quickly with my producing partner Steve Bull using the NABET crew I'd assembled for the feature. The short was filmed in a bar in Hoboken, New Jersey. Gunmen's Blues was my film school.Blake J. Harris: I read online (so take that for what its worth!) that you "went broke trying to get national distribution for [Gunmen's Blues] and had to drive a cab in New York City for a year to recoup." Is that accurate?Eric Red: Gunmen's Blues did get national TV distribution on Night Flight, the rival network to MTV at the time, but I still went broke on the film and had to get a real job so drove a cab on the night shift in NYC for a year.Blake J. Harris: That's awesome. And, of course, as a current New Yorker I have to ask: What was that like? What was the city like back then?Eric Red: New York City was very different in the era of the late 70's and early 80s—it was more of a cultural melting pot, more colorful and vital, more dangerous (you had old Times Square where I watched all my formative movies) and a lot more exciting than it is now (in the opinion of someone who has been thirty years an Angelino).

Eric Red: So I did what filmmakers do and got pragmatic. Looked at the money I had left and realized I could make a top-of-the-line 16MM short film with all the fun stuff like action, stunts and special effects. That moment of realization I could actually make a movie happen felt incredibly empowering. I wrote the script in three days, and put the production together quickly with my producing partner Steve Bull using the NABET crew I'd assembled for the feature. The short was filmed in a bar in Hoboken, New Jersey. Gunmen's Blues was my film school.Blake J. Harris: I read online (so take that for what its worth!) that you "went broke trying to get national distribution for [Gunmen's Blues] and had to drive a cab in New York City for a year to recoup." Is that accurate?Eric Red: Gunmen's Blues did get national TV distribution on Night Flight, the rival network to MTV at the time, but I still went broke on the film and had to get a real job so drove a cab on the night shift in NYC for a year.Blake J. Harris: That's awesome. And, of course, as a current New Yorker I have to ask: What was that like? What was the city like back then?Eric Red: New York City was very different in the era of the late 70's and early 80s—it was more of a cultural melting pot, more colorful and vital, more dangerous (you had old Times Square where I watched all my formative movies) and a lot more exciting than it is now (in the opinion of someone who has been thirty years an Angelino). Blake J. Harris: Ha! And what was the job like? Driving a cab, I mean.Eric Red: You met all kinds of wild New Yorkers as a cab driver and heard some intense private conversations because a driver doesn't really exist for passengers. And it was a great way to pick up girls. I used to drive a Checker Cab, which don't think they have anymore but was a great car, a tank of a vehicle, which could handle the potholed streets. The thing that I loved best about driving a cab on the night shift was there is a time between two AM and four AM in the early morning that is a New York City most New Yorkers never see. There are no fares at that hour, no people or cars on the streets, just other cabs, street sweepers and garbage trucks and steam pouring out of wet streets left by the street washers like an urban jungle. New York was a city primeval during those hours, probably still is now. Not to wax poetic here, but it was a magical thing to experience. After a year though, I needed a change of pace so I went to Austin, Texas and wrote The Hitcher when I got there.Blake J. Harris: The Hitcher turned out to be a success. As did many of the other films you worked on in the 80s. Giving you, I assume, some degree of autonomy with regards to selecting projects. So I'm eager to how about how Body Parts came about. Was it an idea you'd been sitting on for a while?Eric Red: Around that time I became aware of the novel that Body Parts is adapted from, a book called Choice Cuts by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac. Two famous French thriller authors who wrote the novels that Vertigo and Diablolique were based on as well. I read Choice Cuts and was hooked by the central concept of an executed killer whose body parts are grafted in a medical experiment onto patients who have lost limbs, but the killer's body parts begin causing the deaths of the transplant recipients. It had a great twist at the end—(SPOILER ALERT)—that the killer's head was kept alive and he is having himself reassembled. It was a great high concept idea. I was excited as a director by the potential of mixing a psychological horror thriller with a gruesome horror action movie in a blend of the cerebral and visceral. So I started tracking down the rights only to discover the movie had a 25-year development history at various studios and even Alfred Hitchcock had tried to make it.

