HDTGM: A Conversation With Stewart Raffill, Director Of Mannequin 2

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

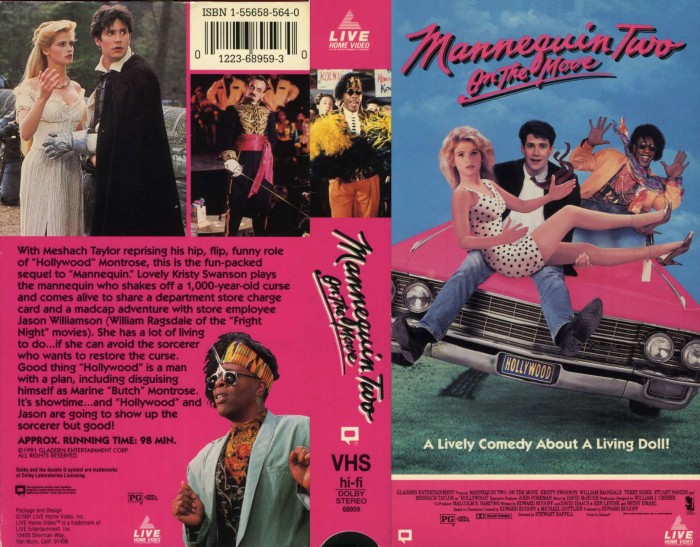

Following an unexpected success with the '80s rom-com Mannequin, the reasons why a sequel were made are about as interesting (and artistically-driven) as one would imagine. But one aspect of that sequel—Mannequin 2: On the Move—that's especially interesting is the film's director: Stewart Raffill.

Stewart Raffill is a guy who broke into the business by training lions, tigers and bears. A guy who directed an award-winning sci-fi film and then, three years later, took home the Razzie for worst director. And also a guy who wrote one of my favorite childhood films, although the version I saw was much different from the one he had envisioned. I sat down with Raffill to discuss all those things and, of course, get the inscape scoop on Mannequin 2.

How Did This Get Made is a companion to the podcast How Did This Get Made with Paul Scheer, Jason Mantzoukas and June Diane Raphael which focuses on movies This regular feature is written by Blake J. Harris, who you might know as the writer of the book Console Wars, soon to be a motion picture produced by Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg. You can listen to the Simply Irresistible edition of the HDTGM podcast here. Synopsis: A young department store employee falls in love with a female store mannequin who, as it turns out, is actually a gorgeous peasant girl who's been cursed into a frozen trance for a thousand years.Tagline: A Lively Comedy about a Living Doll

How Did This Get Made is a companion to the podcast How Did This Get Made with Paul Scheer, Jason Mantzoukas and June Diane Raphael which focuses on movies This regular feature is written by Blake J. Harris, who you might know as the writer of the book Console Wars, soon to be a motion picture produced by Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg. You can listen to the Simply Irresistible edition of the HDTGM podcast here. Synopsis: A young department store employee falls in love with a female store mannequin who, as it turns out, is actually a gorgeous peasant girl who's been cursed into a frozen trance for a thousand years.Tagline: A Lively Comedy about a Living Doll

