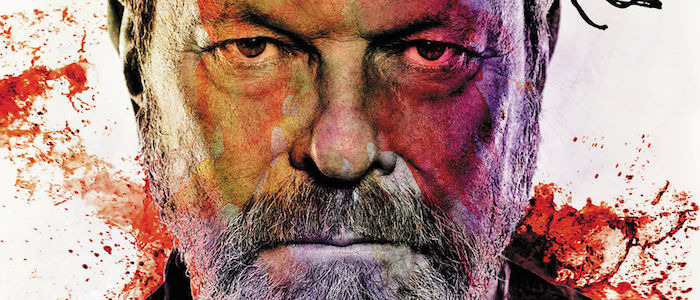

Notes On The Fascinatingly Mundane Origin Story Of Terry Gilliam

Someone who cracks open Terry Gilliam's Gilliamesque hoping for a comprehensive and complete portrait of the man's career may be disappointed. The memoir from the director of Brazil, Time Bandits, and The Fisher King is akin to having a nice, long sit-down with an eccentric uncle who stories to tell and grudges to share. It's a little rambling and it occasionally leaves big questions unanswered, but at the same time, of course it is. This is Terry Gilliam after all. The guy who directed The Adventures of Baron Munchausen. He has a yarn to spin and he's going to spin it his way.

Gilliamesque: A Pre-posthumous Memoir is captivating reading for anyone with an interest in the filmmaker, who began his career as the Monty Python troupe's animator and eventually segued into making some of the best and most interesting movies of his time. Gilliam dives deep into his childhood in Minnesota, his adolescence in California, and his attempts to make it big in New York City and London. The book is halfway over before he even gets to the Monty Python's Flying Circus.

And yet that first half paints a detailed portrait of an artist to be. You can see the elements that later become vital components of Gilliam's career surface throughout his early life in surprising, funny, and occasionally depressing ways. Let's run down a few of them, shall we?

It you want to read Gilliam's stories about making his biggest movies or listen to him throw some pretty serious shade on Johnny Depp and Graham Chapman, you'll need to pick up a copy of Gilliamesque yourself. If you think you're the kind of person who will enjoy it, you probably will. It's a beautifully designed book. All we're going to do here is dive into some of Mr. Gilliam's stories from the first half of his book, the first 30 years of his life or so, to examine how his unique voice was shaped by his life experiences. Cool? Cool. Let's do this.

The Mundane Adventures of Terry Gilliam

One of the most interesting aspects of Gilliamesque is just how stable Gilliam's life and upbringing is. Early in the book, he bemoans having a happy childhood, joking that he never received the scars that define many artists:

That's what kills me; I've always wanted the scars, but I just don't have them. In fact, that's probably why I had to go into film-making – to acquire the deep emotional and spiritual wounds which my shockingly happy childhood had so callously denied me.

That seems a little odd for a filmmaker who would eventually go on to make vicious satires like Brazil, nasty and childhood-skewering fantasies like Time Bandits, but it makes sense. Gilliam's happy, suburban youth seems to have given him the observational powers of an outsider. It's no wonder so many of his movies are about the power of imagination – it's what powers him. He has to riff on what's inside his own head and the stories he knows and the movies he's watched.

It may also come as surprise that the director of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas was not a heavy drug user. He blames his age for this – he was a little older than his LSD-using friends and kept his distance after seeing them endure a few bad trips. Gilliam is self-deprecating about his lack of experience with controlled substances:

[The biography of Harry Nilsson] I was reading recently showed him falling into a spiral of drink and drugs that felt like a direct by-product of his achievements. That's why I've worked so hard over the years not to become too consistently successful – because it's safer that way.

This may explain why his take on Hunter S. Thompson's book is an intentionally off-putting black comedy – he's seen people indulge in this kind of behavior while avoiding it himself. Another filmmaker may have made slightly more sympathetic movie.

The Bible and Mad Magazine

Gilliam isn't shy about being non-religious, but he's glad he was raised in a religious household, mainly because he likes knowing the stories of the Bible. He even laments his children's secular upbringing, saying that knowing the basic tenets of a religion make you a better storyteller and audience:

It's not necessarily a question of having a reverential attitude. What's interesting is sharing a culture that has grown out of those tales, because it's easier to have fun with things when everyone understands what the references are.

