How Did This Get Made: A Conversation With Steve Binder, Director Of The Star Wars Holiday Special

What does the infamous Star Wars Holiday Special have to do with improving race relations and Elvis getting his groove back? Steve Binder. So this holiday season, I sat down with the legendary director to talk about Wookiees, Hound Dogs and some of the other highlights from his career.

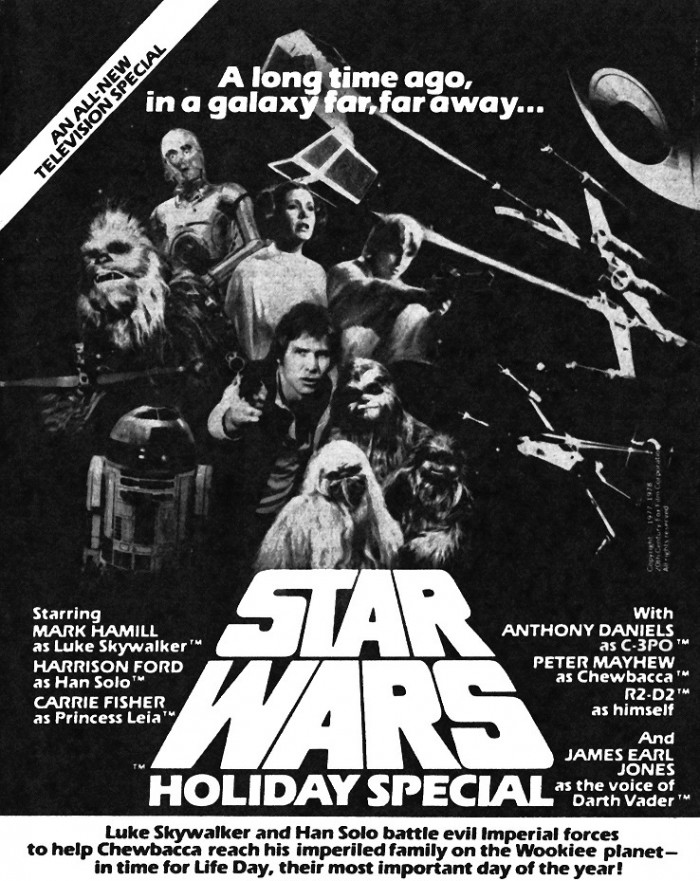

For anyone who thinks Jar Jar Binks is the most despised thing in the Star Wars universe, I've got some bad news for you. The runaway victor in that category is the two-hour Star Wars Holiday Special that aired on CBS in November, 1978. Even George Lucas hates it, having famously once said at a Star Wars convention that, "If I had the time and a sledgehammer, I would track down every copy of that show and smash it." But before Lucas felt this way—before the Holiday Special ever went into production—he and his team at Lucasfilm thought there was a great opportunity here. One year prior, Star Wars had first hit theaters and broken just about every box office record on the planet. And one-and-a-half years later, The Empire Strikes Back would be released. So, from their perspective, the Holiday Special represented a great opportunity to whet some appetites in the meantime and, of course, sell some toys. It's no coincidence that the Star Wars Holiday Special premiered a week before Black Friday. Nor is it a coincidence that Kenner had been developing a new line of action figures based on the Wookiees who appeared in the special. [Nor is it, one can assume, a coincidence that a day after the Holiday Special, Saturday Night Live's guest host that evening was none other than Carrie Fisher] In light of this information, it's easy to take a cynical point of view. But then again, selling merchandise and appealing to children has always been central to life in the Star Wars universe. So it seems much more likely that the Star Wars Holiday Special began with the best of intentions and then just spiraled out of control. And when it did, spiraling to the point that CBS considered pulling the plug, the project was rescued by a legendary variety show director by the name of Steve Binder.So this past weekend, I sat down with Binder to find out what that experience like and also learn a bit about how he'd obtained that "legendary" moniker. Below is a copy of our conversation. Merry Christmas from myself and the How Did This Get Made? gang who, once again, have put out a podcast episode that's funnier and more enjoyable than most of the movies I've ever seen.