Blake J. Harris: Ha! And what was the job like? Driving a cab, I mean.Eric Red: You met all kinds of wild New Yorkers as a cab driver and heard some intense private conversations because a driver doesn't really exist for passengers. And it was a great way to pick up girls. I used to drive a Checker Cab, which don't think they have anymore but was a great car, a tank of a vehicle, which could handle the potholed streets. The thing that I loved best about driving a cab on the night shift was there is a time between two AM and four AM in the early morning that is a New York City most New Yorkers never see. There are no fares at that hour, no people or cars on the streets, just other cabs, street sweepers and garbage trucks and steam pouring out of wet streets left by the street washers like an urban jungle. New York was a city primeval during those hours, probably still is now. Not to wax poetic here, but it was a magical thing to experience. After a year though, I needed a change of pace so I went to Austin, Texas and wrote The Hitcher when I got there.Blake J. Harris: The Hitcher turned out to be a success. As did many of the other films you worked on in the 80s. Giving you, I assume, some degree of autonomy with regards to selecting projects. So I'm eager to how about how Body Parts came about. Was it an idea you'd been sitting on for a while?Eric Red: Around that time I became aware of the novel that Body Parts is adapted from, a book called Choice Cuts by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac. Two famous French thriller authors who wrote the novels that Vertigo and Diablolique were based on as well. I read Choice Cuts and was hooked by the central concept of an executed killer whose body parts are grafted in a medical experiment onto patients who have lost limbs, but the killer's body parts begin causing the deaths of the transplant recipients. It had a great twist at the end—(SPOILER ALERT)—that the killer's head was kept alive and he is having himself reassembled. It was a great high concept idea. I was excited as a director by the potential of mixing a psychological horror thriller with a gruesome horror action movie in a blend of the cerebral and visceral. So I started tracking down the rights only to discover the movie had a 25-year development history at various studios and even Alfred Hitchcock had tried to make it. Blake J. Harris: Even Hitchcock? Wow, interesting. So how did you go about trying to rescue the project from development hell?Eric Red: Just when it looked like extricating the rights was going to be impossible, I met Frank Mancuso Jr. Frank and his production company Hometown Films were based at Paramount Studios. As a producer, he was in a unique position at the studio because his father Frank Mancuso Sr. was chairman of Paramount. Frank had a deal where he could make four pictures a year, whatever movies he wanted, so he was completely autonomous. I pitched him Body Parts, Frank loved it, we went in to see the president of Paramount Sid Ganis and pitched it to him. Sid loved it and Body Parts was green lit in the room. Ten million budget. Start date six months away. We didn't even have a script yet. How often does that happen?

Blake J. Harris: Even Hitchcock? Wow, interesting. So how did you go about trying to rescue the project from development hell?Eric Red: Just when it looked like extricating the rights was going to be impossible, I met Frank Mancuso Jr. Frank and his production company Hometown Films were based at Paramount Studios. As a producer, he was in a unique position at the studio because his father Frank Mancuso Sr. was chairman of Paramount. Frank had a deal where he could make four pictures a year, whatever movies he wanted, so he was completely autonomous. I pitched him Body Parts, Frank loved it, we went in to see the president of Paramount Sid Ganis and pitched it to him. Sid loved it and Body Parts was green lit in the room. Ten million budget. Start date six months away. We didn't even have a script yet. How often does that happen?