Part 1: A Lion Walks Into an Elevator

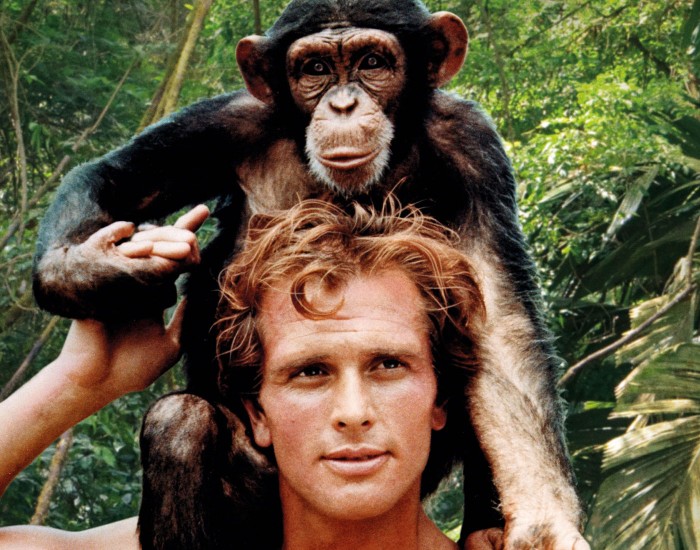

Blake J. Harris: Stewart, before we get into Mannequin 2, I was curious to hear how you first got into film and television.Stewart Raffill: Well, I didn't really do too much television. I really went straight into film.Blake J. Harris: Sorry about that. I thought you got your start on that Tarzan TV series from the '60s.Stewart Raffill: Oh, ah yes. I used to have a company that rented wild animals to the studios. That was my first business. I used to do the stunt work for Tarzan. A couple different Tarzans. In Brazil and Mexico and a couple different places where they filmed them. Then I got into independent filmmaking after that.Blake J. Harris: Wow, I didn't realize you rented out wild animals. How did that happen? Or rather, before that, how did you even know how to train animals?Stewart Raffill: Well, I grew up on a farm in England. We used to have horses that we raced and everything. So it was a natural for me to be around animals. And I got my degree in agriculture. Then, when I was 18 years old, I came here on the Queen Mary. I never had any connection with film or TV until I went into the business of supplying animals. It's an interesting business because you spend every day of your life on set watching other people directing and producing. It was an eye-opener.Blake J. Harris: What types of animals did you train?Stewart Raffill: Lions, tigers, elephants, chimpanzees. All those creatures. Grizzles too.Blake J. Harris: Did you have a favorite animal to work with?Stewart Raffill: No, I liked them all. The chimps are the most interesting, but the most dangerous. Elephants are pretty nice to work with. Big cats: they're all individuals, so you need to figure out how to work with them. And big bears are usually pretty smart and nice to work with too. It just depends on the story. Blake J. Harris: How did you used to prepare the animals for being on camera?Stewart Raffill: You have to get them as cubs and raise them. You know, this was a long time ago. Nowadays, it's pretty hard for anybody to get any cubs of any kind. There's all sorts of restrictions. Game department gets involved with everything. The whole thing changed. I mean, there was a time I used to walk down Hollywood Boulevard with my lion on a chain.Blake J. Harris: Really?Stewart Raffill: Used to drive into town with him in the back seat of the car. Took him up until a building. There was a guy called Sy Weintraub that was going to do the original Tarzan television series. And he was in the last office building on Sunset. And myself and a friend. Do you remember Grizzly Adams?Blake J. Harris: Yeah.Stewart Raffill: Yeah, Dan Haggerty, he worked for me in those days and we took the leopard, the lion and a big chimp and we stopped at this big high rise at the end of Sunset Boulevard. The last building before you go into Beverly Hills. And we pulled up in front—got the cats and the chimp out—walked into the lobby. People just...they didn't know how to react. Got into the elevator. Went up to the 11th floor. Walked into the guy's office and said if you're doing a new TV series about Tarzan these are the animals you need. And he hired him.Blake J. Harris: That's so amazing.Stewart Raffill: It was kind of funny because when we left, the elevator stopped at a couple of floors. And most people just stopped and said, "Oh man! Are you kidding!!" One guy, who was like too tough to react, he got in there and just stood there kind of sweating and pretending it wasn't happening.Blake J. Harris: That's a great visual.Stewart Raffill: It was a very great visual.Blake J. Harris: So I'm assuming at some point along the way you stopped training animals, right?Stewart Raffill: [laughing] Yes. Right now I have a little Shih Tzu, that's the only animal I have left.

Blake J. Harris: How did you used to prepare the animals for being on camera?Stewart Raffill: You have to get them as cubs and raise them. You know, this was a long time ago. Nowadays, it's pretty hard for anybody to get any cubs of any kind. There's all sorts of restrictions. Game department gets involved with everything. The whole thing changed. I mean, there was a time I used to walk down Hollywood Boulevard with my lion on a chain.Blake J. Harris: Really?Stewart Raffill: Used to drive into town with him in the back seat of the car. Took him up until a building. There was a guy called Sy Weintraub that was going to do the original Tarzan television series. And he was in the last office building on Sunset. And myself and a friend. Do you remember Grizzly Adams?Blake J. Harris: Yeah.Stewart Raffill: Yeah, Dan Haggerty, he worked for me in those days and we took the leopard, the lion and a big chimp and we stopped at this big high rise at the end of Sunset Boulevard. The last building before you go into Beverly Hills. And we pulled up in front—got the cats and the chimp out—walked into the lobby. People just...they didn't know how to react. Got into the elevator. Went up to the 11th floor. Walked into the guy's office and said if you're doing a new TV series about Tarzan these are the animals you need. And he hired him.Blake J. Harris: That's so amazing.Stewart Raffill: It was kind of funny because when we left, the elevator stopped at a couple of floors. And most people just stopped and said, "Oh man! Are you kidding!!" One guy, who was like too tough to react, he got in there and just stood there kind of sweating and pretending it wasn't happening.Blake J. Harris: That's a great visual.Stewart Raffill: It was a very great visual.Blake J. Harris: So I'm assuming at some point along the way you stopped training animals, right?Stewart Raffill: [laughing] Yes. Right now I have a little Shih Tzu, that's the only animal I have left.

