'Logan' Spoiler Review: No More Adamantium Claws In The Valley

(In our Spoiler Reviews, we take a deep dive into a new release and get to the heart of what makes it tick...and every story point is up for discussion. In this entry: James Mangold's Logan.)

There has never been a superhero movie like Logan.

Paced like a '70s drama, styled like a classic western, and powered by characters rather than action, director James Mangold has concluded the saga of Hugh Jackman's Wolverine with a powerful pop rather than an empty bang. Like the very different Deadpool, this is a superhero movie, an X-Men movie, that is beholden only to itself. It has shrugged off its masters and is all the better for it.

And while most superhero movies dwell on surface pleasures, Logan offers meat to chew on. Bloody and bitter meat, but meat thoughtfully and carefully prepared. Let's take a deep dive into what makes Logan so special and so different.

Spoilers head, of course.

Snikts and Stones

Logan opens with a startling scene. Our hero, the man whose name is the title of the movie, the superhero we've seen save the world a few times in the past, awakens from a drunken slumber in the back of the limousine he now drives for a living. A group of men are stealing his hubcaps. He intervenes. They shoot him. He doesn't die, but it sure looks like it hurts.

In the fight that follows, Logan steps in front of gunfire to protect his car, which is a lease and his only source of income. He dispatches his attackers, but it's not easy. If his superhuman healing abilities( fading but still kicking) weren't active, he'd be a dead man a half dozen times over. It's unlike any other scene in a comic book movie – it's a sequence devoid of excitement or romance. Logan retreats to a gas station restroom to clean himself up and painfully waits while his body ejects the bullets that once wouldn't have fazed him in the slightest. Time has caught up with the warrior. The ageless Wolverine has gotten old.

Everyone and everything is dying in Logan. The world as we know it is fading, giving way to a future that is realistically depressing and mundanely dystopic. Our hero has seen his greatest strength, the adamantium skeleton installed within his body decades earlier, turn against him, poisoning him and undoing his ability to shrug off any wound. It's easy to think of soldiers, of war heroes, who return from battle and slowly realize that every single thing they were trained to do well doesn't apply to the real world. The very things that made them powerful, that made them useful, drive them to self-destruction. Logan's lack of self care is a delayed suicide attempt.

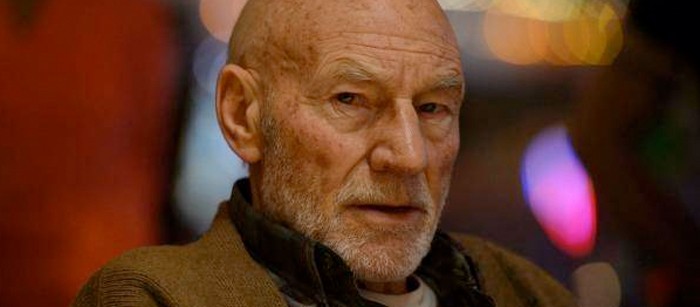

Professor Charles Xavier, once the most powerful mind in the world and the respected leader of a school built for the betterment of mutantkind, battles an unspecified illness that has rendered him unpredictable. In one of the film's most disquieting moments, the man once called Professor X fights back tears and apologizes to a room full of strangers after one of his seizures, brought on because he didn't take his medication, nearly killed them with its uncontrollable blast of psychic energy. My grandfather was an engineer whose work was used in NASA's space shuttle. His final descent into dementia was almost impossible to endure. Watching Charles Xavier battle his own mind, the way tiny shred of himself appear amidst the anger and confusion, is heartbreaking. And familiar.

Those superpowers, the abilities that made Logan and Charles so confident and so primed to fight on behalf of the world, have revealed their double edged nature. A brilliant mind is undone by dementia. A skilled soldier is undone by age. The things we take for granted, the things that define our youths, slip away. Our finest assets turn against us. Time is the great enemy of humanity. It turns out that it's the great enemy of superheroes, too.