Part 2: In Which the Parts All Come Together

Blake J. Harris: To your point, that kind of situation doesn't happen very often. Though generally for a good reason: that's a lot to do in a short amount of time. Tell me about how you guys put things together so quickly.Eric Red: Frank's company had an informal, fraternity atmosphere where we'd walk into each other's offices and toss around ideas. Frank loved filmmakers and loved taking risks, which was an inspiring environment he created as a producer that brought out the best in everyone, including me.Blake J. Harris: Nice.Eric Red: I wrote the first draft of the script, but was busy in pre-production directing the movie so we hired two additional writers, Norman Snider who wrote Dead Ringers, and Larry Gross who wrote 48 Hours, to do the shooting drafts. The biggest problem with the book in turning it into a film—and the reason that they hadn't been able to get a decent script in 25 years of development—was a problem of POV. The book was about a detective investigating the deaths of the transplant patients and solving the mystery, so he was outside the story. I believed that the main character needed to be one of the transplant patients who receives a limb from the killer then suffers the personality changes and begins to investigate what's going on, so the audience experiences the mystery and horror first person through his eyes. Also, in the novel Choice Cuts the big twist—(SPOILER ALERT)—that the killer's head has been transplanted and he is being reassembled is the last chapter, and he's just a body on an operating table. It seemed obvious in a movie that the whole last act had to be the killer out on the street ripping his parts off the transplant recipients in slasher movie fashion so the movie would escalate from psychological thriller into full-on horror action mode. Blake J. Harris: That makes sense.Eric Red: Frank agreed with all this. The biggest contribution I made in my drafts of the screenplay to Body Parts was structuring all that stuff out and designing the action sequences. Norman and Larry made huge contributions fleshing out the characters and writing the dialogue. Ironically, The Writer's Guild credit arbitration for Body Parts was one of the largest in the guild's history with something like twenty screenwriters who had written scripts over two decades fighting for credit, including Robert Benton. Ultimately the WGA awarded myself and Norman shared screenplay credit. I felt Larry Gross should have been credited as well and wrote a letter to the guild, but unfortunately Larry didn't receive screen credit.[Note: We interviewed Larry Gross last year to talk about writing Streets of Fire]Eric Red: We decided on Toronto to film the movie because the city had the look we needed and started shooting in December of 1989. In my wildest dreams, never imagined I'd be able to make Body Parts on a major studio level with that budget and those resources, and tried to make the most of it.Blake J. Harris: Tell me a bit about the lead, Jeff Fahey. How was he cast?Eric Red: We had no idea who we were going to cast as Bill, because for obvious reasons many leading men shied away from playing a guy with a transplanted arm even though this was a studio movie. Fortunately, Paramount did not make any star requirements for the cast and just wanted good actors, so we had flexibility. One day, Jeff Fahey came in and interviewed with Frank and I, and we knew right away he was our guy. He had a very visceral vibe.

