'Jurassic World's Colin Trevorrow Addresses Gender Imbalance In Blockbuster Directing

Update: Colin Trevorrow wrote a response to this column, you can read it at the bottom of the second page of this post.

It's an unassailable fact that there are far, far fewer women directing big-budget studio blockbusters right now than there are men. Where people seem to disagree is on whether that's a problem (my vote is yes, but you knew that already), and if so, why the problem exists to begin with.

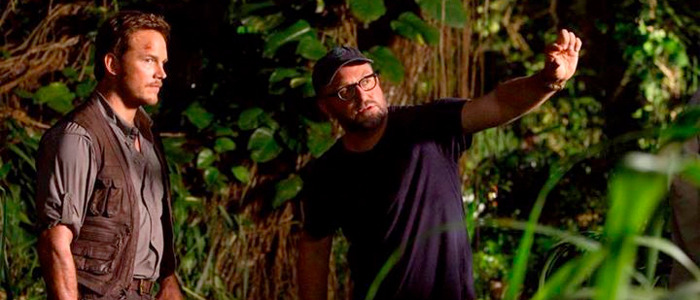

Recently, the director of one of those big-budget studio blockbusters — two, if you count his upcoming Star Wars film — ventured into the debate. Jurassic World and Episode IX's Colin Trevorrow sparked some debate by offering his thoughts on why there aren't more women making nine-figure spectacles, and whether that might change. Read the Colin Trevorrow female filmmakers comments after the jump.

What's the controversy?

Trevorrow addressed Hollywood's gender imbalance in response to a question from a fan (which in turn seems to be a follow-up to Trevorrow's earlier comments in an LA Times article):

Among the people who took issue with his response were actress / filmmaker Jaime King, a self-confessed Star Wars nerd and the wife of another notable Star Wars nerd, Fanboys helmer Kyle Newman. Trevorrow consequently clarified his comments:

The fact that Trevorrow addresses the question at all — and that he readily recognizes the imbalance in his industry — is a promising start. But his response falls apart somewhat when he scrambles to explain why there are fewer female filmmakers behind big-budget blockbusters like Jurassic World and Star Wars Episode IX, and he doesn't even try to suggest what might be done about it.

Trevorrow's explanation (and why it doesn't hold up)

According to Trevorrow, "Many of the top female directors in our industry are not interested in doing a piece of studio business for its own sake. These filmmakers have clear voices and stories to tell that don't necessarily involve superheroes or spaceships or dinosaurs." That's certainly true of some female filmmakers, such as Selma's Ava DuVernay, who recently turned down Marvel's Black Panther.

But Trevorrow wasn't a top male director when he got the Jurassic World gig. He was an up-and-comer with one minor indie hit (Safety Not Guaranteed) on his resume. The equivalent of Trevorrow (or Cop Car / Untitled Spider-Man Reboot director Jon Watts, or (500) Days of Summer / The Amazing Spider-Man director Marc Webb) isn't someone like Ava DuVernay, whose last film was nominated for Best Picture, or Kathryn Bigelow, who's already got a Best Director Oscar on her mantel.

Trevorrow's female counterparts — the women who are currently at the point in their careers that he was when he nabbed Jurassic World – are directors like Marielle Heller (Diary of a Teenage Girl), Jennifer Kent (The Babadook), and Maya Forbes (Infinitely Polar Bear). Last we heard, none of them were getting offered $200 million spectacles. Is it theoretically possible that the studios have approached some of these women, only to be shot down? Sure. But the fact that their names never crop up in the rumors or shortlists that circulate before any big announcement is telling.

The idea that female filmmakers are choosing not to make blockbusters due to their "very high levels of artistic and creative integrity" is a pleasant idea, but we don't have much reason to believe they're being offered these projects in the first place. It may also be the case that even once female directors are courted or hired, they're treated differently from their male colleagues — though Trevorrow doesn't address that notion, since it's somewhat outside the scope of the original question.