In the end, Logan and Charles have to stare an unforgiving world in the eye and dredge up all of the dignity they can muster for their final fight. They both die painfully, away from a public battlefield, in service of a battle they did not choose being fought on a scale where the stakes amount to a handful of souls. Logan brings its heroes down to our level – a fight to reclaim the self is a battle we all know. It's the battle we all have coming.

Stripped Down, Worn Out, Going Strong

The filmography of James Mangold defies easy and instant classification. At a glance, he appears to be a working director, a journeyman comfortable in all genres who can turn out strong work on any job. However, our obsession with auteurs blinds us to a filmmaker with a steady thematic through line.

Mangold makes movies about people (usually men) and the institutions, real or imaginary, that they fight to maintain. In Cop Land, he tells the story of a police officer battling corruption in his ranks. In the adorable Kate & Leopold, he builds a rom-com around a time-displaced man representing a type of gentleman that has vanished from the modern era. In 3:10 to Yuma, men living in the wild west risk life and limb to protect the vague concept of law and order. Even those films that don't fit this tidy description feel connected by invisible tethers. His Johnny Cash biopic Walk the Line is less about a legendary singer and more about how that singer struggled to find his place in a world that he would come to define.

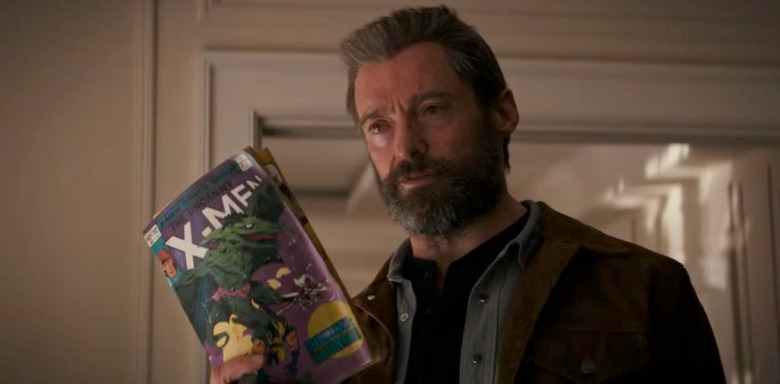

Logan is a movie about people who fight and die for a forgotten cause. When the film begins, the X-Men are gone, existing only in tattered comic books. But as that group's final two representatives, Logan and Charles must represent their team, their institution, one more time. What good is a set of ideals if you're not going to fight for them in the middle of the North Dakota woods in a brawl that will never be remembered? The unseen battles are what define us.

Mangold's adaptability as a filmmaker is something to be treasured. We take so much pleasure in dissecting the work of storytellers which instantly identifiable styles that we sometimes fail to appreciate directors who simply know where to put the camera. Mangold's stripped-down style, his straightforward depiction of weary men and women doing their damnedest, is to be treasured and respected.

The New American Wasteland

Logan was developed and shot long before Donald Trump was elected president of the United States, but like television's The Young Pope before it, the film can't help but feel like one of the first accidental responses to the current administration. Like the most powerful art, this movie has a political stance.

To be fair, the X-Men have always been political. These are the stories of a marginalized group, people who are different, people who face discrimination on the streets and in government legislation. The mutants fight not just to protect the planet, but to reverse prejudices. They are, like Superman before them, bleeding heart "social justice warriors." And as Logan begins, they have lost.

A wall runs along the Texas/Mexico border and the drunken frat boys riding in Logan's limo chant "USA!" as they drive by border patrol vehicles. Driverless trucks populate the highways, but instead of a hopeful future, they represent a world where blue collar employment is rapidly dwindling. It's no accident that Logan himself has found employment as a driver, a job that will soon be obsolete.