Religion is rarely a huge theme in Gilliam's work, but his childhood Christianity can be felt in the way he tells stories with a broad brush and the way his movies riff on imagery and ideas that reverberate across all cultures. Gilliam is obsessed with storytelling as a concept and the Bible is the core around which most modern narrative orbit.

Still, the first thing that seems to have really shaken Gilliam up, the publication that set him on the path to becoming an artist, is Mad Magazine. It's here that he learned his basic comic chops:

The first lesson I learned from Mad comics was that one of the most effective ways of making a comedic point is to take a well-known character with certain widely accepted attributes, and turn them on their head or use them in illicit ways.

The Bible taught Gilliam how to tell a story and Mad taught him how to subvert it. You can feel the influence of both in films like The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, which takes classical storytelling structure and takes the piss out of it.

Hiding in Plain Sight

Gilliam's "family" movies probably couldn't get made today. They're too dark, too weird, and too unpleasant. He makes movies for kids under the assumption that kids want to be challenged and that their parents want them to have a memorable, visceral experience. Remember the ending of Time Bandits?

It turns out that Gilliam may have absorbed his idea of what a children's movie should be during his college years. Students would gather together to watch children's TV shows together because they realized the concepts being snuck into these seemingly innocent shows were fare more subversive and interesting than anything being made for adults:

...one reasons students tend to like watching kids' TV shows is probably because even though you know you're technically too old for them, they offer you a link back to the reassuring world of childhood ... It wasn't just televisual comfort food either – kids' shows often tended to be the most interesting because the adults at the networks weren't likely to be paying attention, so you could get away with murder...

Some of Gilliam's movies feel like he wants to recreate this scenario for a new audience. An innocent exterior masks a dark center. A smile masks a dagger.

Chaos Is a Way of Life

During one summer break from college, Gilliam took a job directing children's theater and his production of Alice in Wonderland is awfully ominous for anyone who knows his future Hollywood career. The overambitious production was canceled at the last minute and he writes that it still haunts him fifty years later:

I ended up pulling the plug in the final week before the show [...] The scars run deep... even unto today when I often wake from a dream of the fear of repeat failure on whatever my current project might be.

It's no secret that Gilliam is, well, kind of cursed. His tortured, long-in-development The Man Who Killed Quixote is the most famous example of one of his movies falling apart around him, but it's not the only calamity he's faced. Disaster seems to follow Gilliam wherever he goes. Sometimes, this chaos is channeled into his films. His best movies often feel unhinged, like they're ready to fly off the rails at any moment. The fact that Brazil and Twelve Monkeys and Baron Munchausen stay on track throughout the chaos is why they're remarkable.

Gilliam shares other stories of chaos, but some of them are actually funny and not heartbreaking. Like the time he decided that the motorcycle that was making his journey across Europe a living hell needed to go:

By now I'd become obsessed with this bike, which must have been prophetically possessed by the spirit of Don Quixote, because it seemed to be doing everything it could to humiliate me [...] Once I reached the next youth hostel after Barcelona I just said, 'That's it – this bike must die.'

He then gathered a crowd, took his ill-fated vehicle to a field, and lit it on fire. Unfortunately, the local authorities thought the flames were the result of a smuggling operation and Gilliam was forced to flee the area. This escalation from innocent bad idea to a serious police incident feels like it was torn out of one of his movies.

A Problem With Authority

Almost every Gilliam film treats institutions and authoritative figures with distrust at best. The system, his filmography says, is broken. Break free. Do your own thing.

Gilliam's rebel instincts kicked in early, when he found himself alienated by his fellow students in the New York City-based film classes he was taking while working at Help! magazine. His public image as an artist bucking the establishment begins here, for better and worse:

From then on, I knew all I needed to do as far as film studies was concerned was go to the movies – that's always been enough for me – get myself a camera, write some little stories and get together with some friends to shoot them.

Naturally, when he started dipping his toe into animation a few years later (and the rest is history, etc.), the chief targets of his comedy were anyone or anything that could potentially cause offense. The rest of Gilliamesque tracks his constant battle with censors and producers and movie studios. The root of all those creative battles, which have defined Gilliam's public persona in a huge way begin here:

I'd find people in serious situations – soldiers in war-time, politicians on the campaign trail – and liberate them by putting them in a dress or making them do something ridiculous. The more solemn and even humorless the original character, the more potentially funny he or she was.

