HDTGM: A Conversation With Brett Leonard, Director Of 'The Lawnmower Man'

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

In 2014, Facebook acquired Oculus—a scrappy start-up dedicated to resurrecting virtual reality—for $2 billion. Since then, every major player in the tech space (from Google and Microsoft to Sony and Samsung) has begun to prepare for a very virtual future.

With this incredible technology now on its way, I've spent the past couple of years working on a new book about the unlikely heroes of this virtual reality revolution. During that time, I've had hundreds of conversations with those in the burgeoning VR industry and, at some point, almost inevitably, The Lawnmower Man—the 1992 sci-film film directed by Brett Leonard—eventually comes up.

How Did This Get Made is a companion to the podcast How Did This Get Made with Paul Scheer, Jason Mantzoukas and June Diane Raphael which focuses on movies This regular feature is written by Blake J. Harris, who you might know as the writer of the book Console Wars, soon to be a motion picture produced by Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg. You can listen to The Lawnmower Man edition of the HDTGM podcast here. Synopsis: By utilizing the power of virtual reality, an eccentric scientist is able to transform a simple-minded gardener into a savant with telekinetic powers. But, as his intelligence grows, so does his thirst for revenge.Tagline: God made him simple. Science made him a god.

How Did This Get Made is a companion to the podcast How Did This Get Made with Paul Scheer, Jason Mantzoukas and June Diane Raphael which focuses on movies This regular feature is written by Blake J. Harris, who you might know as the writer of the book Console Wars, soon to be a motion picture produced by Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg. You can listen to The Lawnmower Man edition of the HDTGM podcast here. Synopsis: By utilizing the power of virtual reality, an eccentric scientist is able to transform a simple-minded gardener into a savant with telekinetic powers. But, as his intelligence grows, so does his thirst for revenge.Tagline: God made him simple. Science made him a god.

Some cite the film as an inspiration—an eye-opening experience that led them towards the career they have today—while others merely mention it as a frame of reference. Either way, it's pretty remarkable that, nearly 25 years later, a film would have that kind of influence. Remarkable...but not all that surprising. Because, as we've all come to learn, there are few things more powerful than story. This is a conversation about how that story came to be; and how, in shaping that story, director Brett Leonard came to believe that virtual reality is "going to be is the most transformative medium in the history of mankind."

