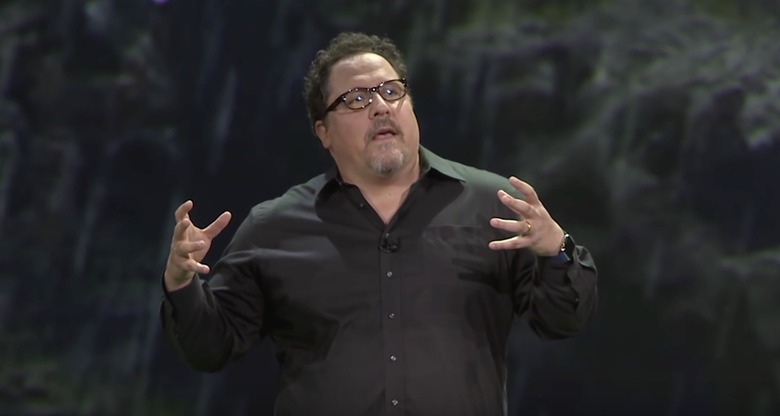

Interview: 'The Jungle Book' Director Jon Favreau On Modernizing A Disney Classic

The Jungle Book is arguably director Jon Favreau's most ambitious film to date. The filmmaker behind Iron Man and Chef reimagines the 1967 Disney animated classic on a grand scale. 98% of The Jungle Book is CGI, and bringing those environments to life, over a two-year process, was quite an undertaking for Favreau and all involved.

With the film, which was actually influenced by the likes of Goodfellas and classic westerns, Favreau tells a surprisingly intimate comig-of-age tale on a massive canvas. To learn how the director and his team came together to retell author Rudyard Kipling's story, read our Jon Favreau interview below.

Both The Jungle Book and Cinderella capture the spirit of the original animated films, but it seems like you had to make more deviations.

Because of the nature of the original Jungle Book, the '67 animated feature, we had to depart from it more than [Cinderella director Kenneth] Branagh had to, inherently, because if you just made that movie live-action, I think it would have been odd. We went for a PG movie, as opposed to a G-rated kids' musical. We had to draw inspiration, not just from Jungle Book, but also films like Lion King and the big five animated ones.

Certainly, what Branagh did, and what was done with Maleficent, gave the studio and myself confidence that there is a curiosity, an underlying curiosity, for re-tellings of these stories using new technology. Disney was comfortable enough to say, "Hey, let's really go for it," in the style of Life of Pi and Avatar, and go photo-real and see what technology has to offer. To have those tools available for something other than a superhero movie was a big treat for me.

With that PG rating, there are some dark moments in the film, at least by kids movies' standards. How far can you push that sense of danger?

There are a few things. One, was the PG rating. I knew that if we were PG, we were sticking... Actually, the MPAA was helpful as a determinant, and there was nothing that we had to even trim from any version that we had, because we never showed anything on camera. Also, knowing that Walt [Disney] would spend a lot of time, even in the scariest moments, building the tension. If you think of Snow White, but never really showing much on camera, on screen, you never really see anything happen. Most things are reaction shots or build up or music. I think the fact that it's photo-real and, especially if you're seeing it in a large format, it inherently makes it more exciting.

Then, we looked at movies like Lion King, where they had music and they had funny moments, really broadly funny moments, but also death and a sense of stakes and fear. I think that the thing that probably, as a parent, makes me most comfortable is that, ultimately, what the message of the film is and ultimately what the mood is and the balance of humor.

The jury is out, we'll see. We'll see how people feel. I say as a parent, you know your kid. If the kid sees the trailer and doesn't like the trailer, then the movie is pretty... it's indicative of what's going to be in the film. If they like the trailer, and you think they can handle that, it's the right thing for them. The problem is, when you go too young, you lose the older audience. Lucas always said he was going for eight-year-olds for the Star Wars movies. You start going too young, you lose the adults, you lose the teenagers, and I wanted to make a movie for everybody, as I think Walt did. We'll see, we'll see what happens here.

Thinking about the blocking and the camerawork in the film, the shot choices aren't that different from your past work, especially during walk-and-talk scenes. Despite having all these tools at your disposal, were you still approaching scenes, visually, similarly to how you did on your other films?

Thinking about the blocking and the camerawork in the film, the shot choices aren't that different from your past work, especially during walk-and-talk scenes. Despite having all these tools at your disposal, were you still approaching scenes, visually, similarly to how you did on your other films?

Yeah, I think just because you could do anything doesn't mean that you should do everything, and I learned that from Iron Man. When we filmed Iron Man flying, you just didn't throw a virtual camera anywhere. That works sometimes, by the way. It works and it's fun when [Sam] Raimi does it with Spider-Man, but for Iron Man I wanted to feel like you were looking at a real movie being filmed. If Iron Man was flying, you're filming him off of a plane. We would look at photography from movies like Top Gun to determine what type of lenses we would use to shoot Iron Man.

In this one, we really tried to make it feel like they were real cameras on real rigs, so that people would assume that we just went off to the jungle and we were shooting real animals. When they talk or do things that they don't normally do, you start to realize that you're seeing something quite different. I think we tried to exercise a lot of restraint.

That opening shot takes its time to really let you get into the environment. Did you and [cinematographer] Bill Pope have a lot of conversations about how you wanted to invite audiences into this world?

A lot. I mean, that was everything. That was everything we did. A part of what was good about Bill Pope is... A cinematographer on a film like this, they determine what their role is. They could come in and just film the live-action stuff, which would be fine and help set the mood. In the case of Bill, he was there for all of the motion-capture sequencing, motion-captured the whole film before we ever filmed anything. He worked with MotionBuilder, on the photon, and learned all these technologies. How to set the lights, how to adjust the environment.

By the same token, our production designers were involved in that aspect. My editor, Mark Livolsi, was involved with... Because it was so non-linear, you go back and forth. We remade the movie over and over again. Sometimes the editor was asking for a shot, or the cinematographer was suggesting a sequence of cuts for the way the shot is laid out. What was kind of fun, and thankfully everybody really embraced this, was people had contributed in an interdisciplinary way, with other areas where they normally aren't weighing in. I think it made for a really good collaboration.

Is there a certain level of anxiety or fear of waiting a year or two to see how a shot comes together?

Yeah, I bought a bunch of ships in a bottle on eBay. I kept them all around our offices as a reminder that a ship in a bottle doesn't look like anything until the very end. Fortunately, there were a lot of people who had worked on Avatar who were working on this who said that it looked like a video game up until the last few months. There is a bit of a leap of faith, but you do see moments in tests that give you an indication of it. Really, what happens then is that it blows fresh wind into your sails, because every time you're looking at an effects review, it's like opening up Christmas presents. Each shot, when you see it for the first time, you have to watch it three or four times before you could even talk because it's so overwhelming to see. Part of what's fun about this is the audiences are going to be seeing all of those shots for the first time strung together.

There is an underlying magical element to this type of filmmaking that, I think, makes a case for people to come to the movie theater and see this thing on the big screen, because so much has gone into it, so many people have poured so much into it that it really, I feel, adds an energy that I still really connect with, because I just haven't seen it that many times in it's finished form. When it all comes together, with the music and the sound, and we were trying to channel Fantasound, which Walt Disney had been working on on Fantasia, and had been using some of those techniques in this. Of course, the color-timing and the finished effects and the performances all coming together. It still feels like a fresh new thing that I'm getting to see, that I'm not growing tired of as I would normally on a film at this point.

Discussing making a case for people to come out to the theater is timely, with the conversation surrounding the Screening Room. What are your thoughts on that?

I think there's been talk of technology eliminating film for a long time. It first really became part of the conversation when television was becoming ubiquitous. The role of film is changing. When I say film, I should say theatrical presentation of that format. It used to be a monopoly. If you wanted to see content, you had to go to the movie theater. Now, you're seeing great content in a great format at home, and you're seeing it on your computer. People are generating their own content, there's peer to peer, so I think you have to make a case for people to come to the movies.

What's been nice, even though mid-budget movies have migrated to the small screen, you're still getting good content, you're just not seeing it in the theatrical environment. You get low-budget stuff, like comedies, on the big screen. It's been spectacle-oriented film that's translated to a global audience and to all ages. People will go to the movie theater to see movies that are based in spectacle.

What I think is interesting, now, and Jungle Book is an example of it, there are other types of movies that people are willing to go to the movie theaters to see. You still have to make it something that's exciting and interesting and something that you will only get the full experience when you're seeing it wall-sized, and with a group of people, so that you're connecting with it together. I think there is a communal experience to movies that does get lost when you're watching it at home. I think it depends what the movie is, I think that there's an inevitable migration from the theater to the home. I think our job, as filmmakers, is to keep the experience of seeing it in the theater robust enough that you can compete with these other ways of consuming content.

***

The Jungle Book opens in theaters April 15th.