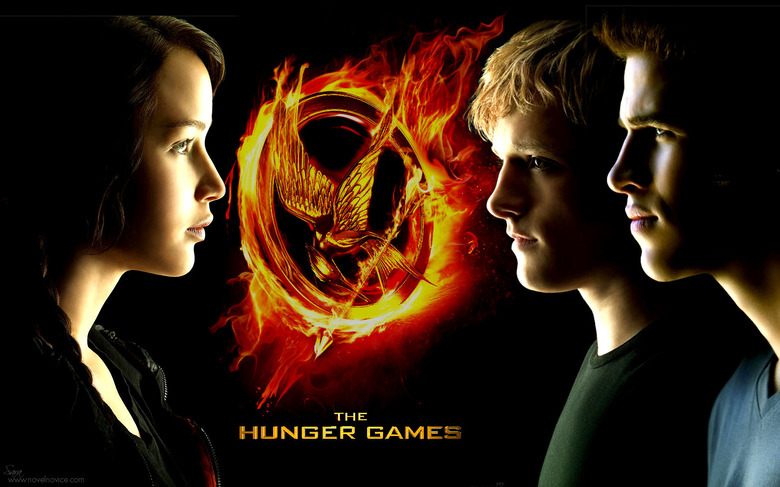

'The Hunger Games' Review: Jennifer Lawrence Commands A Lightweight Dystopian Vision

There's a great semi-futuristic story of brutal combat, in which a battered nation is captivated as two-person teams battle one another to the death in an ironic but potent allegory of public entertainment and government control gone wrong. A reserved but driven hero manipulates public perception to gain an edge in the games, and could ultimately become something more significant than a survivor.

I'm not thinking of The Hunger Games; I'm thinking of Paul Bartel's Death Race 2000, released in 1975 and made under producer Roger Corman. Death Race 2000 does a lot of things right, as Corman's shoestring affairs go. It has the silly, exploitative and satirical angles covered with material to spare. What it doesn't have, however, is a truly compelling main character. The Hunger Games has that one thing Bartel didn't: a killer lead performance, in this case from Jennifer Lawrence as the young family provider turned warrior Katniss Everdeen. That's just about all it's got.

As satire and allegory, The Hunger Games is a whiff and a miss. But as a portrait of Katniss, it has the benefit of featuring Lawrence in nearly every scene, and the young actress doesn't squander the movie's opportunity. I suspect that in twenty years Winter's Bone will be the movie in which we turn back to see Lawrence play an impressive provider, but The Hunger Games makes a good introduction to the fierce Lawrence, if nothing else.

Director Gary Ross and screenwriter Billy Ray worked with author Suzanne Collins to script a film based on the first novel in her trilogy of stories set in Panem, a sort of future United States in which states have been replaced by twelve Districts. As punishment for a past rebellion — we don't know how far in the past, but it has been a good while — once a year each District is obligated to submit two young citizens to The Hunger Games, a contest in which the twenty-four kids fight to the death, leaving a single winner.

What does that winner get, besides their life? The film isn't very specific. I haven't read Collins' novel, but seeing that the districts are portrayed as quite poor while their Capitol is wealthy to the point of shameless fashion and decadence, it seems likely that food or economic favor is a reward. Food and welfare is a definite concern of Katniss who, along with her District 12 acquaintance Peeta Mellark (Josh Hutcherson) ends up representing her home in the Games. Katniss has family in mind, too, as she volunteers for the games to keep her younger sister from going, and likely dying. She leaves behind a possible love interest, Gale (Liam Hemsworth), who plays a minor role, at best.

Collins, Ray and Ross work hard in an attempt to build a world, and Panem is built on a bedrock of very loaded narrative allusions: the American Civil War; the dustbowl documentary work of Walker and Evans; the overdone fashions and empathetically-drained tendencies of reality TV. The wealthy populace of the Capitol embodies major concepts from both Orwell and Huxley. Yet none of those allusions become a framework for deeper concern about what plagues Panem, and how it might reflect anything about us. The Hunger Games isn't about anything but Katniss and her will to survive.

And so tip your hat to Gary Ross his associates for casting Jennifer Lawrence, who is able to carry much of the film simply on that drive. As she goes from District to Capitol to the fields of the Games, where hidden controllers can dial up threats on a whim, Lawrence is centered, but urgent. When Ross and the script leave pretty big gaps with respect to her potential love affair with Peeta, and what that means for the Games, Lawrence is able to give us all we need to know.

I wasn't as taken with Josh Hutcherson's performance; I suspect Peeta is a weaker character on screen than he was on the page. While Hutcherson is always fine, he's marginalized a bit by the film. He isn't helped by the fact that the most propulsive first half of the Games gives him less to do; he's much more prominent in the second half of the combat, when the action starts to drag.

Lenny Kravitz works well as the stylist who helps Katniss earn a legion of fans, while Stanley Tucci mugs relentlessly as the Capitol's chief TV personality. (More than a few shades there of the Real Don Steele from Death Race 2000.) Elizabeth Banks is fine as Effie Trinket, another Capitol citizen working with the District 12 kids. But I don't think she's ever actually named in the film, and she's one of many characters that are realized more as fan service than as legitimate entities.

Lawrence is almost good enough to convince me that the ruling class of Panem is powerful and vindictive and willing to punish those who don't conform to the Games. She seems afraid, at least. But when you get down to it, the aggressiveness of the State seems like a giant put-on. Sure, we see a minor rebellion being squashed in one District, but I saw more horrifying police action in videos from Occupy Wall Street protest marches. Twenty-three kids are killed every year in the Games? That's a terrible loss, but as a tool to control an entire country, it feels like something is missing. The citizens of Panem are cowed, but the film does a poor job communicating why, much less how. As a dystopian vision The Hunger Games makes fierce faces, but it doesn't have any fangs.

That toothlessness left me caring only about Katniss, but thanks in part to the very evident franchise-building construction, the conclusion of The Hunger Games feels like a fait accompli almost from the first act. The film's final confrontation is a total anti-climax, and I realized I don't care about what happens next. With two more films to go in this series The Hunger Games aims neither for a triumphant victory or a dour cliffhanger. Instead it shoots down the middle, and the conclusion hits with all the power of a shrug. In theory, we might eventually be able to look back on a full film trilogy and see a compelling allegory of the survival of both individuals and society despite a heavy-handed State. But as a standalone film, The Hunger Games is a protracted single-act play with a hell of a lead performance.

/Film score: 5.5 out of 10