The Films Of Stanley Kubrick Ranked: Noir, War, And The Outer Reaches Of Existence

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

There isn't a thing that hasn't been written about the films of Stanley Kubrick. His films have been celebrated and reviled; some originally reviled have been reassessed as masterpieces; reams of copy have been written on even his least-appreciated movies. And yet they pull us in time and again. His films feature richly developed concepts that we can appreciate differently as our own lives progress and change.

Kubrick is the most visible representation of a sort of filmmaking that has largely vanished. He was likely the last director to enjoy total creative freedom with the backing of a major movie studio; his deal with Warner Bros. let him do what he wanted, on his own time. His 1999 passing happens to coincide with the transition into a fully digital filmmaking era and into a time when studio films are ever-more focused on sequels and familiar concepts.

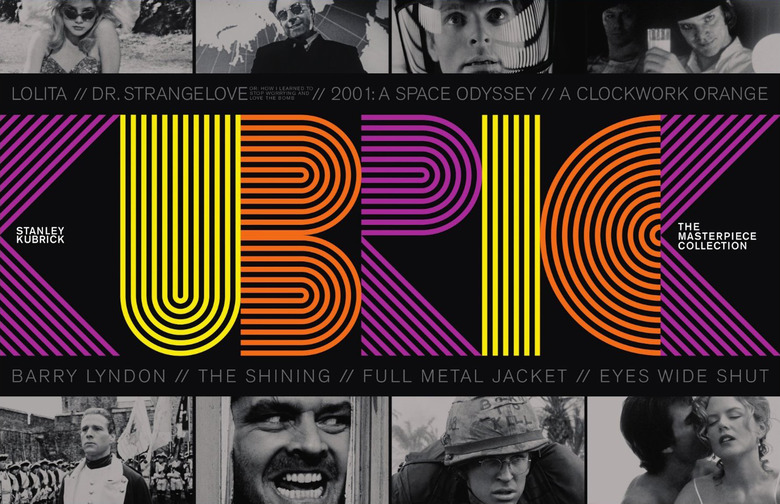

The idea of ranking Kubrick films is somewhat absurd; there's really only one that can be at #1. But there's a lot of room for discussion about what his other twelve features offer. Warner Bros. recently issued a new box set (Stanley Kubrick: The Masterpiece Collection) with a gorgeous outer shell (above), a fine array of behind the scenes material, and disc packaging that is an improvement over the last blu-ray set from the studio. That box of eight films had us going back through all of Kubrick's movies, and we've laid them out in order below.

13. Fear and Desire (1953)

13. Fear and Desire (1953)

Kubrick's very first feature is also his first war movie, telling the story of four soldiers and their experience behind enemy lines. It is a more abstract film than the war film he would make four years later, and is very evidently the work of an untested filmmaker. But it is also the product of willpower and shows Kubrick's exceptional eye for composition. Kubrick essentially disowned the film, considering it an overly amateur effort, and put some effort into preventing it from being seen in the years prior to his death.

Rewatch it For

The experience of seeing the film at all, which most audiences haven't enjoyed. Fear and Desire was relatively unavailable until only a few years ago, and a recent disc release put Kubrick's first feature squarely back into consideration as a major moment in his career.

12. Lolita (1962)

12. Lolita (1962)

A popular novel from one of the most significant authors of the 20th Century gave Kubrick controversial source material on which to spend credit earned with Spartacus, for a film that may be his one genuine misfire. So much of what we recognize as elements of Kubrick's style come into play as the documentary elements of his pre-Spartacus movies fall away in favor of a focus on meaty performances and material that challenges contemporary moral standards. Here, Kubrick's pushback against conventional ideas of what is permissible is weakened by his inexperience and the strength of the production code. The film's somewhat bland irony and darkly comic approach don't jibe with the characters, especially as Kubrick cut scenes from the novel showing Lolita's real reaction to the "romance" with Humbert. Lolita is now quite difficult to watch — in many ways it is Kubrick's first horror film.

Rewatch it For:

Peter Sellers' performance as Claire Quilty, the role that Kubrick greatly expanded from its relatively small presence in the novel into a pessimistic complement for Humbert Humbert.

11. Killer's Kiss (1955)

11. Killer's Kiss (1955)

The first of two '50s noir pictures from Kubrick, Killer's Kiss is a raw genre story about a boxer, a dancer, and her brutish employer. On the script side the film is rough, but Kubrick's early filmmaking style has already improved considerably since the creation of Fear and Desire two years prior. This might be more effective as a silent film, as the images are powerfully evocative, with an impressive use not only of light and shadow, but of space. Kubrick's work as a photographer informs the location shooting, which documents mid '50s New York through Kubrick's intelligent eye.

