'Cutie And The Boxer' Review: Perceptive Documentary Examines Sacrifice, Love, And Art [Sundance 2013]

First-time feature documentary director Zachary Heinzerling makes a quietly assured debut with the tender and perceptive Cutie and the Boxer. In documenting the 40-year marriage between Japanese "action painter" Ushio Shinohara and his wife Noriko Shinohara, the film paints a keen vision of the ways in which the halves of a life-long couple learns to life with, and often in spite of one another.

At 41, Ushio was an established Neo-Dadaist painter and sculptor in Japan who had emigrated to the US in an attempt to bring his work to a larger stage. Struggling with visibility, he met Noriko, a 19-year old student. The two quickly married and conceived a child. Before long their relationship hit a point where Noriko acted as assistant, cook, and cheerleader to Ushio, and found her own artistic ambitions thwarted. Over four decades their life has remained nearly in stasis, with classic gender roles defining and confining both individuals.

Cutie and the Boxer finds the couple on shaky financial ground, with Ushio making a last grasp at defining his importance, and Noriko finding herself more and more ready to break out an artistic identity of her own. She creates quirky and endearing comic strip tableaux, inspired by her past, in which characters Cutie and Bullie stand in for the real-life couple. Heinzerling animates some of her work to explain the duo's history, and conducts intimate interviews with the couple to get at the heart of their unusual relationship.

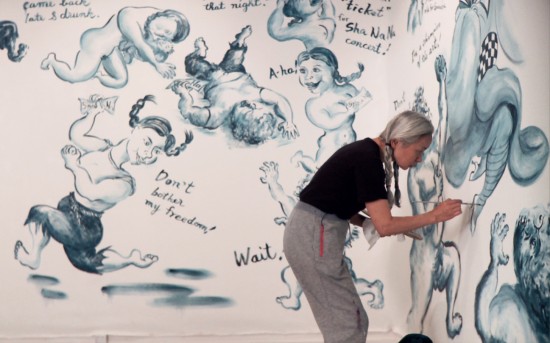

It's not for nothing that Ushio's alter-ego is "Bullie." His past as a boxer informs much of his life — the man's most notable work is his "action painting" concept. That's when the painter straps on boxing gloves fitted with paint-soaked sponges, and then punches a canvas for a minute or two. He's aggressive with Noriko, too, saying she should be there to "support the genius." Prior to sobriety, his alcoholism provided another justification for expressions of anger.

Trouble is, despite the action paintings being fairly cool, Ushio's latest work isn't always that great, and his eccentric sculptures aren't easily salable. To my eye, at least, Noriko's art is more directly communicative, and more meaningful. He's lashing out, or at best trying to reflect the energy and nature of his surroundings. She's doing the same to a certain extent, but in a far more controlled manner, and her "surroundings" are really Ushio. His expression is a bellow; hers is far more nuanced. No wonder, then, that when they finally do a collaborative show, it's called "Love is a ROARRR."

So why does she stay? There isn't one easy answer, though Heinzerling's very intimate interviews provide some illumination. The pair have a son, the alcoholic artist Alex, whose talent probably eclipses that of his father. But so too does his reliance on booze. He glues the two together, as does some sense of duty. More than anything else, Noriko seems to derive some momentum from the relationship, and certainly an artistic inspiration. The idea of "taming Bullie" crops up often in her work. She tells Ushio directly ""I feel so free when you're not around," but she displays a sense of place and control with him.

Cutie and the Boxer respects the close proximity the Shinoharas grant Heinzerling. The director's camera — which captures images that are unflattering but paradoxically beautiful — probes without jabbing, and cuts through decades of history to lay bare simple inequities in the couple's life. It's a gorgeous film, and though occasionally uncomfortable, Heinzerling doesn't provoke or revel in awkward revelations.

It's frequently surmised that the presence of a camera can cause changes in a documentary subject. Here, it's fair to wonder if the camera was catalyst for a new phase of self-awareness in Ushio. As one of the artists says while poking around piles of art in his studio, "it's hard to say what is good, bad, finished, or unfinished." I suspect Cutie and the Boxer provides some valuable clarity.

/Film score: 8.5 out of 10

(Cutie and the Boxer won the Directing Award in the US Documentary category at Sundance this year. RADiUS-TWC, a division of The Weinstein Company, picked it up for US distribution at the fest.)

A few footnotes:

A few footnotes:

First, a word about the music, which is contributed by the Japanese saxophonist Yasuaki Shimizu. As a player, Shimizu is famous for his sax arrangements of Bach, some of which appear in the film. His original compositions for the film a reminiscent of a variety of work: a bit of Ethiopian jazz, a bit of Vince Guaraldi, and a dose of downtown NYC jazz. The score provides a lovely extra dimension to the film.

Here's a sample of Shimizu's approach to arranging Bach:

Here's footage of Shinohara's 'action painting,' as performed at Sundance this year to promote the film:

This 'meet the filmmaker' piece on Heinzerling shows a bit of the film, and gives a taste of the score: