Cardboard Cinema: 'Last Friday' Brings The '80s Slasher Movie To Your Table

Welcome to Cardboard Cinema, a monthly feature that explores the intersection between movies and tabletop gaming. This column is sponsored by Dragon's Lair Comics & Fantasy in Austin, Texas.

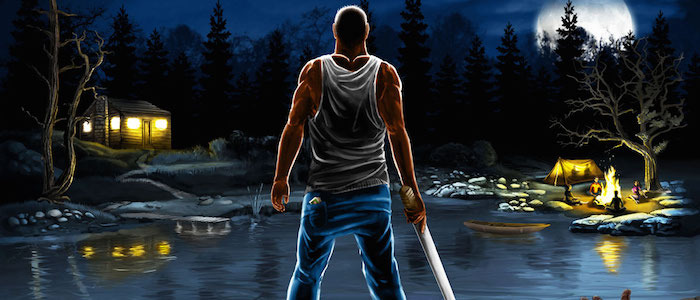

You know the scene: an isolated summer camp in an unspecified corner of the United States. You know the cast: a group of young camp counselors, all gathered for a summer of slacking off, getting stoned, and having sex. And you know the machete-wielding manic watching them from afar: he's going to kill them all.

Welcome to Last Friday, a board game designed by Antonio Ferrara and Sebastiano Fiorillo and published by Ares Games. This is a hidden movement deduction game, where one player moves in secret and works against the rest of the players, who move in full sight of everyone at table. And while this is familiar concept, there's a unique twist here: the player moving in secret wants to kill everyone else on the map.

Ki, Ki, Ki, Ma, Ma, Ma...

Last Friday is not a Friday the 13th game, per se. It's not a licensed adaptation or an official product attached to one of the most famous horror franchises of all time. But at the same time, it's totally a Friday the 13th game, borrowing that series' imagery, concept, and ideas and running with them. Some may roll their eyes and call it a rip-off, an attempt to cash in on something familiar. Yeah, it is...and thematically, it's perfect.

The slasher horror films of the '80s, in which masked and deranged killers stalked overly attractive twenty-somethings playing teenagers, were built on a foundation of theft. If one movie did something that worked or struck a chord with audiences, a completely different production would take those elements and run with them. You say rip-off, they'd say borrow. These days, filmmakers like to break out "homage" or "tribute" because it sounds fancier. To appreciate the slasher movie landscape, you have to learn to appreciate how these movies cannibalized each other, to appreciate the minor tweaks filmmakers would embed into their shameless copy and paste jobs. Last Friday's utilization of familiar imagery feels like a cheeky nod to the genre as a whole. Accuse it of being a Friday the 13th rip-off because it's about a vengeful killer stalking camp counselors, and imagine the creators shrugging and saying, "Hey, do you see any hockey masks? Is there anyone named Jason Voorhees? Totally original!" It's part of the charm.