Rewatch it For

The boxing sequence in the middle of the film, which breaks from the rest of the film's naturalistic style to offer something a bit more impressionistic and immersive, and stands as an influence on Martin Scorsese's Raging Bull.

10. Spartacus (1960)

10. Spartacus (1960)

More important to the biographer than the viewer, Spartacus sees Kubrick employed as a director for hire thanks to the intervention of Kirk Douglas. As studio epics go this is still an impressive effort, and one has to admire the fact that the relatively young Kubrick stepped onto set with a cast of luminaries and took charge to create something a bit like a film he might have conceived. Still, it's not quite like a Kubrick movie, and even the most significant aspect of the film's production — that Dalton Trumbo was credited under his own name, breaking the Hollywood blacklist that had been established as part of a Communist witch hunt a decade earlier — was the result of efforts from Douglas, not Kubrick.

Rewatch it For

Some understanding of the fact that even the most powerful directors can be faced with compromise, and that the creation of great work in film is always a collaborative experiment.

9. The Killing (1956)

9. The Killing (1956)

Kubrick's third feature is the first working with a cinematographer, and in many ways this feels like a refinement of his prior feature, Killer's Kiss. The subject matter is different — here, Sterling Hayden leads a crew of men who seek to rob a race track — but the feeling is much the same. The film is personified by a narrator who keeps a reporter's distance from the story, but the separation between a cold narration and the increasingly violent events related to the robbery breaks down as we're pulled into the gang's inner workings. A sense of humor glimmers here and there, but Kubrick keeps things tamped down until the ending, in which fate is incarnated as an irascible, irritating little dog.

Rewatch it For

The playful use of non-linear storytelling, awkward as it may be, which is planned as meticulously as the robbery depicted in the film.

8. Full Metal Jacket (1987)

8. Full Metal Jacket (1987)

There's little place for subtlety in a war film, and this split-hemisphere film is bound and determined that we get it. From the halved structure to the dual characters of privates Joker and Pyle right down to Joker's conflicting peace sign and "Born to Kill" buttons, Full Metal Jacket is like a set of nesting dolls. Dig down deep to the center, to the image of what man can be at the core, and there's just a tiny little thing, recognizably related to the outer shells, but stripped of any nuance or embellishment. It is a simple, brutal film in many respects, and bravura performances from Matthew Modine and Vincent D'Onofrio give it an irresistible energy.

Rewatch it For:

The second half of the movie, too-easily dismissed in favor of the more conventionally accessible boot camp narrative, in which Joker's smug personality is tested as he finds exactly the thing he sought out of war.

7. A Clockwork Orange (1971)

7. A Clockwork Orange (1971)

Kubrick's adaptation of Anthony Burgess' novel is an eye-opening visual achievement, with a sonic accompaniment that is almost as eccentric as the film's costumes and environments. And while its depiction of youth gangs and the authoritarian methods considered to control crime is starkly reductionist, that works in the service of creating a horrific vision of a society that is bereft of ideas, and even totally inept in its attempt to achieve balance between the state and the impulses of an individual.

Rewatch it For

The wide-angle photography, which highlights the magnificent combination of locations and production design, but which also gives the film's violence an uncomfortably grounded basis in reality.

6. Paths of Glory (1957)

6. Paths of Glory (1957)

Kurbick's second war film is a searing anti-war document that contains some of the most devastating images of WWI put to film — both in scenes that take place on the battlefield, and in the courtroom where soldiers are tried for cowardice to cover failures at higher levels of command. There is even less hidden below the surface here than in Full Metal Jacket, as the script (a collaboration with crime author and The Killing co-writer Jim Thompson) is angrily didactic. But given the message at hand, it is impossible to consider that entirely a fault. Through technique that has grown in bounds since his debut, Kubrick keeps the proceedings tense and riveting.

Rewatch it For

The fusion of Kubrick's first-phase documentary influence combined with the period recreation of trenches and WWI battlefields, which creates images of man-made catastrophe that are unforgettable.

5. The Shining (1980)

5. The Shining (1980)

Horror is made of all the same stuff of drama, perhaps in different proportions. Kubrick cast aside much of Stephen King's fairly balanced conception for The Shining, particularly elements of plot and character, in order to focus on atmosphere. Through his impeccable craft and patient eye, the result of that effort is a horror film that is close to pure experience. The Shining feels bigger than the screen that holds it as the Overlook Hotel could almost stretch off the sides of the screen to actually envelop the audience. The effect of The Shining's specific patterns of sound and image is like bridging zones of abstract and concrete thinking to create an all encompassing feeling of inescapable dread that goes beyond the experience of this family trapped in a remote hell.

Rewatch it For:

The use of space, always a hallmark of Kubrick's work, but which here is a dominant characteristic, and a thing that is dramatically different from the style of horror that has evolved in the decades since this film was released.

4. Barry Lyndon (1975)

4. Barry Lyndon (1975)

Kubrick never got to make his Napoleon movie, but his adaptation of the William Makepeace Thackeray novel The Luck of Barry Lyndon, a rambling tale of a dopey Irish rogue, serves in its stead as an adventure movie slash chamber drama in which Kubrick could indulge a meticulously recreated 18th Century period aesthetic. This film is the Eyes Wide Shut of the '70s: a movie heralded by great anticipation that was received with disappointment on release, and relegated to an afterthought by those interested in only the most superficial aspects of Kubrick's filmmaking. And, like Eyes Wide Shut it offers ample rewards for patient viewers, as the story of Barry's rise in society — through events barely within his control — and his inevitable fall proves to be an observant character piece with ample opportunities for a giant cast to shine.

Rewatch it For:

The glorious light and the cinematography by John Alcott, which is the most beautiful work achieved by any of Kubrick's collaborators.

3. Eyes Wide Shut (1999)

3. Eyes Wide Shut (1999)

Fifteen years later, some still don't know what to make of Kubrick's final film, despite having ample time to reconcile their own desires for another 2001 or Full Metal Jacket with the fact that Kubrick spent his last years focusing on some of the most mundane and the most persistently troublesome aspects of our everyday existence. Eyes Wide Shut is a clear-eyed vision of stunted masculine sexuality and a particularly perceptive examination of the sexual power dynamics within a marriage. There's a specific irony to the fact that Kubrick, a man said to be cold and distant, ended his career with an un-anambigious invocation of sex as an all-encompassing communication between this troubled couple. (Given Kubrick's nature, I fully expect that was a deliberate action on his part.) Nicole Kidman's delivery of the final line — "F***." — may be one of the heaviest single-word statements in cinema.

Rewatch it For:

Tom Cruise, as this is among the most adroit uses of Cruise's particular screen personality. Cruise is a movie star who has been called the sexiest man alive (thanks, People Magazine!) but whose roles are often curiously chaste. Kubrick uses him as a guy who has no idea how to handle sexual impulses, and whose journey through a dreamlike night of escalating sexual situations challenges not only the character, but the very image of Cruise as sex object.

2. Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964)

2. Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964)

Comedy is the ultimate tool in fiction — a raw, brutal drama will challenge audiences and might turn away as many people as it attracts, but even the most savage comedy seems easier to swallow. Strangelove is an exceptionally savage comedy — and a wildly funny one — and a film in which Kubrick's skill as a director fully comes into focus. This is his first truly commanding work, with masterfully-pitched tone, an impeccable eye for detail, and and a satirical spirit that is every bit as trenchant now as it was fifty years ago. There's no single moment in comedy that sums up the totally blinkered insanity of politics like the delivery of "Gentlemen you can't fight in here, this is the war room!"

Rewatch it For:

The minor key comic perfection of Sterling Hayden, whose performance not only stands up against Peter Seller's exuberant grandstanding and George C. Scott's bigger-than-big delivery, but creates a portrait of a scarily whacko authority figure which is unsettlingly believable.

1. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

1. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

There's a point at which we have to set aside personal preference and subjective experience to understand pure achievement, and there isn't much pure achievement in cinema to rival 2001. Developing the story with Arthur C. Clarke, Kubrick reached to the furthest reaches of potential human experience, and together they are able to take any willing audience to both the beginning and end of humanity as we understand it. Kubrick's film and Clarke's novel are perfect paired companions, but on its own 2001 is a unique achievement, a piece of cinema that encompasses every aspect of filmmaking known at the time, from the utterly mundane to the experimental and the technologically advanced. The visual conception of that journey is dazzling; the compression of nearly all of human history and achievement into a single cut is sublime; the vision of a potential expanded consciousness is extraordinary.

Rewatch it For

The deep perspective on our own place in the universe. Kubrick and Clarke take blankly objective stock of where we come from while also remaining optimistic that there are evolutionary paths yet to explore.