Tales From Development Hell: Darren Aronofsky's 'Batman: Year One' Starring Clint Eastwood

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

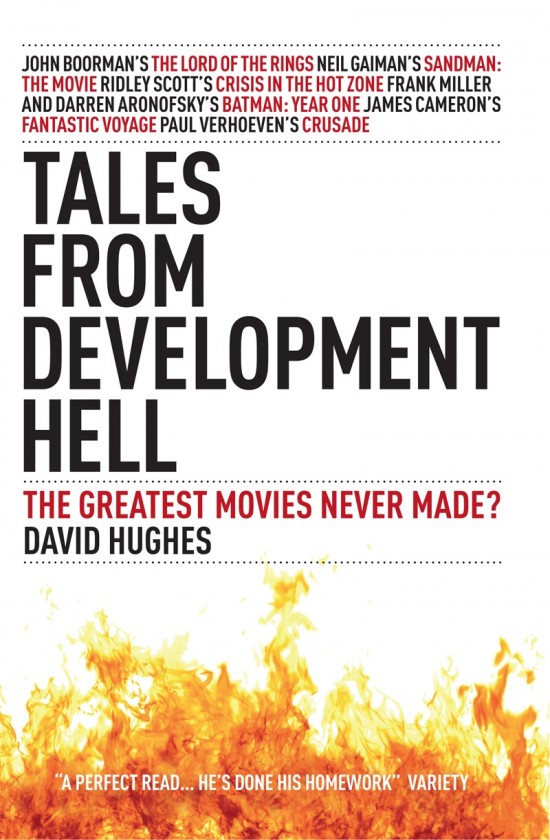

Titan Books has provided /Film with an exclusive excerpt from David Hughes' upcoming book Tales From Development Hell: The Greatest Movies Never Made? I've had a preview copy of the new updated edition and have been enjoying it thoroughly. There is some truly great and frustrating stories within — including the big screen adaptation of Neil Gaiman's Sandman, Ridley Scott's Crisis in the Hot Zone which collapsed days before filming, James Cameron's Fantastic Voyage, the long road to bring The Lord of the Rings to the big screen (one incarnation featured the Beatles), the many scripts and long development of Indiana Jones 4, and many others.

Probably the best chapter in the book focuses on the history of Batman adaptations, including Darren Aronofsky and Frank Miller's adaptation of Batman: Year One starring Clint Eastwood. After the jump you will find an excerpt of this chapter.

Few heroes have inspired so many stories as the costumed crime fighter known to almost every man, woman and child on Earth as Batman. The creation of cartoonist Bob Kane and his (mostly uncredited) partner Bill Finger, Batman made his first appearance in Detective Comics #27, published in May 1939 — a year after Superman's début. Lacking the superpowers of his predecessor, 'The Bat-Man' was forced to rely on his physical prowess, and the enormous wealth of his alter ego, the millionaire playboy Bruce Wayne, who provided his costumed counterpart with a house (the Batcave), a car (the Batmobile), an aircraft (the Batplane) and a utility belt full of gadgets. Kane credited numerous influences for his creation, including Zorro, The Shadow and a 1930 film entitled The Bat Whispers, which featured a caped criminal who shines his bat insignia on the wall just prior to killing his victims. "I remember when I was twelve or thirteen... I came across a book about Leonardo da Vinci," Kane added. "This had a picture of a flying machine with huge bat wings... It looked like a bat man to me."

Batman first reached the silver screen as early as the 1940s, with the first of two fifteen-chapter Columbia serials: Batman (1943), starring Lewis Wilson as the Caped Crusader, and Batman and Robin (1949), with Robert Lowery. Almost two decades later, on 12 January 1966, the ABC television series starring Adam West and Burt Ward brought the characters to an entirely new generation, running for only two seasons, but earning a quickie big-screen spin-off within the first year. Although Kane's earliest stories had a noir-ish sensibility, over time the characters developed the more playful personae that were magnificently captured by the camp capers of the TV series. "Batman and Robin were always punning and wisecracking and so were the villains," Kane said in 1965. "It was camp way ahead of its time." In the 1970s, Batman continued to appear in an animated series, Superfriends, but the legacy of the 1960s TV series meant that it was not until Frank Miller reinvented the character for the darkly gothic comic strip series The Dark Knight Returns and Batman: Year One in the mid-1980s that the world was ready to take Batman seriously again.

Just as Batman had made his first appearance in comic strips a year after Superman, the development of the Batman movie — the first since the 1966 caper with Adam West — began a year after the blockbuster success of Superman: The Movie in 1978. Former Batman comic book writer Michael E. Uslan, together with his producing partner Benjamin Melniker, secured the film rights from DC Comics, announcing a 1981 release for the film, then budgeted at $15 million. Uslan and Melniker hired Superman's (uncredited) screenwriter Tom Mankiewicz to script the story, which was set in the near future, and closely followed the Superman model: an extended origin story, followed by the genesis of his superhero alter ego, and his eventual confrontation with The Joker. It ended with the introduction of Robin. It was Uslan's wish to make "a definitive Batman movie totally removed from the TV show, totally removed from camp; a version that went back to the original Bob Kane/Bill Finger strips."

By 1983, the project was still languishing in Development Hell, as potential directors including Ivan Reitman (Ghostbusters) and Joe Dante (Gremlins) came and went. It was following the surprise success of Tim Burton's slapstick comedy Pee-Wee's Big Adventure that Warner Bros — whose stewardship of the project resulted from a deal with Peter Guber's Casablanca Film Works, with whom Melniker had a development deal — offered the project to lifelong Bat-fan Tim Burton, who was busy making Beetlejuice for the studio. "The first treatment of Batman, the Mankiewicz script, was basically Superman, only the names had been changed," Burton told Mark Salisbury. "It had the same jokey tone, as the story followed Bruce Wayne from childhood through to his beginnings as a crime fighter. They didn't acknowledge any of the freakish nature of it... The Mankiewicz script made it more obvious to me that you couldn't treat Batman like Superman, or treat it like the TV series, because it's a guy dressing up as a bat and no matter what anyone says, that's weird." Although Burton had fond memories of the series, which he would run home from school to watch, he had no wish to duplicate its campy tone. Yet it would take the comic book boom of the late 1980s — notably the success of the collected edition of The Dark Knight Returns — to convince Warner Bros that Burton's approach might connect with audiences. "The success of the graphic novel made our ideas far more acceptable," he observed.

With Warner Bros' blessing, Burton began working on a new draft with emerging screenwriting talent and fellow Bat-fan Sam Hamm, whose comedy script Pulitzer Prize had sparked a bidding war and landed him a two-year contract with Warner Bros. Hamm felt that the Superman model was wrong; that rather than dwell on Batman's origins, the character should be presented as a fait accompli, with his background and motivations emerging as the story progressed, so that the unlocking of the mystery becomes part of the plot. "I tried to take the premise which had this emotionally scarred millionaire whose way of dealing with his traumas was by putting on the suit," Hamm said. "If you look at it from this aspect, that there is no world of superheroes, no DC Universe and no real genre conventions to fall back on, you can start taking the character seriously. You can ask, 'What if this guy actually does exist?' And in turn, it'll generate a lot of plot for you." Burton liked the approach: "I'd just meet Sam on weekends to discuss the early writing stages. We knocked it into good shape while I directed Beetlejuice, but as a 'go' project it was only green-lighted by Warners when the opening figures for Beetlejuice surprised everybody — including myself!"

Mel Gibson, Alec Baldwin, Bill Murray, Charlie Sheen and Pierce Brosnan were all rumoured to be on Warner Bros' shortlist for the title role, although Jack Nicholson's casting as The Joker meant that the studio could afford to go with an unknown — after all, it had worked with Christopher Reeve for Superman. Burton had his doubts. "In my mind I kept reading reviews that said, 'Jack's terrific, but the unknown as Batman is nothing special,'" he told Mark Salisbury. Neither did he want to cast an obvious action hero — "Why would this big, macho, Arnold Schwarzenegger-type person dress up as a bat for God's sake?" Finally, it came down to only one choice: Michael Keaton, whom he had just directed in Beetlejuice. "That guy you could see putting on a bat-suit; he does it because he needs to, because he's not this gigantic, strapping macho man. It's all about transformation..." observed Burton. "Taking Michael and making him Batman just underscored the whole split personality thing which is really what I think the movie's all about."

By this time, Hamm's involvement had been sidelined by the writers' strike, so Burton brought in Beetlejuice writer Warren Skaaren and Charles McKeown (The Adventures of Baron Munchausen). Their principal job was to lighten the tone — not because of Keaton's casting, but because of studio fears that a troubled and disturbed Batman, full of self-doubt and unresolved psychological issues, might turn off audiences. "I see what they're doing," Hamm conceded, "in that they don't want to have a larger-than-life, heroic character who is plagued by doubts about the validity of what he's doing, but it's stuff that I miss."

Principal photography began under tight security in October 1988. Although Sean Young's riding accident threw the schedule out at an early stage, it could have spelled disaster for the production had it occurred later in the shoot; as it was, none of her scenes had to be re-shot when Kim Basinger stepped into Vicki Vale's shoes. In spite of this early setback, the sheer scale of the production, the complexity of the special effects, the extensive night shoots, the large number of interior and exterior locations, and the restrictive nature of Jack Nicholson's contract — which, despite his enormous fee, meant that he could only be called for a specified number of hours per day, including time spent in the makeup chair — Burton delivered the film on schedule, and only a fraction over budget. The anticipation for Batman was running at fever pitch by the time the film finally hit US cinemas on 21 June 1989, swooping to a record-breaking $42.7 million opening weekend, becoming the first film to hit $100 million after just ten days on release, and grossing $413 million worldwide. 'Bat-mania' swept the planet, with the film becoming not only the biggest film of 1989, but perhaps more significantly the most successful in Warner Bros' history. Thus, it came as no surprise when the studio invited Burton back up to bat for the sequel. No one was more surprised than the director, however, when he said yes.

Although Warner Bros left the Gotham City set standing at Pinewood Studios (at a cost of $20,000 per day) in the hopes that the success of Batman would warrant a sequel, Batman Returns was ultimately shot in Los Angeles, with Burton again at the helm, and Michael Keaton back in the Batsuit. This time, Burton's dark sensibilities were given a freer reign, with The Penguin (Danny DeVito) and Catwoman (Michelle Pfeiffer) as the villains. Sam Hamm's script (which also featured Catwoman) was rejected in favour of one by Heathers scribe Daniel Waters, which was subsequently doctored by Wesley Strick (Cape Fear).

"When I was hired to write Batman Returns ([called] Batman II at the time), I was asked to focus on one (big) problem with the current script: Penguin's lack of a 'master plan'," Strick recalls. "To be honest, this didn't especially bother me; in fact I found it refreshing — in comic book stories, there's nothing hoarier or (usually) hokier than an arch-villain's 'master plan'. But the lack of one in Batman II was obsessing the Warner brass." Strick says that he was presented with "the usual boring ideas to do with warming the city, or freezing the city, that kind of stuff." (Warner executives evidently continued to have similar ideas as the years passed: a frozen Gotham ended up as a key plot device in Batman & Robin.)

Strick pitched an alternative approach — inspired by the 'Moses' parallels of Water's prologue, in which Baby Penguin is bundled in a basket and thrown in the river where he floats, helpless, till he's saved (and subsequently raised) by Gotham's sewer denizens — in which Penguin's 'master plan' is to kill the firstborn sons of Gotham City. Warner Bros loved it, and so did Burton. However, as Strick admits, "It turned out to be a controversial addition. The toy manufacturers were not alone in disliking it — it also did substantially less business than the first [Batman]." Indeed, although Batman Returns scored a bigger opening weekend ($45.6 million) than its predecessor, its worldwide gross was $282.8 million, barely two thirds of Batman's score.

Joel Schumacher's Batman Forever (1995) — featuring Val Kilmer as Batman, Jim Carrey as The Riddler, Nicole Kidman as love interest Dr Chase Meridian, Chris O'Donnell as Robin, and (despite the casting of Billy Dee Williams as Harvey Dent in Batman) Tommy Lee Jones as Harvey Dent/Two-Face — bounced back, with a $52.7 million opening weekend and a worldwide gross of $333 million. Yet the $42.87 million opening weekend and mere $237 million worldwide gross of the same director's Batman & Robin (1997) — with George Clooney and Chris O'Donnell as the titular dynamic duo, Arnold Schwarzenegger as Mr Freeze, Uma Thurman as Poison Ivy and Alicia Silverstone as Batgirl — effectively put the franchise on hiatus, despite a reported $125 million in additional revenue from tie-in toys, merchandise, clothing and ancillary items.

Despite the fact that, as far as Warner Bros was concerned, the future of the franchise remained in doubt, a plethora of rumours, lies and/or wishful thinking circulated about a fifth Batman film. Madonna had been cast as The Joker's twisted love interest, Harley Quinn. The adversary in Batman 5 was to be The Sacrecrow — a second rank villain first introduced in the comics in 1940 — played by John Travolta, Howard Stern or Jeff Goldblum (depending on which source you believed). Jack Nicholson was returning as The Joker, possibly in flashback or as hallucinations invoked by The Scarecrow. "The Joker is coming, and it's no laughing matter," Nicholson himself reportedly teased journalists when asked about upcoming projects at a press conference for As Good As It Gets. In fact such was the level of scuttlebutt in the months following the release of Batman & Robin that several of the most prominent Internet rumour-mills — including Dark Horizons and Coming Attractions — took the unusual step of placing a moratorium on Batman 5 rumours. Yet from all this sound and fury a few tales of the Bat did emerge which appeared to have an element of truth. One was that Mark Protosevich — who scripted The Cell and Ridley Scott's unproduced adaptation of I Am Legend for Warner Bros — had written a script, entitled either Batman Triumphant or DarkKnight, which featured Arkham Asylum, The Scarecrow and Harley Quinn, as well as numerous nightmarish hallucinations of Batman's past.

One of the biggest rumours centred on the casting of Batman himself. Despite the fact that George Clooney was contracted to make at least one more film in the series, Kurt Russell — then starring for Warner Bros in Paul Anderson's ill-fated Soldier — was widely reported to be in line for the role, although producer Jon Peters was dismissive. "He's not Batman," he told Cinescape. "Forget it. How could he be Batman? He's my age. He could be Batman's father, but not Batman." The studio, apparently hoping to break the 'revolving door' casting of the Batman role, publicly stood by Clooney, who appeared willing to fulfil his contract. "If there is another, I'd do it," he told E! News in September 1997. "I have a contract to do it. It'd be interesting to get another crack at it to make it different or better. I'll take a look at [Batman & Robin] again in a couple of months," he added. "I got the sense that it fell short, so I need to go back and look at it, see what I could have done better."

Although Clooney believed he had "killed the franchise", it was director Joel Schumacher, who had wrenched the series almost all the way back to the campy style of the sixties TV show, who bore the brunt of the blame for the relatively poor performance of Batman & Robin. "I felt I had disappointed a lot of older fans by being too conscious of the family aspect," he told Variety in early 1998. "I'd gotten tens of thousands of letters from parents asking for a film their children could go to. Now, I owe the hardcore fans the Batman movie they would love me to give them." The implication was that he would be asked to make another Batman, and on 1 July 1998 he went further, telling E! Online that he had talked with Warner Bros production chief Lorenzo di Bonaventura about the possibility of doing another one. "I would only do it on a much smaller scale, with less villains and truer in nature to the comic books," he said.

Schumacher's chief inspiration was Frank Miller's Batman: Year One, illustrated by Miller's Daredevil: Born Again collaborator David Mazzucchelli, using a heavily-inked, high-contrast style which recalled newspaper strips like Dick Tracy, and coloured with earthy tones by Richmond Lewis. In just four twenty-four-page issues, Miller rewrote the first year of Batman mythology from the point of view of James Gordon, a young police lieutenant still years away from his promotion to the more familiar rank of Commissioner. As Miller wrote in his introduction to the collected edition, "If your only memory of Batman is that of Adam West and Burt Ward exchanging camped-out quips while clobbering slumming guest stars Vincent Price and Cesar Romero, I hope this book will come as a surprise."

Year One begins as Gordon arrives in Gotham with his pregnant wife Ann, just as Bruce Wayne returns to the city where his parents were shot dead before his eyes eighteen years earlier. After twelve years of self-imposed exile, Wayne begins training himself for the double life he is soon to lead: layabout playboy by day, masked vigilante by night. However, while Bruce is discovering the difficulties inherent in trying to clean up streets that want to stay dirty, Lieutenant Gordon is finding that the corruption he encounters among street cops is endemic, and goes all the way to the top. Although Gordon initially endangers himself by exercising zero tolerance towards his corrupt colleagues, he also earns a reputation for heroics, making him as untouchable as he is incorruptible — until he slips into an affair with a beautiful colleague, Detective Essen, forcing him to admit his infidelity rather than give in to blackmail.

Meanwhile, just as a freak encounter with a bat has inspired Bruce Wayne to adopt an alter ego to strike fear into the dark hearts of the Gotham underworld — not to mention the same corrupt cops Gordon is fighting from the inside — so the 'Batman' inspires a cat-loving prostitute named Selina to switch careers, leaving the 'cathouse' (brothel) to become a costumed cat burglar. Finally, Batman narrowly escapes after being cornered in a tenement building and fire-bombed by Gordon's superiors — just in time to save Gordon's newborn baby from thugs, and thereby create an unofficial alliance between the two idealistic crime fighters, one in plain clothes, one in costume.

Despite Schumacher's interest in using Year One as the basis for a darker, grittier adaptation, in the summer of 1999 Warner Bros asked New York film-maker Darren Aronofsky, fresh from his breakthrough feature, Pi, how he might approach the Batman franchise. "I told them I'd cast Clint Eastwood as the Dark Knight, and shoot it in Tokyo, doubling for Gotham City," he says, only half-joking. "That got their attention." Whether inspired or undeterred, the studio was brave enough to open a dialogue with the avowed Bat-fan, who became interested in the idea of an adaptation of Year One.

"The Batman franchise had just gone more and more back towards the TV show, so it became tongue-in-cheek, a grand farce, camp," says Aronofsky. "I pitched the complete opposite, which was totally bring-it-back-to-the-streets raw, trying to set it in a kind of real reality — no stages, no sets, shooting it all in inner cities across America, creating a very real feeling. My pitch was Death Wish or The French Connection meets Batman. In Year One, Gordon was kind of like Serpico, and Batman was kind of like Travis Bickle," he adds, referring to police corruption whistle-blower Frank Serpico, played by Al Pacino in the eponymous 1973 film, and Robert De Niro's vigilante in Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver. Aronofsky had already noted how Frank Miller's acclaimed Sin City series had influenced his first film, Pi; in addition, the director already had a good working relationship with the writer/artist, since they had collaborated on an unproduced feature adaptation of Miller's earlier graphic novel, Ronin. "Our take was to infuse the [Batman] movie franchise with a dose of reality," Aronofsky says. "We tried to ask that eternal question: 'What does it take for a real man to put on tights and fight crime?'"

The studio was intrigued enough to commission a screenplay, in which Aronofsky and Miller took a great many liberties, not only with the Year One comic book, but with Batman mythology in general. For a start, the script strips Bruce Wayne of his status as heir apparent to the Wayne Industries billions, proposing instead that the young Bruce is found in the street after his parents' murder, and taken in by 'Big Al', who runs an auto repair shop with his son, 'Little Al'. Driven by a desire for vengeance towards a manifest destiny of which he is only dimly aware, young Bruce (of deliberately indeterminate age) toils day and night in the shop, watching the comings and goings of hookers, johns, pimps and corrupt cops at a sleazy East End cathouse across the street, while chain-smoking detective James Gordon struggles with the corruption he finds endemic among Gotham City police officers of all ranks.

Bruce's first act as a vigilante is to confront a dirty cop named Campbell as he accosts 'Mistress Selina' in the cathouse, but Campbell ends up dead and Bruce narrowly escapes being blamed. Realising that he needs to operate with more methodology, he initially dons a cape and hockey mask — deliberately suggestive of the costume of Jason Voorhees in the Friday the 13th films. However, Bruce soon evolves a more stylised 'costume' with both form and function, acquires a variety of makeshift gadgets and weapons, and re-configures a black Lincoln Continental into a makeshift 'Bat-mobile' — complete with blacked-out windows, night vision driving goggles, armoured bumpers and a super-charged school bus engine. In his new guise as 'The Bat-Man', Bruce Wayne wages war on criminals from street level to the highest echelons, working his way up the food chain to Police Commissioner Loeb and Mayor Noone, even as the executors of the Wayne estate search for their missing heir. In the end, Bruce accepts his dual destiny as heir to the Wayne fortune and the city's saviour, and Gordon comes to accept that, while he may not agree with The Bat-Man's methods, he cannot argue with his results. "In the comic book, the reinvention of Gordon was inspired," says Aronofsky, "because for the first time he wasn't a wimp, he was a bad-ass guy. Gordon's opening scene for us was [him] sitting on a toilet with the gun barrel in his mouth and six bullets in his hand, thinking about blowing his head off — and that to me is the character."

The comic and the script have many scenes in common — including Bruce Wayne's nihilistic narration (part Travis Bickle from Taxi Driver, part Rorschach from that other great late 80s graphic novel, Watchmen), a heroic Gordon saving a baby during a hostage crisis, Selina as proto-Catwoman, the beating Gordon receives from fellow cops as a warning to give up his war on corruption, his suspicion that Harvey Dent is The Bat-Man, and the climactic battle in the tenement building. But it acts as a jumping-off point for a much grander narrative. Although the script removes the subplot of Gordon's adultery, it goes further towards blurring the boundaries between accepted notions of good and evil: Gordon decries The Bat-Man's vigilantism as the work of a terrorist whose actions put him outside the law, not above it, unaware that it was as much his own televised declaration of war on crime and corruption which inspired Bruce to vigilantism as the senseless and random murder of Bruce's parents.

The script contains numerous references for Bat-fans, including a brief scene with a giggling green-haired inmate of Arkham Asylum, and goes a long way towards setting up a sequel, as Selina/Catwoman discovers the true identity of The Bat-Man. Interestingly, neither the comic book nor the script provide an entirely convincing argument for Bruce Wayne's transformation into Batman: while Year One takes a more traditional approach — a bat smashes through the window of Bruce's study — the script has Bruce take inspiration from the Bat-shaped mark produced by his signet ring (shades of Lee Falk's superhero The Phantom) which leads the tabloids to dub him 'The Bat-Man'.

In a rare interview, Miller told The Onion about working with Aronofsky. "He's a ball," he said. "Ideas just pour out of his ears. We tend to have a lot of fun together. It's funny, because in many ways I think I'm the lighter one of the team, and I'm not used to that." Although he would not talk about the content of the film "because I think Warner Brothers would have somebody beat me up," he observed that asking a screenwriter what the movie would be like "is like asking a doorman whether a building is going to be condemned." Nevertheless, Aronofsky believes that his and Miller's approach would have made Tim Burton's Batman look like a cartoon. "I think Tim did it very well," he says, "especially on his second film, which I think is the masterpiece of the series. But it's not reality. It's totally Tim Burton's world; a brilliant, well-polished Gothic perfection concoction. The first one did have a certain amount of reality, but there were still over-the-top fight sequences, and I wanted to have real fights, [explore] what happens when two men actually fight, which you just don't see. Because once you start romanticising it and fantasising it into super-heroics, in the sense of good guys versus bad guys, and you're not playing with the ambiguity of what is good and what is bad... I just could not find a way in for myself to tell that story.

Of his own approach, Aronofsky admits, "I think Warners always knew it would never be something they could make. I think rightfully so, because four year-olds buy Batman stuff, so if you release a film like that, every four year-old's going to be screaming at their mother to take them to see it, so they really need a PG property. But there was a hope at one point that, in the same way that DC Comics puts out different types of Batman titles for different ages, there might be a way of doing [the movies] at different levels. So I was pitching to make an R-rated adult fan-based Batman — a hardcore version that we'd do for not that much money. You wouldn't get any breaks from anyone because it's Warner Bros and it's Batman, but you could do it for a smart price, raw and edgy, and make it more for fans and adults. Maybe shoot it on Super-16 [mm film format], and maybe release it after you release the PG one, and say 'That's for kids, and this one's for adults.'" Nevertheless, he adds, "Warner Bros was very brave in allowing us to develop it, and Frank and I were both really happy with the script."

© 2012 by David Hughes. All rights reserved.

Order Tales From Development Hell: The Greatest Movies Never Made? now!