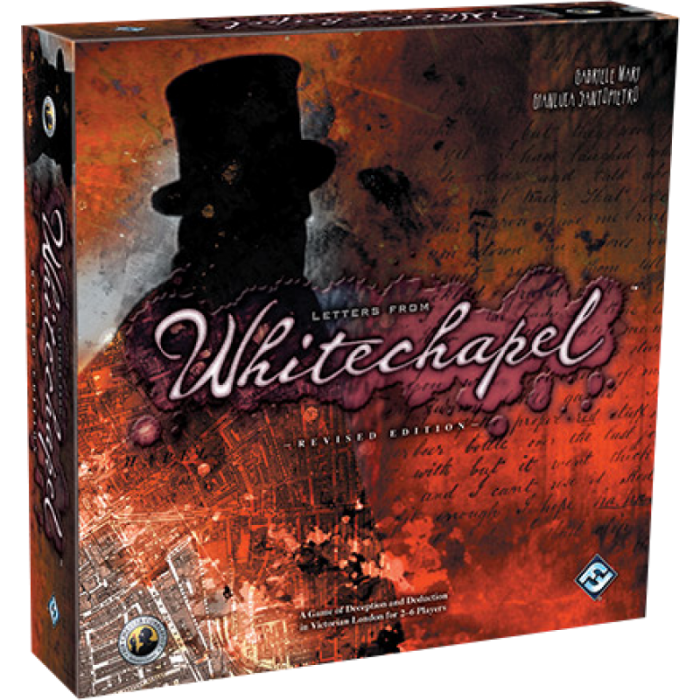

So it's even more appropriate that Last Friday, as an actual tabletop game, borrows pretty shamelessly from other board games. Specifically, it borrows its core mechanics from Letters From Whitechapel, a bonafide board game classic where players take on the role of police officers hunting down Jack the Ripper through 19th century London. Last Friday cleverly reverses that game's mechanics – instead of a team of players hunting down a killer, it's built on a system where the killer hunts down a team of players. In true '80s slasher movie rip-off mode, these minor tweaks barely mask the designers' blatant theft, as anyone who has played Letters From Whitechapel will take one look at Last Friday's board and instantly understand how to play much of the game.

And yet, this is an area where it's hard to even be remotely annoyed at Last Friday's blatant borrowing of familiar elements. Game design is all about iteration: a designer looks at what came before, takes what works, tweaks what doesn't, and evolves mechanics into something smoother and different (if not always different). Letters From Whitechapel itself is built on a foundation created by Scotland Yard, a perfected version of an otherwise adequate game system. It's in the spirit of board games and slasher cinema that Last Friday puts its hands in its pockets, whistles a little tune, takes from the best, and runs as fast as it possibly can.

The Rules of the Hunt

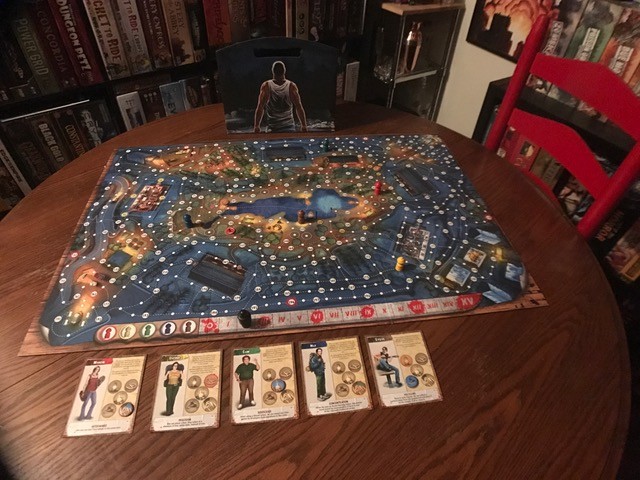

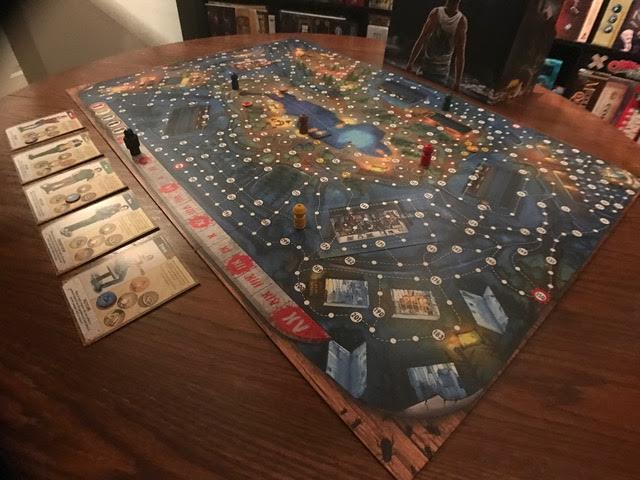

Last Friday's board depicts Camp Apache, a quaint summer camp in the middle of the wilderness where nothing could possibly go wrong. Except for the deranged maniac who has come back from the dead and plans to murder all of the camp counselors who have gathered this fateful night.