For anyone who thinks Jar Jar Binks is the most despised thing in the Star Wars universe, I've got some bad news for you. The runaway victor in that category is the two-hour Star Wars Holiday Special that aired on CBS in November, 1978. Even George Lucas hates it, having famously once said at a Star Wars convention that, "If I had the time and a sledgehammer, I would track down every copy of that show and smash it." But before Lucas felt this way—before the Holiday Special ever went into production—he and his team at Lucasfilm thought there was a great opportunity here. One year prior, Star Wars had first hit theaters and broken just about every box office record on the planet. And one-and-a-half years later, The Empire Strikes Back would be released. So, from their perspective, the Holiday Special represented a great opportunity to whet some appetites in the meantime and, of course, sell some toys. It's no coincidence that the Star Wars Holiday Special premiered a week before Black Friday. Nor is it a coincidence that Kenner had been developing a new line of action figures based on the Wookiees who appeared in the special. [Nor is it, one can assume, a coincidence that a day after the Holiday Special, Saturday Night Live's guest host that evening was none other than Carrie Fisher] In light of this information, it's easy to take a cynical point of view. But then again, selling merchandise and appealing to children has always been central to life in the Star Wars universe. So it seems much more likely that the Star Wars Holiday Special began with the best of intentions and then just spiraled out of control. And when it did, spiraling to the point that CBS considered pulling the plug, the project was rescued by a legendary variety show director by the name of Steve Binder.So this past weekend, I sat down with Binder to find out what that experience like and also learn a bit about how he'd obtained that "legendary" moniker. Below is a copy of our conversation. Merry Christmas from myself and the How Did This Get Made? gang who, once again, have put out a podcast episode that's funnier and more enjoyable than most of the movies I've ever seen.

Part 1: “This Was Not Going to be Star Wars 2”

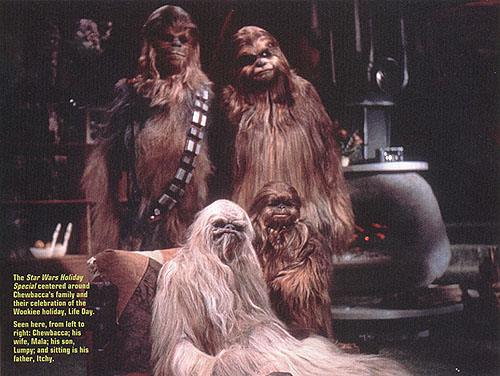

Blake Harris: I'd love to start off by hearing about the first time you ever even heard the words "Star Wars Holiday Special?"Steve Binder: I got a call from Gary Smith, one of the executive producers, to see if I was available. At this point, the production had already been going for a week or had shut down. They'd run out of money. They were spending way, way over budget. And evidently there were lots of problems.Blake Harris: What kind of problems?Steve Binder: Well, I went out to Warner Bros. where they were shooting on a big stage. And they had built the Chewbacca family home, which was a phenomenal set. But it was a full, 360-degree set.Blake Harris: You mean that unlike, say, a sitcom where an "apartment" is really just three walls and a wide opening for cameras and crew, this was essentially a self-contained—albeit it phenomenal—set?Steve Binder: Right. I remember walking out there and saying, "No wonder you're having problems. You have a 360 set with multiple cameras!" And there was no way they'd be able to get these cameras in to shoot. Another concern was the opening itself. Where there's no dialogue and it's just all subtitles with the Wookiees.Blake Harris: That's not quite a promising start. So what was it about the project that attracted you? Were you a big fan of the movie?Steve Binder: I went to see the original and I loved the production value. But to be honest with you, I'm not a great science fiction fan. I love heartwarming stories. I'm a sucker for a good love story.Blake Harris: This was at least more family-oriented. Less space opera.Steve Binder: So I said yes and they FedExed me a bible, basically, on the Chewbacca family. A pre-life that George Lucas had written. I think having someone as creative as George writing the life of the Chewbacca family, taking the time to develop his characters and give them a full three-dimensional life before you even get to the beginning of the story in the special; that was fantastic. And I had obviously no input whatsoever on changing anything. I was just a fireman—I was there to get it done—if CBS decided to move forward at that point. Because they were all talking about pulling the plug. But they decided to go forward and I think the public wasn't prepared in the television advertising etcetera for what this was. And I think that was the huge mistake. This was not going to be Star Wars 2. This was a variety special focused on selling toys for George's merchandising deal.Blake Harris: I want to hear more about all of that later, but first I can't help but wonder: why you? And I mean that respectfully. When the production was in trouble, why were you the "fireman" they turned to try and save the day? I guess what I'm really asking is this: how did you become the go-to guy for variety shows?