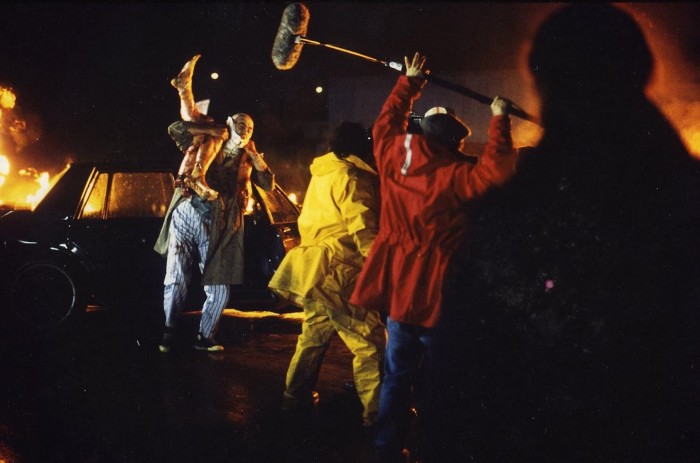

Blake J. Harris: That makes sense.Eric Red: Frank agreed with all this. The biggest contribution I made in my drafts of the screenplay to Body Parts was structuring all that stuff out and designing the action sequences. Norman and Larry made huge contributions fleshing out the characters and writing the dialogue. Ironically, The Writer's Guild credit arbitration for Body Parts was one of the largest in the guild's history with something like twenty screenwriters who had written scripts over two decades fighting for credit, including Robert Benton. Ultimately the WGA awarded myself and Norman shared screenplay credit. I felt Larry Gross should have been credited as well and wrote a letter to the guild, but unfortunately Larry didn't receive screen credit.[Note: We interviewed Larry Gross last year to talk about writing Streets of Fire]Eric Red: We decided on Toronto to film the movie because the city had the look we needed and started shooting in December of 1989. In my wildest dreams, never imagined I'd be able to make Body Parts on a major studio level with that budget and those resources, and tried to make the most of it.Blake J. Harris: Tell me a bit about the lead, Jeff Fahey. How was he cast?Eric Red: We had no idea who we were going to cast as Bill, because for obvious reasons many leading men shied away from playing a guy with a transplanted arm even though this was a studio movie. Fortunately, Paramount did not make any star requirements for the cast and just wanted good actors, so we had flexibility. One day, Jeff Fahey came in and interviewed with Frank and I, and we knew right away he was our guy. He had a very visceral vibe. Blake J. Harris: What was he like to work with? Were there any things you remember doing, as director, to help him get into the mind of "Bill Chrushank?"Eric Red: Jeff and I had a great time working together. As a man, Jeff has great personal warmth and terrific sense of humor, even though he projects edge as an actor. The biggest thing I did directorially was bring out the warm and personable side of the actor on screen, which wasn't hard because that's who he is. Jeff comes from a big Irish family of thirteen brothers, which is a very likeable part of his personality. Whenever possible, I encouraged his natural warmth in his performance, because the family side of Bill Chrushank is crucial, and when the arm starts changing him and Bill turns violent on his family that's where the horror comes in. If you know Jeff, you know Robert Rodriguez also captured that charismatic and personable side of him in Planet Terror, which I think besides Body Parts is one of Jeff's two best performances.Blake J. Harris: From a production/logistics standpoint, what were some of the hardest scenes to film?Eric Red: The hardest scene by far to plan and film was the handcuff car chase. It was all first unit and took two and a half nights to shoot. The sequence involves the killer Charley Fletcher in one car handcuffing himself to Bill in another car then trying to rip his arm off in a high-speed vehicular chase into oncoming traffic. There were over a hundred intricate and complicated set ups required to get all the dynamic coverage of the car chase so I completely storyboarded it in advance. Filming involved plenty of inter-coordinated car stunt work with very some tricky camera placements. We used cars hooked together with camera rigs on back, we shot off insert cars, had cameras on bumper mounts, side mounts, you name it—we used precision stunt drivers for many of the shots and used Jeff and the other actors in cars on tow rigs for some shots.Blake J. Harris: Oh jeez.Eric Red: We were very safe, because the sequence was very well planned and rehearsed, but you're still dealing with complex and dangerous vehicular stunts around lots of crew and big equipment so we had to be careful and follow correct safety procedures staging it, which we damn well did. Needed to light a mile of freeway underpass because it was all night work. Plus it was freezing—we were shooting on Lakeshore Drive in Toronto in the dead of winter and riding on the back of insert cars going 50 MPH in 30 degree below zero weather with the wind chill factor, so it was a grueling sequence to film. It's one of the movie's highlights though.