While the board looks complex at first glance, it's fairly simple to navigate after a brief explanation. One player takes on the role of the killer and they track their movement on a piece of paper behind a large screen, far from the eyes of his opponents/victims. Everyone else plays camp counselors, whose pawns actually sit on the board and move in full view of everyone at the table. The camp counselor players can move on small circles that form various paths around the board while the maniac player moves from one numbered space to another. Learning which routes are faster for each kind of player (and which choke points to utilize or avoid) is key. And yes, this is the exact movement mechanic introduced in Letters From Whitechapel, almost completely untouched.

Last Friday is played over four "chapters," which can also be tackled as individual sessions. In the first chapter, the camp counselor players need to find the keys to their cabins while the maniac stalks them, whittling their numbers down one-by-one. In chapter two, the counselors turn the tables on the maniac and attempt to hunt him and down and kill him for the events of the first chapter. In chapter three, the maniac is once again on the hunt, this time searching for the "predestined" player, a sort of "final girl" (or guy!) that he must kill in order to win the game. And in the final chapter, the predestined player must end things once and for all and kill the maniac who has been giving them so much trouble.

There are other important mechanics to know, like how the maniac player can kill a counselor by crossing over their space, removing an opponent from the board but also revealing to the table their approximate position, arming everyone else with precious information about their whereabouts. Both sides are armed with various special abilities – campers can plant lanterns to expose a stealthy maniac, leave bear traps lying around to slow his progress, and strap on running shoes to move a little faster. The maniac can use an axe to smash open the counselor's cabins, play a "plot twist" to take an extra turn, or use an "invisible" token to mysteriously vanish from sight. Much like Letters From Whitechapel (get used to hearing that a lot), knowing when to make use of your limited special abilities is key.

However, Last Friday does introduce one intriguing wrinkle to its borrowed core mechanics: depending on the chapter, the manic must reveal his current position or his position from a few turns ago every three moves. The "crap your pants" feeling of realizing that the maniac could literally be right next to you is unique and greases every panicky decision with palm sweat.

Last Friday is a Game With Heart

There are more rules to know in Last Friday (too many, in fact), but the chief appeal here isn't its recycled mechanics. It's the theme. There are plenty of horror-themed board games lining the shelves of friendly local game stores all over the world, but this is the rare tabletop experience to plunge you right into an '80s slasher movie. And unlike so many other horror games (slap Cthulhu any tired design and you're guaranteed to sell copies), this one was obviously crafted by designers and artists with love for the genre. The devil is in the details.

By playing the game over four chapters, Last Friday allows you to feel like you've just binged a movie and three of its sequels in one sitting, with each "movie" tweaking the formula of its predecessor. Camp counselors who survive part one and part two may die tragically (or heroically!) in part three or part four. The special abilities are perfectly tongue-in-cheek as well, riffing on tropes and cliches found strewn through '80s horror cinema and letting you weaponize them to play your best. I especially love how the maniac can trip up his prey by strategically killing his victims in key areas, leaving behind a corpse that cannot be passed unless another player has a shovel on hand and can bury it. I'm reminded of how so many horror movies find time for impromptu burials, complete with crosses made out of tree branches that someone managed to whip up in just a few minutes.

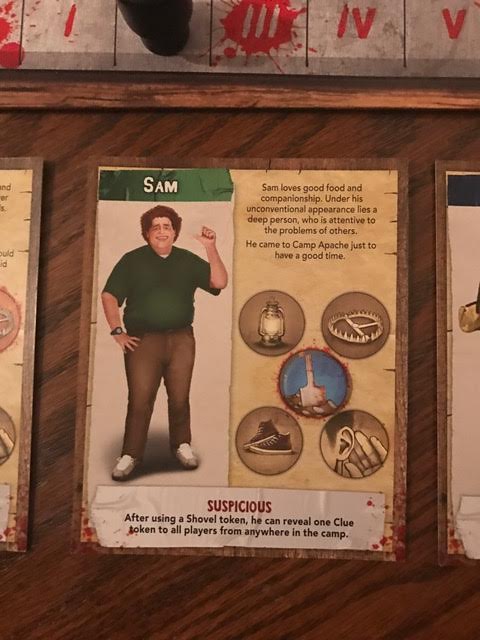

The counselors themselves also represent a collection of stock slasher movie characters, from the preppy jock to the naturalist hippie to the cool, bearded guy with the lumberjack style. There's even a pudgy, curly-haired nerd drawn to look like Shelly from Friday the 13th Part III. That's the kind of deep cut I can appreciate.