In a year where refugees are literally fleeing the United States and losing fingers to frostbite as they cross the Canadian border, the central plight of Logan becomes all the more immediate. Here are a group of young mutants, victims of a war they cannot control and only want to escape, fleeing a privatized military force across the new American wasteland. They are victims treated like criminals, children painted as monsters. It's disconcerting that Logan climaxes with these kids, these Mexican refugees, finding a safe haven north of the border. America is no home for mutants. America is no home for those who seek a better, safer life. Not in Logan. Not anymore.

Of course, Logan himself perishes helping these kids. The mission of the X-Men, that fight for justice, has always been depicted on a massive scale. But real change, the real nudges to social structure, occur in the shadows. We cannot save America or the world on our own, but a thousand good deeds from a thousand good people, working anonymously because it's the right thing to do, can tip the needle. There's still time. You're here right now. "Someone has come along," Charles tells Logan when a simple moment of everyday, mundane heroism reveals itself. He's right. We're here right now.

A Harsher World

Logan is the least exciting X-Men movie and that is, somehow, high praise. In a movie where superheroes can't start cars and old men forget their medicine and simple family dinners offer respite from an otherwise harsh existence, it should come as no surprise that violence isn't enticing or even fun. Yes, the Wolverine goes full berserker, but Mangold's camera doesn't shy away from what those claws do to other people...or what they do to the man wielding them.

Like Deadpool before it, Logan is the latest in a wave of R-rated superhero movies, but that restricted rating isn't an excuse to get bloody for the sake getting bloody. Rather, it offers the film the opportunity to dwell on what it means to take a life. This can be a cruel movie, but that harshness comes coupled with purpose. Somedays, it's fun to watch the Avengers bloodlessly defeat an army. On other days, it helps to be reminded that every life taken takes a toll.

At first, it's disconcerting to hear Logan and Charles say "fuck," almost as if we're watching different characters than the ones we've been following for 17 years. But this isn't a "grim and gritty" choice, profanity for the sake of profanity. Instead, it's the film stripping itself of that sanitized, superhero movie veneer. The candy shell of the PG-13 rating, the rating equivalent of three kids standing on each other's shoulders in a trench coat and pretending to be an adult, has melted away. What better way to sell a fallen world and its fallen heroes than rejecting the all-ages banner, the one that promises audiences that everything is going to be okay?

Because everything is not okay in Logan. And for the survivors of the film, everything will probably continue to not be okay. The fight is just beginning.

Go West, Old Mutant

It's no accident that Logan begins in Mexico and Texas, travels north to Oklahoma, and concludes in North Dakota. This stretch of land, with its unforgiving deserts, expansive farmland, and dense forests, is home to the American western. And this movie is very much a western.

It certainly helps that Hugh Jackman, who looked like a young Clint Eastwood when he was originally cast as Wolverine, continues to give off similar vibes 17 years later. There's certainly a small dash of The Outlaw Josey Wales in his performance here – the stoic, hardened soldier still fighting for a lost cause. Mangold knows this and places his leading man against the proper backdrops and iconography. The bad boy outlaw, the killer who used to keep other killers awake at night, lurches out of hiding in the Mexican desert so he can go on one last ride.

And this future America, this unsettling 2029, has reverted back to the wild west in a number of ways. Take the extended sequence where Logan, Charles, and mutant refugee Laura stop at a farmhouse, only to learn that the family who lives there is being preyed upon by the larger farms nearby. They turn off their water, harassing them in an attempt to force them to move on. This war of intimidation, the big rancher versus small farmer dynamic, is common in films set in 19th century America. To see it play out here, with Logan even rising to protect the family from aggressors, drives home the point of film. This isn't a western because Mangold likes westerns – Logan is a western because this world has taken a step backwards, reverted into a place where justice is more fleeting, where it has to be fought for rather than accepted as a given.

Shades of Sam Peckinpah

While Logan actively quotes one famous western in particular (more on that in a moment), the tone of the film recalls a very different filmmaker. With its unforgiving characters, chilling nihilism, and its focus on the harsh consequences of violence, the film evokes the work of director Sam Peckinpah.