Part 1: This Crazy Thing

Blake J. Harris: Most people know that you made the first mainstream movie about virtual reality. But not everyone realizes that, recently, you started a company to create VR content and, over the past 25 years, much of your career has been focused on the convergence between film and technology. So I was wondering: where did that start? Was it the tech that got you into film? Or did film take you into tech?Brett Leonard: It definitely started with movies. From the very first moment I saw one, which I think was when I was 2, at the drive-in with my parents.Blake J. Harris: Very early!Brett Leonard: Yeah. I was a kid from Toledo, Ohio and my mom was a fan of movies. She was kind of a frustrated actress, because she grew up in Toledo and never really got the chance to do it professionally. And so, from a very young age, she instilled that in me. And I just got a deep love of movies. Like it's the only thing I ever remember wanting to do as a child. So I left Toledo right after I got out of high school and headed to California to make my way in the movie business.Blake J. Harris: What did that entail? What was the route you took?Brett Leonard: Well, I had no money, no connections, no family, so I did it the hard way, I worked my way up. I started working as a grip. And I worked my way from working as a grip to directing by writing screenplays and then doing second unit camera work, second unit direction on low-budget films that would come up to Northern California where I was living in a place called Santa Cruz. And because I was in Santa Cruz I also was very in touch with the digital revolution, because that was sort of right next to Silicon Valley, so I fell in with people like Jobs and Wozniak and a guy named Jaron Lanier who was doing this thing called virtual reality.Blake J. Harris: What was it about VR in particular of all the technologies that you were seeing that really fascinated you?Brett Leonard: First of all, you have to understand the entire era. It was 1980, a very exciting era in the computer revolution. And it was all happening right there [laughs] and, by serendipity, people would come and smoke weed too so we all smoked weed together; these people who were all the digitary of the era. I mean, like everybody. All the Pixar guys. Everybody. It was this crazy thing.Blake J. Harris: That's awesome.Brett Leonard: So we started talking about these things back then, at these crazy parties in Santa Cruz. That had all these wild people. You know, "Captain Crunch," the great hacker, was part of it. And I was this young kid, filmmaker, who had done nothing yet, but was part of that group. I just fell into it and it was fascinating to me because I was always fascinated by science fiction. A bit of a technologist. And I wanted to combine those things in the films that I do vis-à-vis my main influence, which is Stanley Kubrick. I'm definitely a Kubrickian, and his merging of science and veracity. I saw 2001: A Space Odyssey when I was 7 years old and that's what really nailed me wanting to make movies. So in a weird way, I believe Kubrick is actually a pre-cursor to VR storytelling.Blake J. Harris: And how did what you saw—the stuff that Jaron and some others were working on—lead you to making The Lawnmower Man?Brett Leonard: So Jaron coined the term ["virtual reality"] and I popularized it with my movie. Before The Lawnmower Man, I actually made a film called The Dead Pit, was my first feature film. It was a zombie as many people start with zombie movies. [laughs] God love it, it's a great genre! And we shot that in an abandoned insane asylum in Northern California. And that got me the attention of the producers who wanted to do The Lawnmower Man.Blake J. Harris: Which producers? And what was the initial vision, if you recall?Brett Leonard: So my manager, Steve Freedman, showed The Dead Pit to a producing pair named Bob Pringle and Steve Lane. Bob and Steve saw the film and they were involved with an executive producer named Edward Simons who, with his partner Harvey Goldstein, had the rights to this 7-page short story by Stephen King called "The Lawnmower Man." It was a 7-page story about a guy telekinetically controlling a lawnmower. So I kind of brought this VR thing because I was hanging out with these people who were doing those kinds of things. I thought: man, this'll be a great concept for a movie and we can show where the technology is going.Blake J. Harris: So I'm assuming the original vision, for the film, was pretty similar to what's described in that 7-page story?Brett Leonard: Yeah. They had an initial concept that was a kind of local gardener, who was evil, who was using a mulching machine to chop up women and make them into fertilizer. I basically said: ehhhhh, I don't want to make that movie, but I got this other thing. And they're like: what the f***? I mean, literally. Virtual what? So I made a 20-minute educational video about virtual reality video using Sutherland footage and it's me, like against green screen, talking about virtual reality. Like I'm talking about to kindergarten children—aka producers—and that got them excited.Blake J. Harris: Did they buy in at that point? Did that have any lingering concerns?Brett Leonard: Well, they asked me, "how are you gonna do the effects? How are you gonna do that?" I said, "Don't worry, I've got that all figured out." [laughs] Of course I didn't. I didn't have any idea about that at all.