Like the actual game mechanics, much of Last Friday is borrowed from other sources, but everything has been borrowed by designers whose affection for both deduction games and '80s horror movies is worn right on the sleeve. This is a game with the absolute best intentions and a ton of heart, handcrafted for fellow horror nerds.

And It Looks (Mostly) Great

The attention to detail in the art goes beyond the fun character sheets and the character designs that instantly tell you everything you need to know about the character you're playing. The board itself is a joy to examine, filled with all kinds of small details and artistic touches. While the game asks you to focus on the numbers and pathways, take a moment to look beyond. Note that each area of the board is a fully realized thematic space. Recognizing this can transform a close encounter in the corner of the board into a desperate chase through a cemetery.

The components themselves mostly live up to the quality of the art on the board. The wooden pawns (whose design represent another theft from Letters From Whitechapel) look nice on the board and feel nice in the hand. The cardboard tokens, while a little small, get the job done. Unfortunately, the paper stock used for the cabins and the counselor reference sheets is cheaper than I'd like and both began to curl slightly the moment they were taken out of the box. It's especially egregious for the cabins, which spend most of the game sitting on the board. It's clearly a cost-saving measure, but making these out of cardboard (or at least thicker paper) would have gone a long way to making the game look just a little nicer on your table.

The nadir of the components is the maniac player's screen (behind which he tracks his hidden movement), which looks fine but suffers in execution. The reference map is too small and the reference charts vague enough to be both hilarious and infuriating. The most baffling aspect of it all is that the game requires you to bring your own paper, which wouldn't be a big deal if the screen didn't require a very specific size and shape in which to insert your paper. Prior to the game, I literally had to cut a piece of paper to match the space. A deal breaker? Nah. Super annoying? You betcha.

But a few subpar components don't matter if the game itself is fun and the design sound right? Correct. Unfortunately, for all of the nice things it has going for it, Last Friday isn't especially fun and its design is far from sound.

So Why Isn't Last Friday Any Good?

It brings me no pleasure to say that Last Friday's reach exceeds its grasp and that everything it tacks onto to the sound game system it has borrowed feels like just that – tacked on. The design has borrowed from something so elegant, simple, and lean and transformed it into a lumbering, confusing beast that frequently left even veteran gamers at my table feeling baffled and angry. If you are going to steal from the best, if you are going to iterate on what came before, you need to refine the old systems and whip them into shape. Last Friday just adds more stuff without taking care to note how the additional weight drags everything else down.

Let's start with the chapter format, which sounds cool on paper but falls flat in execution. While you could conceivably play each individual chapter as its own separate game, each of them feels too flimsy to stand on its own. Playing just chapter three without playing the first two chapters feels weightless and drama-free. But when you do play the full game and attempt all four chapters in order, the game fails to find a rhythm. Each chapter lasts 45 minutes to an hour, but that is never enough time to really sink your teeth into the scenario before the next chapter arrives and the rules completely change. Suddenly, everything you worked toward over the past hour has been wiped away and everyone starts from scratch.

Since Last Friday steals so much from Letters From Whitechapel, it demands to be directly compared to it. In that game, the Jack the Ripper player begins the game at his most powerful while the police players begin the game armed with almost no information whatsoever. However, with each passing round, the Jack player grows progressively weaker while the cop players learn more and more about his paths and where he may going. The balance shifts. The tension increases tenfold. It all culminates in a genuine battle of wits: how long can Jack evade an enemy who grows more powerful with every turn? It's dramatic. It's exciting. It's cinematic. It's satisfying.