Learning From the Masters

Living in New York allowed Gilliam to fully explore the arthouse and foreign film landscapes. He recounts devouring everything, literally walking out of the theater with his horizons widened:

One of the themes of my New York years was the wonder of discovering foreign films – whether they be Ealing comedies, Kurosawa or Bunuel – and realizing that not everyone in front of the camera had to look like Rock Hudson or Doris Day [...] I'd devour Chaplin retrospectives, and come out of Eisenstein films in a reverie thinking 'Wow, angles.'

However, he dedicates almost an entire page to the work of Richard Lester, who was still a few years away from directing The Beatles in A Hard Day's Night when Gilliam first discovered his short films. Seeing what he accomplished on such small budgets changed the way Gilliam thought about filmmaking:

I'd never seen anything that felt so free. Lester's frenetic and fun-packed jeu d'esprit was a far cry from the more studied and sombre work coming out of New York's experimental scene of the early sixties.

You can see all of these influences in Gilliam's work, from the Akira Kurosawa-inspired samurai in Brazil to the Lester-esque sense of constant movement and energy that runs through his entire filmography. Hell, Brazil's original title, 1984 1/2, is a clever nod to both George Orwell and Federico Fellini. Gilliam has never been shy about paying homage to those who influenced him when he was still learning his trade.

Lessons From the Army

Like any young, fit man living in America in the '60s, Gilliam faced the draft and the possibility of being sent overseas to Vietnam. He managed to join the National Guard, avoiding combat but still getting a taste of the military lifestyle. Although he writes of his time in America's armed forces with frustration, you can see the germs of future comedic concepts and satiric points being formed:

Any inclination I might have to had (which was infinitesimal) to subsume myself entirely in the business of soldiering would certainly not survive the absurdities of basic training. I jut found the whole thing very hard to take seriously.

He writes about witnessing the broken bureaucracy of the United States government. His description of how the National Guard was run sounds like a deleted scene from Brazil:

Joseph Heller's Catch-22 was required reading for reluctant draftees like me. The book really captured the tragic foolishness of the whole business. [...] At this point you realized why so much of what you learn in the army is about projecting a coherent show of capable authority – because of the desperate need to conceal the reality of institutional incompetence.

Gilliam's odyssey through military life is ultimately whimsical and bizarre – he writes of traveling through Europe to escape his responsibilities, utilizing a network of fake correspondence to keep the government from knowing where he actually is. He managed what so many of his heroes failed to accomplish: he escaped the system and got away with it.

Disneyland and Disillusionment

Early in his book, Gilliam writes of frequently visiting and appreciating Disneyland, which opened when he was a teenager. The immaculately constructed fantasy lands of the park proved essential:

My imagination was ways stimulated by enclosed worlds with their own distinct hierarchies and sets of rules – whether that be the virtual reality of Disney's Tomorrowland, or the medical castles or Roman courts of the sword and sandal movie epics, which I loved just as much. Such well-defined social structure give you something to react against and take the piss out of, and I've always – and I still do this – tended to simplify the world into a series of nice, clear-cit oppositions, which I can mess around at the edges of.

This is the root of Gilliam's ability to take something he loves and rip it to pieces. He has an obvious fondness for medieval fantasy, so he tears into the genre with the ferocity that only a fan can muster in Monty Python and the Holy Grail and Jabberwocky. Of course Gilliam would love Disneyland – few directors put every inch of themselves into their world-building and Walt Disney's first theme park is the squeaky clean version of the detailed fantasias Gilliam would later accomplish in Brazil and Baron Munchausen.

However, Gilliam's falling-out with the park also feels like it was torn right out of one of his movies. When he returned to the park in 1967 as press to cover the opening of the Pirates of the Caribbean ride, he had a troublesome encounter:

When we arrived at the special place where the special people enter, we were told that the head of security would have to come down and vet my hair, because the guy on the gate who looked like an FBI agent had put in an alarm call. As I waited, I became aware – for the very first time – of the barbed wire around the entrance [...] The idea for Brazil was born out of several different moments of extreme alienation and this was definitely one of them.

This event, along with the Century City riot of July 1967 (where Gilliam and his girlfriend were assaulted by police), convinced him to take up residence in England for awhile. Two years later, Monty Python's Flying Circus premiered.

However, it's hard to imagine Gilliam, whose animations for the beloved series have become iconic, landing that job without every single thing above happening to him. Every artist is the result of a thousand experiences, of life lived in their own unique way. Gilliam isn't shy about his life, relationships, and trials in Gilliamesque and the result is an intimate and funny portrait of an utterly unique filmmaker.