Peckinpah's 1969 classic The Wild Bunch takes place in a transitional period – the 20th century has arrived, the old west is dying out, and the walls are closing in on the aging outlaws who called the formerly lawless Texas landscape home. Logan shares a similar point-of-view, taking these formerly romantic archetypes and reducing them to fading killers whose time at the top of the food chain has come to an end. In many ways, Logan is the reflection of The Wild Bunch: it's set in a transitional period where civilization is reverting to the wild west, where an ultimately noble character finds himself unable to adapt to exist in this harsh new reality. While both movies have different intentions in the end, you can feel Peckinpah's DNA buried deep within Mangold's work. They share the same brutal, remorseful heartbeat.

At the time of its release, The Wild Bunch was the most violent Hollywood western ever made, a film that lingered on every gunshot and spilled blood without remorse. If comic book movies are the new western (as many have argued), what does this say for Logan, which also takes a popular, mainstream genre and tells a story that doesn't spare us from the consequences of violence?

But Logan also recalls another Peckinpah masterpiece, albeit one less well-known. 1974's Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia was reviled upon release, but the decades have been kind to it. In that film, the great Warren Oates plays a retired American soldier living in Mexico, getting by on a diet of booze and self-loathing. When a crime boss demands the literal head of the title character and offers a $1 million reward, he sets out of a blood-soaked road trip to get the job done. Lots of people die. It doesn't go well.

These two brutal, hard-hitting neo-westerns about broken men going on one last desperate mission feel like natural companions. Both films center on shattered protagonists whose greatest strength (a penchant for violence) has become their greatest weakness (it is all they know). Both films put their leads through the emotional and physical wringer, tearing them to pieces (often literally). Both films showcase a nihilistic streak – the world is a shithole full of monsters and the only escape is booze and money (to buy a boat, in Logan's case). When Logan's genetically engineered clone murders an entire family in their home and stabs an unaware and unprepared Charles Xavier in the chest, Mangold reveals the same take-no-prisoners cruelty that defines the wild west of Sam Peckinpah.

Ultimately, Mangold is a more hopeful filmmaker than Peckinpah, offering genuine redemption for his characters. The leads of The Wild Bunch and Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia go down spitting and shooting and swearing. Logan allows its title character to die knowing that his daughter is safe. Mangold sees the light at the end of the tunnel.

Shane and the Guns in the Valley

While Logan ultimately feels akin to the work of Sam Peckinpah, another western actually figures into the plot of the film. During their stay in Oklahoma City, Charles and Laura find George Stevens' Shane on the television and the two of them get swept up in the film. It sends Charles down a nostalgic trip. It informs Laura's final lines in the film.

Released in 1953, Shane tells the story of a gunfighter played by Alan Ladd who rides into a Wyoming community, gets involved with the locals (including a woman and her young son, Joey), and volunteers to battle a cattle baron using intimidation and violence to force the settlers off of their land. He succeeds, but he doesn't plant roots. Now that "there are no more guns in the valley," he's free to ride away, ignoring Joey's calls for him to come back.

There are several ways to interpret Logan's connection to Shane, much like how there are several ways to interpret Shane itself. In one reading, Ladd's gunslinger is a noble figure, a violent man who leaves the valley because there is no need for a killer in a community that wants to relish its newfound peace. In another, Shane isn't quite so innocent and his actions in the film reflect a pattern of behavior – he moves on because he wants to find another embattled community where he can continue to do what he does best.

Both readings can apply to Logan. Is Wolverine the noble hero, the guy who kills to protect those who cannot protect themselves? Or is he just a bruiser who is good at one thing, which means he has no place across the border, in the new (and hopefully peaceful) community Laura and the other mutant refugees intend to build? In either case, Logan shares another vital trait with Shane – while he's a mutant superhero with freaky claws, Ladd's gunslinger is an oddly dressed eccentric whose appearance invites titters from his enemies before he wipes them out. Both are non-traditional heroes, outsiders who are underestimated by those who oppose them.