By resetting the game and asking everyone to play by a completely new set of rules every 45 minutes or so, Last Friday cuts down any tension in its tracks. Suddenly, the hunter and the hunted alike have to get accustomed to the new rules and modify their strategy. It's always a little awkward and it usually involves everyone having to pause the game to ask what they're supposed to be doing in this chapter. Rather than allow everyone to get steadily better and more powerful, Last Friday interrupts your escalation and puts you back in square one.

But the most egregious choice may be the player elimination. Sure, a camp counselor player who gets cut down by the maniac can return to the game in the next chapter as a new character, but until then, all they can do is wait. And wait. Because if they get killed five minutes into a chapter, they're going to sit there twiddling their thumbs until everyone else wins or loses. Since the game encourages the maniac player to murder as quickly and effectively as possible (they are rewarded with more powers in future chapters by racking up a body count), this means that the manic player can best achieve their goals by making sure everyone else at the table isn't having fun. You win by killing other players, but killing other players means your friend having nothing to do for a long time. It's infuriating when you're a camp counselor and embarrassing when you're the maniac – you just ruined a friend's evening by playing the game as intended.

This could be solved by playing with fewer players and having each person take on two counselor characters, but the fun of deduction games comes from a team putting their heads together to solve a problem. You can do that, but where's the fun?

A Sample Round

I didn't finish my final game of Last Friday.

I was the maniac and five friends were the camp counselors. We were nearing the end of chapter three and I wasn't playing well. Not because I wasn't good at playing the maniac, but because I realized that playing conservatively was the only way for everyone else to have a good time. Instead of being a competitor, I was playing as a game master, trying to create interesting conflicts instead of trying to play the actual game as intended. Because if I did the latter, no one would be having a good time.

If I was actually playing as intended, I would have had to watch my friends not play the game as I chopped them down. And in chapter two, when the counselors came after me to avenge their fallen friends, I deliberately put myself in harm's way and ensured plenty of close calls because I realized that staying away from my pursuers for 15 rounds was going to be easy and boring, a combination that can kill any game night in its tracks. And in chapter three, where the campers gain the ability to push the maniac back a space by crossing his path, an opponent had trapped me in a corner, using the specific layout of the area to keep me at bay, repeating the same actions over and over again to keep me from moving. I wasn't having fun, but neither were they.

As chapter three came to a close, I asked the table if anyone was having fun. After a moment of dead silence, they all agreed that no, nobody was having fun. We quietly packed up the game and played something else.

The Bloody Alternatives

While I cannot recommend that you spend your hard-earned money on Last Friday, those looking for a horror-themed deduction game are in luck. You have other options.

The first alternative would be (obviously) Letters From Whitechapel, a game that feels as lean, mean, and ruthlessly play tested as Last Friday feels bloated and broken. Here is a game that truly sings, rewarding ice cold logic, clear communication, and pure cunning. There's a reason Last Friday stole so liberally from this game – it's intense and scary genuinely makes everyone at the table feel like they're hunting and being hunted. It's sublime.

And if you want something heavier than Letters From Whitechapel, there's always Fury of Dracula, a "sequel" to Bram Stoker's original novel that follows a team of vampire hunters as they pursue the title villain across 19th century Europe. It's a more complex game with a higher learning curve, but its thematic richness is fuel for all kinds of beautiful, hilarious, and shocking emergent gameplay. Unlike Letters From Whitechapel, Fury of Dracula allows the Dracula player to turn the tables, emerge from their hidden movement, and take the fight right to their pursuers. Unfortunately, Fury of Dracula is on the verge of going out of print, but you can (and should) still snag a copy.

But what if you don't care about Jack the Ripper or Dracula and don't care about hidden movement deduction games and just want to play an '80s slasher board game? Then, and only then, may Last Friday be for you – it simply oozes theme and for some people, that may be enough. At the same time, the new gamer attracted to Last Friday for its theme instead of its mechanics may be put off by its obtuse structure and confusing choices. You're better off just breaking out that Friday the 13th Blu-ray box set again.