Part 2: In Which the Prospect of Pretty Girls Reveals a New Path

Steve Binder: It's kind of funny. When I was a little kid, I spent a lot of time in our family's one bathroom fantasizing and pretending. I was a fighter pilot in World War II. I was a star football player for a college team. I listened to radio a whole lot and I was able to determine what my heroes and villains looked like and how they acted. And I think one of the great tragedies of television is that all those things that require your imagination have kind of been eliminated by, you know, casting directors. So I think radio was a great opportunity for me to expand my imagination.Blake Harris: So growing up, did you always know you wanted to be in the entertainment business?Steve Binder: I was raised in Los Angeles, in the heart of Hollywood. But show business, I just never dreamed about getting into that business, you know? All I knew was that I wanted to do something to make my parents proud 'cause I was fortunate to come from a really solid middle-class home. My parents really struggled very hard to send my sister and myself to college. And, you know, we never felt we lacked anything in our childhood. So I wasn't sure what I wanted to do and when I went to University of Southern California, I actually started off as a premed student.Blake Harris: Ha! How did you switch from medicine to entertainment?Steve Binder: Well, when I went to USC, I did double duties: I worked at my Dad's gas station in downtown Los Angeles and then I got a job announcing for KUSC radio on campus. That's what really whet my appetite. Because I was basically, you know, pretty introverted on the outside and then when I got in front of that microphone I found this other personality coming out where I had no fear.Not long after discovering this passion, Binder was drafted into the military. Stationed in Austria and Germany during the Korean War, he became an announcer on the American Forces Network. After Binder returned home, he was hoping to start a career in radio. But a high school friend wound up leading him in a slightly different direction. Steve Binder: He was an assistant assistant editor at Paramount on Star Trek. And he suggested that if I wanted to meet some pretty girls, I should get a job at one of the studios. So I got a job at KABC, which was the ABC affiliate in Los Angeles. That would take an hour to explain, but literally in about 6 weeks I was directing the Soupy Sales Show. that set me on a path and I was kind of on my way.Blake Harris: Did you know right away that this was the career for you?Steve Binder: I mean, even when I had gotten the Steve Allen show, I wasn't sure this was going to be my life's work. I just thought this was a lot of fun and I might as well take advantage of it while the opportunity was there. Doing the Steve Allen Show, five nights a week and 90 minutes a night, I just kind of met everybody in show business during the couple years I was there. And as a result I realized that while all my friends were waiting to get off work to have some fun, I was having fun working and I thought: this is a great profession. So that's what got me into it. But I've had a very eclectic career. I never really wanted to do just one thing. I always chose to have a beginning, middle and end, and then start it all over again on the next project.Blake Harris: One of those next projects that really piqued my interest was the Petula Clark special [which aired on NBC in April 1968]. Can you tell me a little bit about that and the controversy that ensued over "the touch?"