Blake J. Harris: What was he like to work with? Were there any things you remember doing, as director, to help him get into the mind of "Bill Chrushank?"Eric Red: Jeff and I had a great time working together. As a man, Jeff has great personal warmth and terrific sense of humor, even though he projects edge as an actor. The biggest thing I did directorially was bring out the warm and personable side of the actor on screen, which wasn't hard because that's who he is. Jeff comes from a big Irish family of thirteen brothers, which is a very likeable part of his personality. Whenever possible, I encouraged his natural warmth in his performance, because the family side of Bill Chrushank is crucial, and when the arm starts changing him and Bill turns violent on his family that's where the horror comes in. If you know Jeff, you know Robert Rodriguez also captured that charismatic and personable side of him in Planet Terror, which I think besides Body Parts is one of Jeff's two best performances.Blake J. Harris: From a production/logistics standpoint, what were some of the hardest scenes to film?Eric Red: The hardest scene by far to plan and film was the handcuff car chase. It was all first unit and took two and a half nights to shoot. The sequence involves the killer Charley Fletcher in one car handcuffing himself to Bill in another car then trying to rip his arm off in a high-speed vehicular chase into oncoming traffic. There were over a hundred intricate and complicated set ups required to get all the dynamic coverage of the car chase so I completely storyboarded it in advance. Filming involved plenty of inter-coordinated car stunt work with very some tricky camera placements. We used cars hooked together with camera rigs on back, we shot off insert cars, had cameras on bumper mounts, side mounts, you name it—we used precision stunt drivers for many of the shots and used Jeff and the other actors in cars on tow rigs for some shots.Blake J. Harris: Oh jeez.Eric Red: We were very safe, because the sequence was very well planned and rehearsed, but you're still dealing with complex and dangerous vehicular stunts around lots of crew and big equipment so we had to be careful and follow correct safety procedures staging it, which we damn well did. Needed to light a mile of freeway underpass because it was all night work. Plus it was freezing—we were shooting on Lakeshore Drive in Toronto in the dead of winter and riding on the back of insert cars going 50 MPH in 30 degree below zero weather with the wind chill factor, so it was a grueling sequence to film. It's one of the movie's highlights though. Blake J. Harris: As for the body parts themselves: were they trying to "get back" to their body, or were they merely inflicting machinations on those who received transplants?Eric Red: The bigger question is really whether the transplant recipients' own traumatic psychological issues with losing their limbs and getting grafted new ones are responsible for the scary things happening to them, or if the new limbs really have a mind of their own. That's the mystery of the movie. But I'm not telling. Let the viewers have the fun of figuring it out!Blake J. Harris: [laughs] That's fair. I appreciate a good mystery. But maybe you can tell me this instead: is the doctor his mother?Eric Red: Interesting question—not the biological mother certainly, but perhaps an emotional one. If you mean Bill, it would be very weird if the doctor were his mother since Lindsay Duncan injected an erotic element into Dr. Webb, where beneath her British reserve she gets a sexual charge out of cutting people up and reassembling them. Note that subtle lip smacking expression she gets when Jeff's bandages comes off and she sees the grafted arm on him the first time. But since the doctor must regard Charley Fletcher a bit like her child, one could call that strange gothic look on her face maternal when she walks up to Charley when he's holding his legs near the end. In a way, both Charley and Bill are the doctor's creations, so arguably she carries maternal feelings towards both of them. We should ask Lindsay Duncan!

