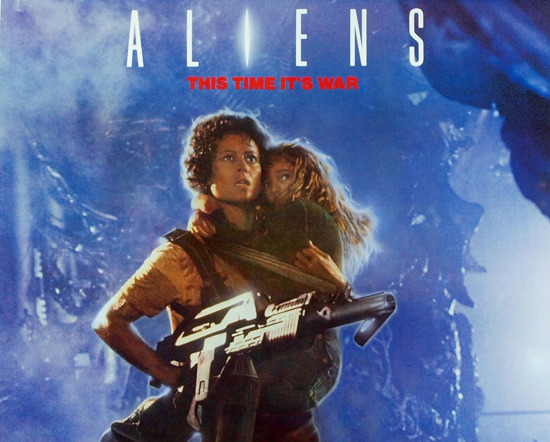

'Aliens,' James Cameron's Explosive Ode To Motherhood, Was Released Twenty-Five Years Ago Today

Twenty-five years ago, it was time for war. On July 18, 1986 James Cameron's film Aliens exploded into theaters and immediately became one of the few examples of a standout sequel in movie history. Picking up where Ridley Scott's Alien left off — with Sigourney Weaver as Ellen Ripley drifting asleep in the sci-fi version of a lifeboat — Aliens emulated its predecessor with character-centric thrills and expanded upon it by visualizing the killer aliens as a bee-like hive society.

The movie celebrates industrial and military design, as in the marine ship Sulacco, which lances through space like an ingenious fusion of rifle and projectile, or the smart guns which transform cinematic equipment (the Steadicam) into weapons. At the same time, it mocks big business (see Paul Reiser's sleazy company man Carter Burke) and presumptuous military might.

In a popular film culture dominated by buffed-up male action heroes (Schwarzenegger, Stallone, et al) Aliens dared not only to scorn false machismo, but to weave a gory, violently thrilling story about motherhood. Critics and audiences responded with rapture. Sigourney Weaver earned one of the film's seven Oscar nominations (it won for Sound Effects Editing and Visual Effects) and the film owned the box office for four weeks. Aliens is one of the most-emulated films in action and/or science fiction, and arguably James Cameron's best work. We'll revisit some key memories of the film after the break.

I normally don't go in for the big nostalgia trip when looking back on the anniversary of a movie release, but Aliens was a serious experience for me. Star Wars infected me with a rabid appetite for all movies involving space. Two years later Alien was a real point of fascination when it was in release. But I was a seven-year old with protective parents and wasn't allowed to see the film. (Wandering into a theater still showing Alien while trying to see Superman: The Movie is a story for another time.)

Aliens was released just after my family moved from Napa, CA to Midland, TX. At 13, with high school looming just as I was feeling like I had a handle on the social basics, that move was a traumatic experience. I'd been depressed for some time before leaving. Midland's dry, forbidding geography, so different from Napa's gorgeous, pastoral landscape, was a daily reminder that I was way out of my element. When we got to Midland, however, I saw my first TV commercial for Aliens. I hadn't even known it was being released, thanks to the opaque walls of my self-indulgent little sadness cocoon. It was the first thing that excited me that summer, and really helped me get through those first few months where I felt lost in a very alien landscape. Fandom isn't just distraction. It can provide focus, when everything else in the real world seems far too blurry.

My relationship to Aliens fluctuates now, all these years and many viewings later. I'm as stunned as I ever was by the production design, and as forgiving as one can be to the actors in suits who were given only a few dozen frames at a time to perform as the swarming xenomorphs. There are times when I still have a gleeful response to the deliberately over the top dialogue of the Marines. Other times, I see the soldiers as unpleasantly cartoonish and want to throw the loudmouth Hudson (Bill Paxton) out of the closest airlock. One thing never changes: I can't stand the screaming of the orphan Newt (Carrie Henn, in her only screen role) and flash to the scream-recording session in Brian De Palma's Blow Out when I watch it now.

I'm never less than fascinated by the development, especially in this context, of the core 'motherhood' theme. The idea emerges right in the title screen, when the 'I' in Aliens emits light in a graphic designer's minimalist representation of celestial birth. Alien was characterized by H.R. Giger's gooey vaginal visions,and this title card promises a blinding counter-argument. Then the second shot of Ripley's sleeping profile fades into a shot of Earth, defining the heroine as Gaia/Earth Mother and establishing the motherhood theme within minutes.

The movie's anti-macho viewpoint doesn't take long to kick in, either, as female Marine Vasquez (Jenette Goldstein) is quickly established as the toughest soldier on the boat. And Ripley, once awakened from hypersleep, mostly looks grubby and tired. She's dressed down, counter to mid-'80s beauty standards. That is, until she demonstrates her skills with the power loader — doing a man's job, in the eyes of the nearby marines — and is handed a glamour shot for her efforts. "Where do you want it," indeed? She might as well ask, "how about I put this future-Reebok right in your ass?"

For almost twenty of Aliens' twenty-five years those who love the original theatrical cut and the proponents of the 1992 special edition (SE), which runs an additional 17 minutes, have argued over superiority. I greatly enjoy some sequences in the special edition. In particular, I like the 'business as usual' walk and talk between two colony managers on the planetoid LV-426, a sequence which now almost looks like an outtake from Avatar. But when it comes to final judgement, I consider the theatrical version to be superior.

I'll argue for theatrical over SE for two reasons. One: the theatrical cut is more trim and precise. I always appreciate those characteristics. While many of the extended scenes are fun from a geek point of view, I don't think they do enough to enhance the suspense or advance the story. (Take, for instance, the extended walkthrough of the Sulacco in the SE. As a fan of set design I love that footage, but it does nothing for the story but emulate the similar sequence introducing the Nostromo in Alien. Since most of the action in Alien takes place on the Nostromo, introducing it as a character makes sense. So little of Aliens takes place on the Sulacco — and most of those scenes are in the big loading bay — that we don't need the walkthrough.)

More important, though, is the addition of a scene in the SE in which we learn that Ripley had a daughter who grew and died while she was sleeping through the 57-year aftermath of Nostromo's dire mission. ("I promised I'd be home for her birthday," Ripley chokes. "Her eleventh birthday.") That scene represents a crucial branch in the thematic development of the two versions.

The Ripley of the theatrical release is a woman who, so far as we know, never had anything but her career. Rescuing and protecting Newt is an evolutionary step. The violence that follows is a visceral externalization of the transformation from woman into mother.

In the special edition, protecting Newt is Ripley's penance for sleeping through her real daughter's life and death. Both versions are powerful. There is a valid argument for the fact that the SE/penance version, being the originally intended story, is the 'real' one. In the end, both versions arrive at the same place: Ripley has earned and embraced her status as a mother. But I'll stick with my preference for the theatrical version. The transformation in that version is, to me, more elegant and powerful.

Regardless, the fact that we can (and should) argue over the interpretation of themes of motherhood in a sci-fi/action movie is (sadly) remarkable. Aliens, at 25, remains a landmark movie, and proof that genre film can be expansive, fertile ground, rather than a confining framework.