Part 3: On the Path of Glory

Steve Binder: The Petula Clark Special was incredibly unique because—without boring you with a long, long story—NBC had made a deal with Nancy Sinatra's agents when she had the hit record These Boots Were Made for Walking. And I got the call from her agency saying we're in a lot of trouble because Nancy left the special that was sold to Plymouth Cars, a division of General Motors, and she got a better deal from a Cola company. I think RC Cola. So she did that, and the agency needed to replace her with another star that Plymouth would accept.Blake Harris: Petula Clark?Steve Binder: Yeah, but after they all agreed—the network, the sponsor, everyone—that Petula would replace Nancy, they assigned Greg Garrison, the director/producer of The Dean Martin Show. But evidently, Petula and Greg didn't hit it off so she went back to Europe and the agency was stuck with having sold this show but now not having a star for it. So I got a call from Petula's agents and they asked if I would go to Megève, Switzerland, to have lunch with Petula to talk her into coming back to America and doing the special. So I did.Blake Harris: And what was that lunch like?Steve Binder: Well before I went out there, I had been given a rundown of what Greg Garrison and some agents at GAC [General Artists Corporation] had put together for the special. I read it and thought: this is just a compilation of other specials. A segment here, a segment there, so I didn't want to do that. Because I had decided early on that I wanted to do specials that were really special. In other words, if for some reason Petula Clark or Leslie Uggams or whoever was starring in the special got sick, I couldn't just say, "let's get someone else to do it," because each show was tailor made for them and them alone. So I literally conceived Petula's show on the way flying to Europe and when I had lunch with Petula I pitched her what I wanted to do and she came back to America and we did it.Blake Harris: And how did Harry Belafonte become involved?Steve Binder: I was a great, great, fan of Belafonte so I booked him to do the Petula Clark Special. I was excited and so was the agent representing Plymouth (our sponsor). At first. But the next thing I know, I get a phone call saying I have to get rid of him. So I say, "What are you talking about?" And the agent says, "Well, Doyle Lott [the advertising manager of Chrysler's Plymouth division] doesn't want to have a black man on the special." I say, "You've got to be kidding." "No" he tells me. "On the record, Lott's saying Belafonte doesn't have any hit show any more, he's not selling records and so that's his justification for not wanting him on the special. But off the record I'm telling you the guy's a racist and doesn't want a black man on the show."Blake Harris: Wow.Steve Binder: It was 1968 and racism still raged on, especially on network television in prime time. So I said, "Well, if that's the case, then I'm gonna go nationally and quote you and what you just said." And he said to wait a minute and he'd call me right back. Five minutes later I get a call from someone else at the agency. He says, "My name is Colgan Schlank and I'm replacing the guy you just spoke to and we're going to work this out." Eventually I had to fly out to Detroit Michigan to meet the head of Plymouth Cars. I had to go there to tell him what we were doing because the rep from Plymouth wanted to pull the plug and cancel the show. After speaking with him, he asks me if Petula was happy with the special and was I happy with the special and when I answered yes to both he said, "Then I don't think we should interfere. You go back to Hollywood and let's do it."Blake Harris: While you were out there, did you also meet with that guy Doyle Lott?Steve Binder: [laughing] He came up to me right after the meeting, shakes my hand and says, "I'll see you at the Emmy Awards."Blake Harris: But I guess you saw him beforehand. I read that he was at the taping. Tell me about what happened there.Steve Binder: On the Path of Glory was the name of the song. that Belafonte and Petula would be dueting. It was a song Petula had written about mothers sending their sons and daughters off to battle and how, years later, it's really just a piece of land they fought for and everybody kind of forgets what happens there. So that was the song they did together and initially I staged it with her upstage of Harry. I loved the shot—with her over his shoulder—but the chemistry wasn't there. Because they were separated. So after doing about five or six takes, I finally said the hell with the shot and told Petula, "Next time, don't stand behind Harry. Just go up alongside him. And shoulder to shoulder." And that's when all the magic happened. That's when I looked at the close-up on cameras and there were tears coming out of her eyes and I looked at the close-up and there were tears coming out of Harry's eyes. And then Petula reached over and touched Harry on the forearm and all hell broke loose.Blake Harris: In what sense?Steve Binder: The sponsors are freaking out in the green room. A white woman and a black man touching on national television! And I start getting phone calls from Newsweek and Time magazine wanting to come down the studio.Blake Harris: How did NBC react?Steve Binder: Well, NBC phones me in the control room and says, "We don't know what the hell's going on in the control room but we just want you to know that we're behind you." Which is just a great phone call to get from the network. Really. But having enough experience in this business, I realized that if I wanted to make sure this take aired then I had to get rid of those five or six other takes I had done previously. The ones where they didn't touch. So I immediately went down to the editing room in the basement of NBC and told the editor to destroy all the other takes. And that's how it made it to air. That's a moment that I'm really proud of. And then right after that, that's when I did the Elvis Special.