Blake J. Harris: As for the body parts themselves: were they trying to "get back" to their body, or were they merely inflicting machinations on those who received transplants?Eric Red: The bigger question is really whether the transplant recipients' own traumatic psychological issues with losing their limbs and getting grafted new ones are responsible for the scary things happening to them, or if the new limbs really have a mind of their own. That's the mystery of the movie. But I'm not telling. Let the viewers have the fun of figuring it out!Blake J. Harris: [laughs] That's fair. I appreciate a good mystery. But maybe you can tell me this instead: is the doctor his mother?Eric Red: Interesting question—not the biological mother certainly, but perhaps an emotional one. If you mean Bill, it would be very weird if the doctor were his mother since Lindsay Duncan injected an erotic element into Dr. Webb, where beneath her British reserve she gets a sexual charge out of cutting people up and reassembling them. Note that subtle lip smacking expression she gets when Jeff's bandages comes off and she sees the grafted arm on him the first time. But since the doctor must regard Charley Fletcher a bit like her child, one could call that strange gothic look on her face maternal when she walks up to Charley when he's holding his legs near the end. In a way, both Charley and Bill are the doctor's creations, so arguably she carries maternal feelings towards both of them. We should ask Lindsay Duncan! Blake J. Harris: Perhaps there will be a Part 2 of our Body Parts investigation? But until then...just a few more questions. I want to talk a bit about the release. Body Parts came out in August 1991. This was just weeks after the arrest of Jeffrey Dahmer (who had been found to have a collection of dismembered body parts). Did that have any impact on the film's release?Eric Red: Unfortunately, yes. Dahmer was all over the news, but that didn't affect Body Parts until some genius in Paramount marketing removed the ads for the movie in Milwaukee where the serial killer was apprehended. Next day, the front page of the LA times read, "Paramount Pulls Body Parts Ads In Milwaukee." Of course, this created a totally erroneous and undeserved association in the public mind between our movie and Jeffrey Dahmer; one that didn't exist before Paramount yanked the ads, and hurt us at the box office.Blake J. Harris: Oh man, that's terrible.Eric Red: God bless Howard Stern who defended our movie on his show. When somebody called in saying Paramount should close the film, Stern said on air, "You idiot, the movie was called Body Parts and made a year before Dahmer, and doesn't have anything to do with Dahmer, so have a Coke and a Smile and shut the f- up!"

Blake J. Harris: Perhaps there will be a Part 2 of our Body Parts investigation? But until then...just a few more questions. I want to talk a bit about the release. Body Parts came out in August 1991. This was just weeks after the arrest of Jeffrey Dahmer (who had been found to have a collection of dismembered body parts). Did that have any impact on the film's release?Eric Red: Unfortunately, yes. Dahmer was all over the news, but that didn't affect Body Parts until some genius in Paramount marketing removed the ads for the movie in Milwaukee where the serial killer was apprehended. Next day, the front page of the LA times read, "Paramount Pulls Body Parts Ads In Milwaukee." Of course, this created a totally erroneous and undeserved association in the public mind between our movie and Jeffrey Dahmer; one that didn't exist before Paramount yanked the ads, and hurt us at the box office.Blake J. Harris: Oh man, that's terrible.Eric Red: God bless Howard Stern who defended our movie on his show. When somebody called in saying Paramount should close the film, Stern said on air, "You idiot, the movie was called Body Parts and made a year before Dahmer, and doesn't have anything to do with Dahmer, so have a Coke and a Smile and shut the f- up!" Blake J. Harris: That's great. Though obviously some damage had already been done. What was the release like? How did the movie do?Eric Red: Body Parts had a pretty good opening weekend but wasn't a hit, which it maybe could have been based on how well audiences were reacting. Perhaps it would have been different if we had kept the title Choice Cuts. Frank wanted a different title than Body Parts but I fought for that title—maybe ultimately to the movie's disadvantage.Blake J. Harris: Maybe...Eric Red: [But] audiences loved it, when they went. It played for audiences like I hoped it would. Can't complain about the distribution, either. Body Parts got a major theatrical release and Paramount opened it in about 2,200 theaters with a pretty decent P&A commitment on TV and newspaper ads. It was a respectable release and we did good opening weekend business. I felt the film would have done much better at the box office if we hadn't been subject to that awful timing and if Paramount hadn't gotten gun-shy in the marketing afterwards. There are a lot of things a director controls making a movie but timing is not one of them—that's out of your hands. I was nominated for a Saturn Award as director and Loek Dikker won a Saturn as composer. It got a lot of great reviews in papers like the L.A. Times and The Boston Globe, who did a major article on it, which was all very nice.

Blake J. Harris: That's great. Though obviously some damage had already been done. What was the release like? How did the movie do?Eric Red: Body Parts had a pretty good opening weekend but wasn't a hit, which it maybe could have been based on how well audiences were reacting. Perhaps it would have been different if we had kept the title Choice Cuts. Frank wanted a different title than Body Parts but I fought for that title—maybe ultimately to the movie's disadvantage.Blake J. Harris: Maybe...Eric Red: [But] audiences loved it, when they went. It played for audiences like I hoped it would. Can't complain about the distribution, either. Body Parts got a major theatrical release and Paramount opened it in about 2,200 theaters with a pretty decent P&A commitment on TV and newspaper ads. It was a respectable release and we did good opening weekend business. I felt the film would have done much better at the box office if we hadn't been subject to that awful timing and if Paramount hadn't gotten gun-shy in the marketing afterwards. There are a lot of things a director controls making a movie but timing is not one of them—that's out of your hands. I was nominated for a Saturn Award as director and Loek Dikker won a Saturn as composer. It got a lot of great reviews in papers like the L.A. Times and The Boston Globe, who did a major article on it, which was all very nice. Blake J. Harris: That's good to hear. And the film certainly found its audience over the years...Eric Red: It seems like the flick has been receiving more attention lately than it did when it came out. Recently Robert Rodriguez texted me about how much he loved the movie and that he saw it in the theater in Texas eight times when it came out, which made my day. I think a lot of the great action directors who were teens when the flick came out respond to Body Parts because the visuals are so aggressively kinetic, which is more how films are shot now then they were then.Blake J. Harris: Of all the reactions—both then and now—do you have a favorite? Does any particular one stand out?Eric Red: My favorite reaction is easy: Body Parts is the only movie I've made where the whole audience applauds and cheers over the end credits because they enjoyed the movie so much. Not kidding. Audiences did in 1990 at the Grauman's Chinese in Hollywood at every showing I attended. A few years ago, Cinefamily screened the 35 print in a theater on Fairfax with an audience who was mostly in their thirties and hadn't seen the film before. At the end credits, they all applauded and cheered. Twenty-five years between screenings, it got same reaction, so it seems the flick has stood the test of time.

Blake J. Harris: That's good to hear. And the film certainly found its audience over the years...Eric Red: It seems like the flick has been receiving more attention lately than it did when it came out. Recently Robert Rodriguez texted me about how much he loved the movie and that he saw it in the theater in Texas eight times when it came out, which made my day. I think a lot of the great action directors who were teens when the flick came out respond to Body Parts because the visuals are so aggressively kinetic, which is more how films are shot now then they were then.Blake J. Harris: Of all the reactions—both then and now—do you have a favorite? Does any particular one stand out?Eric Red: My favorite reaction is easy: Body Parts is the only movie I've made where the whole audience applauds and cheers over the end credits because they enjoyed the movie so much. Not kidding. Audiences did in 1990 at the Grauman's Chinese in Hollywood at every showing I attended. A few years ago, Cinefamily screened the 35 print in a theater on Fairfax with an audience who was mostly in their thirties and hadn't seen the film before. At the end credits, they all applauded and cheered. Twenty-five years between screenings, it got same reaction, so it seems the flick has stood the test of time.

Part 3: In Pursuit of the Million Dollar Question

Blake J. Harris: Speaking more broadly here: you've made a career out of scaring people. This is kind of an odd (or perhaps just poorly worded) question, but I was curious if, going into a film, that was an explicit objective or more a byproduct of the type of stories you like to tell? I especially ask since your work tends to focus on more of a slow-burn, psychological fear than, say, the jump-in-your-seat moments common in slasher/monster film.Eric Red: I like working in the thriller and horror genres, which deal in suspense and tension, because they are cinematic and exciting movies to make and those are the stories I'm naturally drawn to. But the human elements must be present. I always try to exploit the human level of the story and explore the psychological underpinnings of the characters, because that makes a thriller more convincing and involving. In Body Parts, the essential mystery is whether Jeff Fahey's personality is disintegrating because of the trauma of losing his arm and getting someone else's, or if it's serial killer's spirit in the flesh of the new arm that is changing Jeff's personality. In some ways, the most horrifying scene in the film is when he hits his son with the arm and has to leave home and his family, and he's cut off from those he loves and alone. This is the human stuff that makes a thriller or horror movie really work on an audience, not just splattering a lot of blood and gore around.Blake J. Harris: Right. Eric Red: There's a scene in Body Parts where Jeff goes back to Lindsay's office and confronts her telling her he wants the arm off. In writing the script, I thought the character would feel the arm was alien, not part of himself, and would want it removed. Ten years after we made Body Parts, surgeons in France successfully grafted someone else's hand onto another man's body after that guy had lost his own hand. Six months later, the patient came back to the doctors and demanded they remove the hand. He said it felt like it wasn't his and somebody else was invading his body. Life imitates art.Blake J. Harris: Funny how that happens, isn't it?Eric Red: My most recent film 100 Feet was about a woman under house arrest haunted by the ghost of husband she killed in self-defense. It had only one kill in the whole film. Almost the entire movie is Famke Janssen alone in a house with a ghost. What interested me in writing the script and directing the film was doing an exercise in tension and suspense without relying on blood and gore, just manipulating audience expectations—just when you think something terrible is about to happen, it doesn't, and just when you least expect it, it does. And when that single extremely gruesome kill does come it's a doozy, because there's nothing in the movie up to that point that leads you to expect it. That's the kind of stuff I enjoy as a director.Blake J. Harris: Last question...and taking us full circle a bit. You've been telling creepy, unsettling stories for several decades now. What have you learned about the nature of fear? And, in your opinion, why the hell do we—as humans, as filmgoers!—pay money to be creeped out and unsettled?!?!Eric Red: That's the million-dollar question, isn't it? I suppose that for most people it's fun to be scared in a safe way like a movie, and ultimately horror movies are a thrill ride like a roller coaster. But Alfred Hitchcock put it best when he basically said that the intrinsic importance of pure shock value is it jolts the audience out of their rational complacency and intellectual considerations to a pure emotional place where they feel on a primal human level. That's almost profound.

Eric Red: There's a scene in Body Parts where Jeff goes back to Lindsay's office and confronts her telling her he wants the arm off. In writing the script, I thought the character would feel the arm was alien, not part of himself, and would want it removed. Ten years after we made Body Parts, surgeons in France successfully grafted someone else's hand onto another man's body after that guy had lost his own hand. Six months later, the patient came back to the doctors and demanded they remove the hand. He said it felt like it wasn't his and somebody else was invading his body. Life imitates art.Blake J. Harris: Funny how that happens, isn't it?Eric Red: My most recent film 100 Feet was about a woman under house arrest haunted by the ghost of husband she killed in self-defense. It had only one kill in the whole film. Almost the entire movie is Famke Janssen alone in a house with a ghost. What interested me in writing the script and directing the film was doing an exercise in tension and suspense without relying on blood and gore, just manipulating audience expectations—just when you think something terrible is about to happen, it doesn't, and just when you least expect it, it does. And when that single extremely gruesome kill does come it's a doozy, because there's nothing in the movie up to that point that leads you to expect it. That's the kind of stuff I enjoy as a director.Blake J. Harris: Last question...and taking us full circle a bit. You've been telling creepy, unsettling stories for several decades now. What have you learned about the nature of fear? And, in your opinion, why the hell do we—as humans, as filmgoers!—pay money to be creeped out and unsettled?!?!Eric Red: That's the million-dollar question, isn't it? I suppose that for most people it's fun to be scared in a safe way like a movie, and ultimately horror movies are a thrill ride like a roller coaster. But Alfred Hitchcock put it best when he basically said that the intrinsic importance of pure shock value is it jolts the audience out of their rational complacency and intellectual considerations to a pure emotional place where they feel on a primal human level. That's almost profound.