But in the end, Logan and Shane are defined by what they leave behind. For both of them, that means children who wish they had more time with their newfound father (or father figure). For both of them, that means a group of innocents, safe, for now, from those who mean them harm. And most importantly, that means they both have to move on. Shane gets to live. Logan has to die. In either case, there is no room for weapons, whether they be adamantium claws or six-shooters, in the world they fought to build.

The Evolution of a Wolverine

Logan knows that we've been watching Hugh Jackman play Wolverine for 17 years and it leans on it. Jackman himself, clearly in love with a character he has defined for a generation of audiences, gives this performance everything he has. This combination of affection, won over numerous movies, and dedication, courtesy of an actor who doesn't know how to phone it in, gives Logan a soul, the beating heart in the middle of the violence and despair.

What a rare breed of actor Hugh Jackman is! A man with movie star good looks, but without vanity. An actor unashamed to embrace the absurd, treating a mutant with metal claws with respect. An impressive physical specimen who transforms his body to sell an innate, inhuman toughness. A skilled comedian who knows how to cut right through this character's serious side with brilliant reactions and deadpan line delivery. In Logan, Jackman found an outlet for all that makes him special. Pity whoever plays Wolverine next.

And admire just how slyly Logan weaponizes our nostalgia for this character. Note how the ultimate villain of the movie is literally Logan himself, a clone raised in captivity who was never given the opportunity to find a family or a cause. This digitally de-aged Logan looks enough like the man we met in that bar back in 2000's X-Men to inspire reflection. This is Wolverine without his noble qualities, without the influences that made a man from a monster. This is a Logan without humanity. This is a Logan with Hugh Jackman's face, but not his soul.

Logan sidesteps the X-Men franchise continuity (and rightfully so), but it's ultimately all about that long-gone team. The X-Men saved the world. But they also saved Logan. And Logan saves Laura. And to paraphrase the Quran, to save one life is to save all of mankind.

An Imaginary Story

Logan presents a definitive ending for Wolverine: he is mortally wounded while battling his greatest enemy (himself), dies in the presence of his daughter, and is buried by a young group of mutants who will hopefully carry on his mission. Hugh Jackman's time as the character is over. This Wolverine is done.

But Wolverine will be back. He's too valuable of a character, too popular, for 20th Century Fox to keep him off the screen for too long. They may give us a few years to treasure Jackman's work, to get used to a world without Wolverine, but he'll return eventually. That's just business.

That means that Logan is another disparate piece in the ever-confusing X-Men franchise continuity, but unlike so many of its brothers and sisters, it stands alone. It feels built to exist as a larger statement and as standalone tale. Even if it is "ignored" by future movies, even if (when) Wolverine gets rebooted and we get a new series of Logan adventures, it looms large. The film has made its point.

For a few decades, DC Comics would publish "imaginary stories," issues set outside of regular continuity that explored questions and concepts that could not be explored in a more defined and regimented universe. In 1985, writer Alan Moore and artist Curt Swan created Whatever happened to the Man of Tomorrow?, the "final" Superman story that provided the Man of Steel and his supporting cast with a definitive ending...even though Superman stories would continue to be told for the foreseeable future. As I watched Logan, I was reminded of how this comic opens, an introduction that I found enticing at first and profoundly moving later: "This is an imaginary story...aren't they all?"

In terms of universes and continuity, Logan might as well not exist. It's a conclusion in a genre that never concludes. But the film's greatest asset, its finest trick, is that it doesn't care about the future. It's only concerned about the here and the now. Leave the future to whoever comes next. Stay in the moment. Say goodbye to Logan and Professor X. You'll see them again, but that doesn't make their departure any less moving.

Logan is an imaginary story. Aren't they all?