Part 2: The Greatest Lie in Hollywood

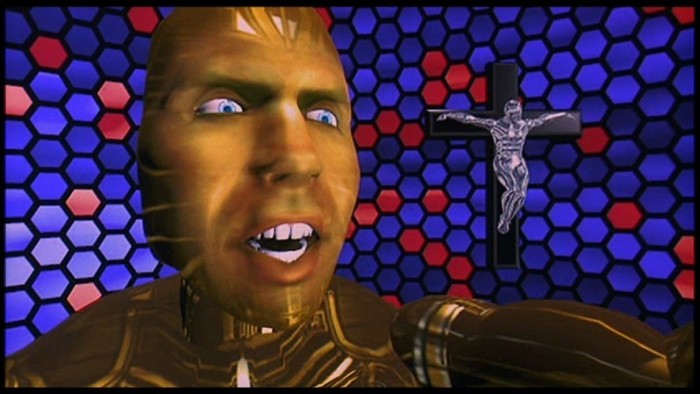

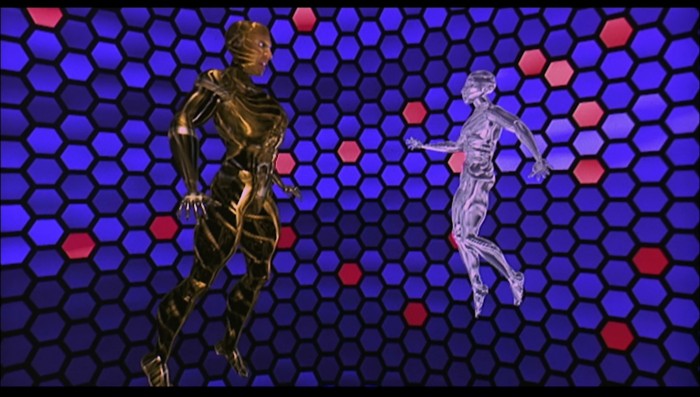

Blake J. Harris: So how did you deal with the special effects? There's a lot in the movie and this is the early 90s; computer-generated graphics are not very common.Brett Leonard: Right. It was at a time when computer graphics effects were not commoditized, there was ILM and nothing else. And we definitely couldn't afford ILM. Lawnmower Man started out as a very low-budget movie. $2 million, and I pumped it up to $5 million. But that still made it very tough. Luckily we were able to find these two very amazing talented groups: one called Angel Studios and the other was Chaos Images, which became a software company; they then productized the software they used to make The Lawnmower Man. Because of those two companies and the great team we had put together, and everyone thought the film was a $30 million movie.Blake J. Harris: Yeah, I'm surprised myself. I figured the budget was much higher than $5 million.Brett Leonard: And it made, in all markets, $250 million (that's including foreign markets, ancillary and everything). This was the number one independent film of 1992. The number one New Line film of that year. People call it a "cult film." It's a cult film in its concept, but it was very much a mainstream independent film from a financial standpoint. And that very much launched my career into the next tier in a big way.Blake J. Harris: What was next for you? Virtuosity?Brett Leonard: I did one film in between Lawnmower Man and Virtuosity, which is Hideaway with Jeff Goldblum, Christine Lahti, Alicia Silverstone and Jeremy Sisto. It's one of my littler known films, it's a supernatural thriller, but I'm very proud of it. And then out of those films, Paramount approached me.Blake J. Harris: In what capacity?Brett Leonard: Sherry Lansing and two producers, Gary Lucchesi and Howard Hawks Jr., they asked me to direct Virtuosity, which was in script development form at the time. And then I came on board and was very much a part of developing the script with the studio. [laughs] At one point, this is little known stuff, that I don't think I've talked about much: Michael Douglas was attached to the film.Blake J. Harris: Really? In the Russell Crowe role?Brett Leonard: No, no, no. In the Denzel Washington role. He was the first because Sherry had a real relationship with him and I met with him and we got along. He saw my movie and he was a fan. Then he had a knee injury and called me up and said, "Look, I can't run around. And this is a movie where I gotta run all the whole time; your movie is a big running movie. So I'm gonna go do The American President instead." And he did. And I'm glad he did, because I love that movie.Blake J. Harris: Yeah.Brett Leonard: And then Sherry turned to me and said, "Go get me Denzel." [laughs] And I literally had to hypnotize Denzel to get him in this movie. I met him on the set of Crimson Tide, he was shooting at the time with Tony Scott. We're there on this slanted bridge and I'm describing virtual reality. And no one knew what the f*** this thing was at that time, right? He's like, "I have no idea what you're talking about, but I think my son would love it. So let me think about this." And because of his son wanting him to do science fiction, and being into these kind of concepts, he said yes. That was a big moment. He had not done any science fiction at that time. He hadn't done anything like that. And it was rare for an actor like him to do that because there was a different audience for science fiction. There's a prejudice and stigma to doing those types of films. But Denzel didn't care and he's just an amazing actor; it was an absolute honor to work with him. And then when it came time to find the villain, I had this one wild meeting with Robert Downey Jr. He was not in the best shape at that time.Blake J. Harris: Ha, sure.Brett Leonard: It was prior to his Tony Stark days. But I loved him. He's amazing. But it was just too wild, too wild [laughs].Blake J. Harris: So how'd you end up with RC?Brett Leonard: My manager Steve Freedman and I had found this tape of this movie called Romper Stomper, which was a New Zealand independent movie that very few people saw here in the states. And it was Russell Crowe playing the character of Hando, this white supremacist gang leader. And this guy is heinous. I mean, he rapes his girlfriend, assaults Vietnamese immigrants...but you love him. Who the f*** is this guy? And I wanted a villain who was so charismatic you couldn't help but fall in love with him. And here was this guy that was evil as hell. So I went to Deborah Aquila, who was the head of casting for Paramount at the time. One of the top casting directors in the business for many, many years and she agreed with me that he was amazing. So we went to Sherry together and we got them to let us do a screen test (which I had to pay for).Blake J. Harris: Speaking of which, did you have to pay for that 20-minute Lawnmower Man "educational" film?Brett Leonard: Oh yeah, oh yeah.Blake J. Harris: Good for you.Brett Leonard: You need to do whatever it takes to make your case. Anyway, so we had the