Part 4: Elvis Through the Keyhole

Steve Binder: On Day One, when I first met Elvis, he asked me what I thought of his record career and I told him I thought it was in the toilet.Blake Harris: Wait. One of the first things you said to Elvis Presley was that his career was in the toilet?Steve Binder: I think everybody in life needs a Jiminy Cricket on their shoulder. Telling them the truth. And you know what Elvis said to me? He said, "You're the first person with the guts to tell me the truth." So I think we just hit it off more as friends than as him being the star and me being his director and producer.Blake Harris: Given that his career was "in the toilet," what was he like to work with at that time?Steve Binder: Well, I knew how insecure he was. How he didn't really want to do this. On that first day we met, he said that other than The Ed Sullivan Show, he hated doing television. He hated doing The Steve Allen Show and The Milton Berle Show because, as he said, "they just made fun of me. They made me dress in tuxedos and on one of the shows put a real live hound dog in front of me." They laughed at him. It wasn't his turf, he said. So I asked what was his turf. And he said making records. So I said, "Okay, you make a record and I'll put the pictures to it." He told me later on that those were the magic words. That he relaxed and said okay I trust you. And I was a little nervous because he never said no to anything. Once we pitched him the show, he said, "I love it all let's do it." We were off and running.Blake Harris: So you earned his trust, which I'm sure was critical, but I'm wondering if you ever feel like he was happy to be there?Steve Binder: Well, before we moved over to NBC, Elvis used to come over to my office on Sunset Boulevard to rehearse. He'd come over with his whole entourage. And one day earlier on, I asked Elvis what he thought would happen if he walked out alone on Sunset. He looked at me and said, "What do you mean?" And I said, "I want to know what you think would happen if you walked out onto Sunset Boulevard right now? Are they going to tear your clothes off? Are they going to mob you?" He was amused by that question, but didn't answer. Instead, he asked me what I thought would happen and I said, "Nothing," and we dropped the subject and moved on. So anyway, a few days later he walks into my office with his entourage behind him and says, "Okay, let's go." "Go where?" I said. And he says, "We're going downstairs on Sunset Boulevard to test your theory." Okay. So the whole entourage starts to pile out of the office, but then Elvis says, "No, no. You all stay here. I'm going downstairs to see what happens with Steve alone. You guys can watch from the window."Blake Harris: Ha!Steve Binder: So we went down and we walked out on Sunset at about four in the afternoon. Our office building was right next to this big retail record store called Tower Records, so there were a lot of young kids walking on the street and going in to buy records. Elvis and myself just stood there and started doing small talk to each other. Pretty soon, kids were bumping into us and we'd have to move for them. And not one of those kids realized they were bumping into Elvis Presley. So after about a minute or two of that, Elvis wanted to get some attention drawn to himself so he started waving to girls who were driving by in cars and stuff like that. But they didn't pay any attention to him. And after about five minutes, I knew he was uncomfortable and he said, "You proved your point, Steve. Let's go upstairs." So we went back up.Blake Harris: I mean, I know his career was waning. But really? That bad?Steve Binder: Well, what I never told Elvis was that the real reason they ignored him was because they didn't know it was him. The truth of the matter was that there were so many characters in Hollywood in those days who were trying to look like Elvis that people probably thought he was just another a lookalike. Probably if we'd had a sign saying Elvis Presley was here, he really would have been mobbed and they would have torn his clothes off. But I never told him that. Ever. I just kept that to myself. But when we went upstairs, there was an attitude change in him and I sensed he trusted my judgment even more.Blake Harris: Wow. That's amazing and hilarious and sad and beautiful. And what about the show itself? You said earlier that you wanted each special to feel, you know, special. So what was your approach to accomplishing that here?Steve Binder: Well, when we moved over to NBC in Burbank, Elvis lived in his dressing room. He never went home during the entire week that we were in production. And that's where I got the idea for the improv. Those jam sessions and acoustic sessions. Because after we'd finish a full day—of rehearsals and shooting various segments—he would go into his dressing room bedroom and start jamming with anybody who happened to be hanging around. Until three or four in the morning, Elvis would play songs and tell all kinds of humorous stories, reminiscing about the old days. And, you know, that was the magic. Even though I was in the dressing room with him, to me it felt like looking through the keyhole of a door and seeing something inside that you're not supposed to see. His hair all messed up, you can see the sweat on his face and he's just talking and singing and having a ball. For me, it was watching a man really re-discovering himself. That's what the guts of his comeback was. And so that's what we ended up recreating on stage.Blake Harris: That special was obviously instrumental in reinvigorating his career. I'm sure he must have been quite grateful. Did the two of you continue to stay in touch?Steve Binder: The very last time I saw Elvis was a get together we had among ourselves. Seven of us, my whole gang: Gene McAvoy, our art director. Our writers: Allan [Blye] and Chris [Bearde]. Bill Belew, the costume designer and Earl Brown, who wrote "If I can Dream" and was our choral director. These were the guys I generally worked with and we were all gonna meet up at Bill Belew's apartment in Hollywood for some pizza and beer. I asked Elvis if he wanted to come and he said, "No, I couldn't do that." But then I screened the show for him twice and he changed his mind. So after we were done for the day, Elvis and I got into my yellow Ford convertible. Behind us, his guys followed us over to Bill's apartment in Elvis big Lincoln Continental.Blake Harris: A nice little convoy on your way to some pizza and beer...Steve Binder: But we get to Bill's apartment and he's not there. None of the gang is there and nobody answers the phone. And so after about five minutes, Elvis says, "I should go." So I walk him over to his Lincoln Continental and he asks his guys for a piece of paper and pencil. He scribbles down a number and whispers to me, "Steve, call me." Then a minute after Elvis leaves, up comes two cars and it's the whole gang. They had been buying the pizza and the beer and stuff. What a missed opportunity. But that was the way it was. And when I called the number to talk to him, Colonel Parker [Presley's notoriously ruthless manager] had stepped in and I was persona non grata in the Elvis world. I wasn't allowed to see him or anything. So the last time I ever saw Elvis was when we drove to Bill's house in Hollywood.Blake Harris: Well, that's kind of an unfortunate way for your relationship to end. But I can now safely say that I understand why you got the call from Gary Smith about doing the Star Wars Holiday Special. You had mentioned earlier some of the challenges going on, so let's talk about what happened after you actually started...