Part 2: The Politics of Hollywood

Stewart Raffill: What happened was I used some of the money from from renting animals and I made my first movie, a kid's movie, down at the Okefenokee Swamp down in Georgia. The Tender Warrior [1971]. And then sold that to Warner Bros. They didn't do much. Bought it back and then re-distributed it with someone else. Then did things like [The Adventures of] the Wilderness Family that became quite successful. Independent family films with lots of animals and kids.Blake J. Harris: That's a pretty fun niche.Stewart Raffill: It was. I did quite a few family films. The second script I wrote was a thing called Napoleon and Samantha, which I sold to Disney. I was one of the producers on it and I had the pet lion on it. I believe that was Jodie Foster's first job and Michael Douglas' first film as a star.Blake J. Harris: Oh, wow. What was that experience like?Stewart Raffill: That was great. I mean Walt Disney was still alive in those days. The studio was a very lively place. And then, of course, he died and it went through all sorts of transitions and it became a conglomerate. It became less personal, as far as I'm concerned. Blake J. Harris: You either wrote or directed about ten films during the '70s and '80s. Does any stand out as a favorite?Stewart Raffill: Probably High Risk. With Anthony Quinn, James Coburn, Jim Brolin, Lindsay Wagner and Ernest Borgnine. I made that in Mexico with a Mexican crew. Then after that, I got hired by John Forman and David Begelman—who were over at MGM—to do a movie called The Ice Pirates. We did that at the old MGM. In fact it was the last film that was shot on that lot before it became part of Sony. And of course David Begelman and John Forman were the producers on Mannequin: On the Move, the second one.Blake J. Harris: Right. The beginning of a fruitful relationship. How did they find you?Stewart Raffill: David was the head of the studio, MGM. And the studio had not been doing well. So the bank put a limit of $8 million on each movie they made. Which put a project they'd been developing into real jeopardy. A project called The Water Planet. The budget was, like, $20 million, so they came to me and asked if this was something I could make for $8 million. I said I'd have to re-write it and make it into a comedy or something. That worked for them. The studio had a contract with Bob Urich at that time, for a TV series, so they wanted him in it. So that's how it came about. But it ended up being a fiasco.Blake J. Harris: How so?Stewart Raffill: Because MGM went through a transition and they brought in a new guy, who was eventually found out to be stealing money from the company. He was a little problematic sort of a fellow. And he had a bad time with John Foreman so he tried to sabotage the film. Pulled the money out on them, but we did finish it. [long sigh] The politics of Hollywood.

Blake J. Harris: You either wrote or directed about ten films during the '70s and '80s. Does any stand out as a favorite?Stewart Raffill: Probably High Risk. With Anthony Quinn, James Coburn, Jim Brolin, Lindsay Wagner and Ernest Borgnine. I made that in Mexico with a Mexican crew. Then after that, I got hired by John Forman and David Begelman—who were over at MGM—to do a movie called The Ice Pirates. We did that at the old MGM. In fact it was the last film that was shot on that lot before it became part of Sony. And of course David Begelman and John Forman were the producers on Mannequin: On the Move, the second one.Blake J. Harris: Right. The beginning of a fruitful relationship. How did they find you?Stewart Raffill: David was the head of the studio, MGM. And the studio had not been doing well. So the bank put a limit of $8 million on each movie they made. Which put a project they'd been developing into real jeopardy. A project called The Water Planet. The budget was, like, $20 million, so they came to me and asked if this was something I could make for $8 million. I said I'd have to re-write it and make it into a comedy or something. That worked for them. The studio had a contract with Bob Urich at that time, for a TV series, so they wanted him in it. So that's how it came about. But it ended up being a fiasco.Blake J. Harris: How so?Stewart Raffill: Because MGM went through a transition and they brought in a new guy, who was eventually found out to be stealing money from the company. He was a little problematic sort of a fellow. And he had a bad time with John Foreman so he tried to sabotage the film. Pulled the money out on them, but we did finish it. [long sigh] The politics of Hollywood.

Part 3: On the Move

Blake J. Harris: So how did Mannequin 2 happen?Stewart Raffill: David [Begelman] owned the company that did the original, and it was very successful, so they just decided to make a sequel. They had a screenplay written, and they were just looking for someone to make it for a sensible price. They called me up and I just finished a thing called The Philadelphia Experiment. This project was a comedy and it seemed like it could be fun. So I said, "I'll do it."Blake J. Harris: And how familiar were you with that first Mannequin movie?Stewart Raffill: I wasn't at all. Had never seen it. This was one of those "Can you do it?" "Yes I can" situations. John Foreman was a close friend of mine. There was money in the bank. Sure, let's do it.Blake J. Harris: You mentioned that there was already a script in place. Did it change much after you came on board? Did you weigh in on it?Stewart Raffill: No, I didn't. That was part of the deal. Just do this thing.Blake J. Harris: What do you remember about the filming?Stewart Raffill: I remember how beautiful the girl was in it.Blake J. Harris: Yeah, she was. Kristy Swanson was great. Stewart Raffill: Oh, she was just such a beautiful girl, she was. And it's a shame, you know, because she was the original Buffy the Vampire Slayer. And when they came to do the series, she was a celebrity and she said, "I don't want to go into TV." Which was the biggest mistake ever. Because TV became the pre-eminent medium, really, for making money for actors. And features has been on the decline for several decades.Blake J. Harris: What about the rest of the cast? Where did they come from?Stewart Raffill: Well, Meshach [Taylor] had been in the first one. And the boy in it, I forget his name [William Ragsdale], he was kind of an up-and-coming yuppie love-interest. But he never went anywhere after that. And then that was it.Blake J. Harris: What about Terry Kiser?Stewart Raffill: Oh, he was amazing. You know, he eventually got fed up with Hollywood and moved to Colorado. Then he went out of business. I put him in another low-budget film I made. He was a wonderful, eccentric fun character who just disappeared, you know? He did Weekend at Bernie's and that was it. They already thought he was dead.Blake J. Harris: And what about those three tough guys? I think, maybe, they were foreign. Do you remember them? The comic relief?Stewart Raffill: I call them the goons. The muscle guys. They were all weightlifters.Blake J. Harris: Exactly, yeah. I think their voices were dubbed. How come?Stewart Raffill: Because they just weren't actors. Just muscular guys that they hire because of their looks. Never acted before. And just didn't have that vocal ability. To be real or even just say simple things like, "Look out!"

Stewart Raffill: Oh, she was just such a beautiful girl, she was. And it's a shame, you know, because she was the original Buffy the Vampire Slayer. And when they came to do the series, she was a celebrity and she said, "I don't want to go into TV." Which was the biggest mistake ever. Because TV became the pre-eminent medium, really, for making money for actors. And features has been on the decline for several decades.Blake J. Harris: What about the rest of the cast? Where did they come from?Stewart Raffill: Well, Meshach [Taylor] had been in the first one. And the boy in it, I forget his name [William Ragsdale], he was kind of an up-and-coming yuppie love-interest. But he never went anywhere after that. And then that was it.Blake J. Harris: What about Terry Kiser?Stewart Raffill: Oh, he was amazing. You know, he eventually got fed up with Hollywood and moved to Colorado. Then he went out of business. I put him in another low-budget film I made. He was a wonderful, eccentric fun character who just disappeared, you know? He did Weekend at Bernie's and that was it. They already thought he was dead.Blake J. Harris: And what about those three tough guys? I think, maybe, they were foreign. Do you remember them? The comic relief?Stewart Raffill: I call them the goons. The muscle guys. They were all weightlifters.Blake J. Harris: Exactly, yeah. I think their voices were dubbed. How come?Stewart Raffill: Because they just weren't actors. Just muscular guys that they hire because of their looks. Never acted before. And just didn't have that vocal ability. To be real or even just say simple things like, "Look out!" Blake J. Harris: [laughter] Compared to most of the other films you'd been doing—be it The Philadelphia Experiment or family films with animals—this one was a bit different. So how did you approach that? The sensibility?Stewart Raffill: The main thing was just to play the humor. It's a situation comedy so you have to set up the situation. It's obviously an outlandish idea—it's an inanimate thing and then it comes to life—so in that structure you have all sorts of humor. Particularly if the person is just suddenly falling in love. You want that person's reactions to be interesting, so you try to come up with scenes that, you know, take advantage of that particular configuration of comedy potentials.Blake J. Harris: Do you remember what the most challenging part of filming was?Stewart Raffill: It was not a very challenging movie. I mean, it was a very simple film to make because it mostly took place in a big store. This place called Wanamaker's, which is one of the great stores of Philadelphia (and one of the first department stores in the United States). So that went well. It was a good shoot. And Kristy was a charm to work with. Very accessible and not spoiled in any way. She was just a neophyte as far as being an actor is concerned, but she played that part pretty well.Blake J. Harris: Yeah, she was charming.Stewart Raffill: It's a cute movie. Maybe they need some more things like that nowadays. But innocence has sort of faded, hasn't it? That type of innocent humor. This was an era when, you know, simpler values existed.

Blake J. Harris: [laughter] Compared to most of the other films you'd been doing—be it The Philadelphia Experiment or family films with animals—this one was a bit different. So how did you approach that? The sensibility?Stewart Raffill: The main thing was just to play the humor. It's a situation comedy so you have to set up the situation. It's obviously an outlandish idea—it's an inanimate thing and then it comes to life—so in that structure you have all sorts of humor. Particularly if the person is just suddenly falling in love. You want that person's reactions to be interesting, so you try to come up with scenes that, you know, take advantage of that particular configuration of comedy potentials.Blake J. Harris: Do you remember what the most challenging part of filming was?Stewart Raffill: It was not a very challenging movie. I mean, it was a very simple film to make because it mostly took place in a big store. This place called Wanamaker's, which is one of the great stores of Philadelphia (and one of the first department stores in the United States). So that went well. It was a good shoot. And Kristy was a charm to work with. Very accessible and not spoiled in any way. She was just a neophyte as far as being an actor is concerned, but she played that part pretty well.Blake J. Harris: Yeah, she was charming.Stewart Raffill: It's a cute movie. Maybe they need some more things like that nowadays. But innocence has sort of faded, hasn't it? That type of innocent humor. This was an era when, you know, simpler values existed.

Part 4: Mac and Me

Stewart Raffill: Mac and Me? That was another movie where somebody called me up and he was a producer who had worked on quite a few films. He'd made a lot of big movies, but he decided he want to make his own movie. And he raised the money from one of the main partners at McDonalds—I think, like, the produce provider for McDonalds—and he put up the money to do that movie with the understanding that the proceeds from that movie would go to the Ronald McDonald Foundation.Blake J. Harris: That's...unusual.Stewart Raffill: Just wait. So I was hired out of the blue. And the producer asked me to come down to the office. So I did and he had a whole crew there, a whole crew on the payroll. It was amazing. He had the transportation captain. The camera department head. The AD. The Production Manager. He had everybody already hired and I said, "Well, what's the script?" And he said, "We don't have a script. I don't like the script. You have to write the script. You're gonna have to write it quick so prep the movie and write the script on the weekends."Blake J. Harris: No way. Really? Did you?Stewart Raffill: Yeah, so I'd go and lock myself in a hotel on Friday night, write 'til Monday, anticipate what the locations were going to be, go out and find the locations, design the aliens and all that stuff. It was kind of a messy way to make a movie.Blake J. Harris: Of course.Stewart Raffill: The interesting thing was the guy wanted to do a film with a real...you know, he wanted to help someone who was handicapped. So he found a kid who had spina bifida. The kid had never acted before, but he was a wonderful kid. But when they finished it was as if the fact that they used a real encumbered person to play the person didn't mean anything to even the people who lived in the world. You'd think that if you made a movie about a kid with spina bifida and you really used a real kid with spina bifida, it would be something unique for the millions of people in the country who have spina bifida or their parents or anyone who's life has been affected by it.Blake J. Harris: If nothing else, I'm surprised that wasn't part of the marketing.Stewart Raffill: Right? So that was Mac and Me. "Would you be interested in directing an alien movie with a kid that's handicapped for kids for the McDonalds Company. And we gotta do it quick." I said yes and just made it up and there you go.

Part 5: How Scripts Evolve

Blake J. Harris: Before we finish, there was one project I feel compelled to ask about. Passenger 57. A longtime favorite in the Harris household. I didn't realize that you were the screenwriter on that. How did that come about?Stewart Raffill: Well, that's a whole different story. That was a great script that I had written and everybody in town loved it. But it was a very...the original story was about a guy liked Clint Eastwood and it was about a guy who went to bury his son in Spain and on this plane he sat next to some urbane guy from Iran. And the guy from Iran turns out to be a terrorist and they highjack the plane and take all the Americans to Iran. And they take them off the plane and they put them in to different cells and they kept them all away. And Clint Eastwood, through the whole thing, is watching this guy and eventually gets the gun. Shoots a whole bunch and says, "Who are the people running this country?" The Mullahs. He says, "Okay" and he goes to where the Mullahs are and he takes all the Mullahs as prisoners and he holds them as prisoners to exchange for all the Americans there and then fights his way out of Iran. That was the original story. Way too political.Blake J. Harris: Haha.Stewart Raffill: The head of the studio said to me, "If I make that movie, they'll blow up the theaters." So I did a couple of re-writes for them, for Warner Bros who owned it, then I got another picture and came back and then it became a black movie. And that was it.Blake J. Harris: So you didn't write that famous line "Always bet on black?"Stewart Raffill: No I didn't because there wasn't any black people in it when I wrote it.Blake J. Harris: So one final question. Good or bad, Passenger 57—the version that was shot—was pretty different from your initial vision. And with movies like Mannequin 2 and Mac and Me, these weren't really your creative vision to begin with. So I was just curious, during this time—the '80s and '90s—which movie, or movies, you think are most reflective of your artistic sensibilities. Stewart Raffill: I'd say The Philadelphia Experiment. By the time I got involved, that movie had been rewritten 9 times. I was doing the Ice Pirates for MGM at that time, but there was a Canadian guy who was supposed to do the next re-write and I said I'd do it subject to the screenplay coming in. But when it came in, the screenplay was terrible. So I said to my agent, "I just can't do this. The script doesn't even make sense." And he said, "You're going to have to tell the head of the studio." So I spoke to the head of Universal for a while and I told him I didn't want to do it. He said, "Well what did you want to do?" I said it should have been this and this and this. And I told him what I had envisioned. Then he said, "Alright, well, why don't you make that movie?" And I said, "Because I'm supposed to start shooting it in three weeks."Blake J. Harris: Oh wow.Stewart Raffill: So he asked if I had ever dictated a screenplay before. I told him I had not. Then he said, "Well, I'm gonna send someone to your house, a girl, every afternoon, and just dictate the story you told me and fill in the dialogue and we'll make that." And I said, "Okay." So that's what I did."Blake J. Harris: Worked out pretty well.Stewart Raffill: It did. Though the funny thing is that I never even got a writing credit on that one. Oh well.

Stewart Raffill: I'd say The Philadelphia Experiment. By the time I got involved, that movie had been rewritten 9 times. I was doing the Ice Pirates for MGM at that time, but there was a Canadian guy who was supposed to do the next re-write and I said I'd do it subject to the screenplay coming in. But when it came in, the screenplay was terrible. So I said to my agent, "I just can't do this. The script doesn't even make sense." And he said, "You're going to have to tell the head of the studio." So I spoke to the head of Universal for a while and I told him I didn't want to do it. He said, "Well what did you want to do?" I said it should have been this and this and this. And I told him what I had envisioned. Then he said, "Alright, well, why don't you make that movie?" And I said, "Because I'm supposed to start shooting it in three weeks."Blake J. Harris: Oh wow.Stewart Raffill: So he asked if I had ever dictated a screenplay before. I told him I had not. Then he said, "Well, I'm gonna send someone to your house, a girl, every afternoon, and just dictate the story you told me and fill in the dialogue and we'll make that." And I said, "Okay." So that's what I did."Blake J. Harris: Worked out pretty well.Stewart Raffill: It did. Though the funny thing is that I never even got a writing credit on that one. Oh well.