screen test. I flew Russell over on my own dime. We had the screen test and Denzel was very impressed as well. Denzel approved him and so did Sherry and I got Russell Crowe to play the villain.Blake J. Harris: That launched a pretty good career for Mr. Crowe...Brett Leonard: Yeah, well, there's this famous marketing meeting where we screened the film. The screening went very well, but the head of marketing stood up and said, "Well, great, we've got a f***ing Russell Crowe film." Because he was an unknown. They didn't know how to market it because he was so strong in the movie.Blake J. Harris: Ha!Brett Leonard: You know, he was an equal presence with Denzel...Blake J. Harris: Since these two movies were, really, the first time that many of us were hearing about and seeing the potential of virtual reality, how conscious were you about the type of message you wanted to send for this technology? Was that something you thought about a lot, or was it more just about telling a compelling story?Brett Leonard: You know, I thought at the time that true virtual reality—as it said at the beginning of The Lawnmower Man—would arrive at the turn of the millennium. Well it did come after the turn of the millennium, but quite a few years after. 10-15 years later than what I originally thought. But to answer your question about the technology: it was a contradiction for me. I was incredibly excited and stimulated by the discovering virtual reality and the potential of it. And simultaneously realized holy shit: this is going to be very powerful! And could be the ultimate Orwellian nightmare. So the stakes are high with something like this.Blake J. Harris: Right.Brett Leonard: With cinema, one of the great lies dating back to its origin was "It's just entertainment! It doesn't make any impact" Like the great Samuel Goldwyn said, "If you've got a message, send a telegram."Blake J. Harris: Ha.Brett Leonard: So there's a great lie here in Hollywood that cinema—what we do—it "doesn't count." It is important. It affects global culture. It creates global culture. My life has been completely affected by cinema. It's an important medium and so is VR to a much greater degree. It literally changes our minds. And that's something that's both exhilarating, from the standpoint of "how can we evolve ourselves" and terrifying. Just like most of trans humanism is exhilarating and terrifying. So as a storyteller, it's rich fodder for exploring those themes. So I was very cognizant of those themes. And my partner, Gimel Everett, who was my partner in life at the time, and also my screenwriting partner, we were very much focused on that. And Gimel was a very spiritual person. And really taught me a lot about that. So she was my guide in really bringing me to see the greater sort of spiritual implications of this medium. Blake J. Harris: You mentioned, just a little bit earlier, that you envisioned that virtual reality would really take hold around the turn of the millennium. That didn't happen. And not only that, many of the companies that were formed in the 90s—those looking to usher in the virtual era—they failed. The revolution didn't happen, at least not then. Did you ever suspect that it wouldn't happen at all?Brett Leonard: Well, it's a continuum. Like if you look at the automobile business, it took decades for it to really ratchet up. It's just a continuum. We see it from a very myopic standpoint because we're so close to it right now. But, you know, all of the things that have been worked on from that time in the 90s until now really have affected where we are now and are responsible for making this happen. That's why I think it's really important to have inter-generational relationships right; some level of communication between us silver-backed gorillas, who have been looking at and working on these problems for years, and the next generation of problem-solvers. And it's happening. So it's a very exciting time because of it. And a lot of the young people I'm working with, it's very exciting. Their enthusiasm, the revolutionary nature of what they're doing, what they're being driven by...Blake J. Harris: Yeah, it's an incredibly exciting time. Every day I'm interviewing people for the book, and every day and surprised and amazed by what's going on.Brett Leonard: And it's great fun because we're making it up as we go along. We're bringing very unique people to the table to talk to each other. For what I call, facetiously, an "unholy alliance." Basically what that is referencing is you need to bring people together who wouldn't usually talk to each other. And really get them to find a common language to create this new medium. And what I believe it's going to be is the most transformative medium in the history of mankind. And it also has the potential to be something far more negative, something darker. And that's why I'm going to continue to tell cautionary tales...I mean the irony of my life is that I'm primarily a cautionary-tale teller, but you popularized the very thing you're cautioning.Blake J. Harris: [laughs] Well let's finish by talking about that: your company, what's coming down the pipe and, of course, the art of telling stories in virtual reality.

Blake J. Harris: You mentioned, just a little bit earlier, that you envisioned that virtual reality would really take hold around the turn of the millennium. That didn't happen. And not only that, many of the companies that were formed in the 90s—those looking to usher in the virtual era—they failed. The revolution didn't happen, at least not then. Did you ever suspect that it wouldn't happen at all?Brett Leonard: Well, it's a continuum. Like if you look at the automobile business, it took decades for it to really ratchet up. It's just a continuum. We see it from a very myopic standpoint because we're so close to it right now. But, you know, all of the things that have been worked on from that time in the 90s until now really have affected where we are now and are responsible for making this happen. That's why I think it's really important to have inter-generational relationships right; some level of communication between us silver-backed gorillas, who have been looking at and working on these problems for years, and the next generation of problem-solvers. And it's happening. So it's a very exciting time because of it. And a lot of the young people I'm working with, it's very exciting. Their enthusiasm, the revolutionary nature of what they're doing, what they're being driven by...Blake J. Harris: Yeah, it's an incredibly exciting time. Every day I'm interviewing people for the book, and every day and surprised and amazed by what's going on.Brett Leonard: And it's great fun because we're making it up as we go along. We're bringing very unique people to the table to talk to each other. For what I call, facetiously, an "unholy alliance." Basically what that is referencing is you need to bring people together who wouldn't usually talk to each other. And really get them to find a common language to create this new medium. And what I believe it's going to be is the most transformative medium in the history of mankind. And it also has the potential to be something far more negative, something darker. And that's why I'm going to continue to tell cautionary tales...I mean the irony of my life is that I'm primarily a cautionary-tale teller, but you popularized the very thing you're cautioning.Blake J. Harris: [laughs] Well let's finish by talking about that: your company, what's coming down the pipe and, of course, the art of telling stories in virtual reality.

Part 3: Storytellers and the Art of Story-Worlding

Blake J. Harris: Let's start with your company: Virtuosity...Brett Leonard: Yeah. So it's a company I started with Scott Ross, who ran ILM and Lucasfilm for George Lucas, and with David Goldman, who was an uber-agent—Will Smith's agent, Mick Jagger's agent—and also ran William Morris for many years. So we're out there, they're calling us "the adults in the room."Blake J. Harris: Ha!Brett Leonard: I mean, look, there's a ton of young companies and they're fantastic in the innovative spirit. But delivering this motherf***er is going to be really tough.Blake J. Harris: Absolutely. And you said that you thought VR is going to be "the most transformative medium in the history of mankind." How so?Brett Leonard: Well, it's a truly immersive medium and the level of graphics, already quite strong, will only continue to get better and better. You really feel like you are someplace else...and what you see, what you experience, it impacts your brain. So there are major implications here, to societal structure, to democracy to the way in which we interact with each other. To the nature of love, to the nature of sexuality.Blake J. Harris: Right. If you think about something like The Matrix, then anything truly becomes possible.Brett Leonard: Yeah, so in some ways I feel...not that I created the thing, but I was a storyteller. In some ways, I was the jester, the harlequin who took it out there, I feel a bit of a karmic responsibly to help guide it in the right direction. Because I feel that connection to it. And I have a 21 year old son and he's going to be living in that world that VR will create. That's why my number one rule of VR is: take it seriously, the stakes are high. Do not underestimate the virtual world's ability to influence the actual world.Blake J. Harris: You're right. There is a lot at stake. And also lots of incredible tools at your disposal. How does that impact you as a storyteller? Or perhaps an easier place to begin: How does telling a story in VR compare to telling a story on film?Brett Leonard: This is much harder than doing any of those things we've already done. Primarily because this is a multi-disciplinary medium. We have neurologists and behavioral psychologists and people like that on our team because you're creating reality. That's an example of the multi-disciplinary approach we need to take in order to skin the cat. Because this thing is inherently the anti-thesis, in some ways, of what cinema is. And yet, the paradox is that it utilizes certain aspects of cinematic craft. And in my mind, cinematic theory such as the theory of off-screen space. Which is what you don't show in a cinematic that leads to comprehension and understanding by the audience. And how that's more important than what you do show; because film is a shorthand medium. This is a true long-form medium, much more akin to exploring a novel or exploring architecture. So I'm utilizing cinematic aspects, theories, and craft in the creation of a story world. I'm becoming a story-worlder in the space of actual virtual reality. The thing that's the same, I believe, as what happened back then—this is a critical phase, billions of dollars are going into this now, the tech is being supported by every major consumer electronics company—but now the content and what it really is has to, in a sense, inform people of what the medium is. Similar to what I did in my movies...Blake J. Harris: And how would you describe what it is you are trying to accomplish?Brett Leonard: My focus is to push the medium to be what it truly can be. Something well beyond 360-video, which is where a lot of the initial money has gone...but, of course, it's not real VR if you don't have agency. So what I've been looking for for 25 years is that undiscovered country between gameplay and linear narrative and the emotional engagement of a cinematic narrative. And that takes a huge combination of interesting technological enablements, as well as an understanding of how to bring a multidisciplinary team on a process that is upside-down the traditional process.Blake J. Harris: You're talking about the storytelling form of VR being more similar to a novel than a traditional film. Where do you see videogames fitting into this? Especially open-world games?Brett Leonard: Videogame designers inherently understand VR a little better than those coming from cinema. At the same time, there's something that next-generation VR is going to need to bring into it: which is true, emotional engagement. The kind of emotional engagement you get in a narrative cinematic experiences; that's part of what I mean by bringing these "unholy alliances" together. And there's also other things happening, much of the content is being designed with game engines...By "game engines," Leonard is referring to ones like those made by Unity, which enables developers—particularly indie developers, who don't have the resources of a big studio—to create (or buy) 3D assets and build immersive virtual worlds.Brett Leonard: I liken it to the time in cinema before the feature film. There were one-reelers and two-reelers, these 10-20 minute experiences, and the movie business was kind of a nickel and dime business. And then D.W. Griffith came along and invented the feature film. And that changed everything. And of course, at the time, he was ridiculed for presuming people would want to spend more than 10-20 minutes watching a film. It's all the same shit you're hearing about VR right now. The same thing. And then that crated the form, the product, that formed the entire Hollywood model. And that's the moment we're about to be in.Blake J. Harris: One last question for you: as someone who had an eye on VR when most of the world had either forgotten or given-up, I'm curious what's been the most surprising thing to you about how these last few years have played out.Brett Leonard: So things really began to change in 2014, that's when Palmer Luckey and Oculus were able to get Mark Zuckerberg excited about VR to the tune of $2 billion! And that made everything f***ing go into hyper speed. It really launched this new moment. In terms of what surprised me most...I was surprised by the amount of money that was being thrown at 360-video.Blake J. Harris: By which you mean immersive, cinematic worlds, but in which you have no agency to move around and interact, right?Brett Leonard: Yeah. I think 360-video is valid and can be entertaining, but it's not true VR. It might be a step to true VR. But you're gonna see some of those companies hitting the wall because the business model doesn't make sense for 360-video. And that could hurt the medium a little bit. So I'm surprised at that aspect. I'm also surprised that so much money has gone into the tech as opposed to the content. Because the razors are one thing, but the razor blades are where you make the money and what is really important. But that's starting to pivot. So I think 2017 is going to be the year of next-gen VR content creation. And the other surprising thing is China. China: oh my god! They've taken to it like it never didn't exist. It's just wild. And that is going to be a very interesting market to deal with and be a part of. Someone in the industry recently said to me, "if you don't have a China strategy, you don't have a VR strategy."