How Trevorrow is coming at this from the wrong angle

Trevorrow's heart seems to be in the right place. He insists there's "a sincere desire to correct this imbalance at the highest levels of our industry right now." It's hard not to feel for him when he admits the original question bums him out. "[I]t does make me feel terrible to be held up as a symptom of social injustice," he writes. "Nobody wants to be part of the problem." And it's worth pointing out he's already working with one very powerful female filmmaker — Lucasfilm's Kathleen Kennedy, who's the one that hired Trevorrow (and all those other guys) for Star Wars in the first place.

But Trevorrow is looking at the question wrong. The problem isn't that Trevorrow didn't deserve the chance to make Jurassic World. He obviously did, and he worked his ass off to make sure that was the case. It's that similarly talented, hard-working people who are similarly deserving of similar jobs aren't being considered those jobs. It's not a criticism of Trevorrow to say he would have been at a disadvantage for the Jurassic World gig if he were female. It's a criticism of the systems and biases that would have put Trevorrow at a disadvantage if he happened to be female.

What's next?

Trevorrow doesn't really offer any constructive ideas about how to fix the gender imbalance, which is understandable. If it were a simple problem with a solution so obvious it could be explained on Twitter, someone else would have solved it by now. But as a white male filmmaker (Hollywood's favorite kind, statistically speaking), Trevorrow in a position to help bring about change. He could use advocate for female colleagues, hire female crew members, or mentor female up-and-comers. He could look past people who remind him of himself, as Brad Bird movingly said of Trevorrow, to bring in people who offer a completely different perspective on the industry.

Maybe he already does all those things when we're not looking; I don't know his life. However, what is clear is that publicly, he's denying the real issue. Which, again, is not that the Ava DuVernays of the world are declining the Black Panthers, but rather that the Marielle Hellers aren't being offered the Star Wars: Episode Whatevers. And it's pretty hard to help solve a problem until you can first acknowledge it exists.

Response From Colin Trevorrow

Last night filmmaker Colin Trevorrow e-mailed the following response to this article to /Film editor Peter Sciretta. We present it without further comment:

The last thing I'd want to communicate is that I don't acknowledge this problem exists. I think the problem is glaring and obvious. And while it does make me a little uncomfortable to be held up as an example of everything that's wrong, this is an important dialogue to have, so let's have it.

Would I have been chosen to direct Jurassic World if I was a female filmmaker who had made one small film? I have no idea. I'd like to think that choice was based on the kind of story I told and the way I chose to tell it. But of course it's not that simple. There are centuries-old biases at work at every level, within all of us. And yes, it makes me feel shitty to be perceived as part of this problem, because it's an issue that matters so much to me. If I didn't care, I wouldn't talk about it in the first place.

I do stand by the idea that a great many people in the film industry want this to change. I have made attempts at every turn to help turn the tide, and I will continue to do it. When I got the script for Lucky Them, released last year, I advocated hard for my friend Megan Griffiths to direct. She did, and she made a wonderful film (see it please). On my next project, Book of Henry, nearly all of my department heads and producers are women. Will I give a female filmmaker the same chance Steven Spielberg gave me someday? Let's hope that when I do, it won't even be noteworthy. It will be the status quo.

I came home from New York tonight and saw my daughter again after a week away. This had come up earlier in the day, so it was on my mind. I did think a lot about how vital it is for me to empower her now, even at age 3. To encourage her to go out and grab whatever it is she wants in life, to lead. It starts with the constant, steady assurance that the top job is attainable.

Becoming a filmmaker is not easy. It's years of rejection and disappointment and it's very hard, often grueling work. The job takes insane levels of endurance and sometimes delusional amounts of self-confidence. All I can do is raise one girl with that kind of fearlessness, then let her choose her path. That's my contribution. The rest is up to her.

(Should I mention we need more female chefs? Different article.)