Part 5: The Good Old Days

Steve Binder: The first decision I made was to cut into the set and remove one of the walls so we could get all the equipment in there. Inside the Wookiee environment, which was probably what 99% of their problem was before I ever got involved. And then I basically just prepped every night and took it one scene at a time. From my standpoint, as a director and producer, it was a totally positive experience for me. I loved meeting and working with everybody. And I think we did it pretty well under the circumstances.Blake Harris: Tell me a bit about those circumstances. Any memorable difficulties?Steve Binder: Well, one issue to begin with was the fact that the Wookiee costumes were so heavy! The actress who played the child, Patty Maloney, when we started she probably weighed only 80 or 90 pounds. And then she probably lost about 15 pounds from shooting the show. They [the Wookiees] could only shoot like 50 minutes of the hour and the other 10 minutes they had to have the heads off and be given oxygen off stage. So we didn't even have the principal cast available to shoot a full hour at a time!Blake Harris: [laughing]Steve Binder: And then there was the light ceremony at the end of the show. I was told there was no money left to build a set. So I had this huge airplane hangar film stage with extras and the entire cast of Star Wars in it and I just asked the art director if we at least had money to go out and buy a bunch of candles. Which is what we did. We bought up every candle within the vicinity of Warner Brothers that was available.Blake Harris: Was that kind of stuff frustrating for you, creatively?Steve Binder: I thought that turned out well in my opinion. For the most part, I felt that way about everything we did. I mean, I didn't walk away thinking this was a disaster or anything. I had the opposite feeling. I was glad I did it and I learned a lot and got to work with some of the best technical people in the business.Blake Harris: What about George Lucas? What was your relationship with him during the production?Steve Binder: I never saw him or even received a phone call from him. He was never on set at all. But he came up with the story, and supervised the script by the writers they brought in [Pat Proft, Leonard Ripps, Bruce Vilanch, Rod Warren and Mitzie Welch]. And he approved it. I think he distanced himself when he didn't get great reviews. I mean, to sort of disassociate from it when he was the whole force behind the project; that's disappointing. And saying, you know, he wanted to buy the negative and get it off the market and so forth. Which was kind of ironic because he's the one—before I ever entered the picture—who wrote the script and gave it the green light from his end. With the goal of selling a lot of toys. But I think it just goes back to what I said earlier: they failed to tell the public exactly what it was. This was not Star Wars 2 and I know a lot of fans were really disappointed. With expectations so high and here you had Harvey Korman doing a cooking parody of Julia Child in a scene. You had Diahann Carroll singing a sexy song in it and you had Jefferson Starship trying to do a hologram sequence and so forth. And the story itself was pretty weak. But I'm glad I did it and I learned a lot. And I can honestly say that I've never done a show where I didn't learn something from someone.Blake Harris: Well on that note, let me just ask you one more question. You've obviously learned a lot over the years. And, of course, the entertainment landscape has changed a lot over the time, but I was wondering what advice you would give to someone who, like you, wanted to make specials that were special? Someone who was interested in producing or directing variety shows?Steve Binder: I think it would behoove any student of variety productions to go back and look at the history. Whether it's the Streisand specials, the Liza Minnelli specials, or even going back to the Milton Berle's and Perry Como's series. I think it's important that these young directors study those shows so they don't begin their careers just thinking that all that's on television in variety is Beverly Hills Housewives or the Kardashians. I mean, when I started there were only three networks. That was it. Now you have 500 choices of what to look at. But if you sit there and go through the 500 choices there's not a lot to watch that's new and fresh and exciting. So television has to reinvent itself. And it will. I'm not one who believes in the "good old days." I think the good old days are ahead of us. It's a young world, you know?To read more about the ill-fated Star Wars Holiday Special, I recommend the following: