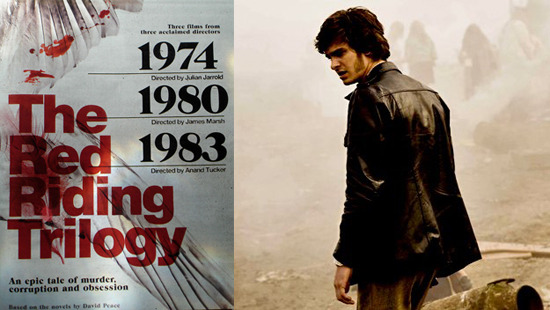

Weekend Weirdness: Red Riding Trilogy Reviewed (Britain's Five-Hour Answer To Zodiac?); New Trailers For Each Film

It's a crazy, mixed up world and we are thankful for movies, excluding The Spy Next Door and The Tooth Fairy, that offer proof. /Film's Weekend Weirdness examines such flicks, whether in the form of a new trailer for a provocative indie, a mini review, or an interview. In this installment, new trailers and a review of the Red Riding Trilogy, a noirish triptych of serial killer dramas imported from British television and being released stateside in February by IFC Films.

During a screening of the entire Red Riding Trilogy, with one intermission allotted for lunch, I found myself pondering the irony in three directors, one screenwriter, one author, tens of actors and three separate crews realizing a project that depicts humanity and bureaucracy at its most foul and irreversibly corrupt. A recent poster for the trilogy forebodingly reads, "Evil Lives Here," a tagline that would serve most of the work that exits Stephen King's skull; instead the "here" in Red Riding is Northern England in the '70s and early '80s, when a serial killer known as the Yorkshire Ripper carved a trail of female victims and set a mood and mythos ripe for social reflection.

If that sounds reminiscent of David Fincher's Zodiac, it is. Both that serial killer epic and Se7en are influential here by way of nightmarish imagery and the former's tediously realistic period detail and pre-computerized investigation routines. But it's much harder to seek comparison for the way the trilogy's storylines and characters—spread across three films, 1974, 1980, and 1983—communally bleed into each other, yet vary in quality, tone, and execution. The first film is a sexy, hardboiled mystery; the second a pitch-black procedural; the middling third a tale of redemption that borders on Hollywood melodrama. These differences make the trilogy appealing and slightly frustrating. Taken as a whole, it's a collaborative achievement that fans of crime cinema can feast upon.

In the Year of Our Lord 1974: Enough Cigarettes, Sex, and Murder to Make Andrew Garfield a Star

Rather surprisingly, the first installment of Red Riding has no less than four sex scenes, all of which feature 20something Brit actor Andrew Garfield. When he's not preoccupied in a bout of shagging, Garfield's mutton-chopped character, an ambitious newspaper journalist named Eddie Dunford, tends to have a cig and drink in hand. At first, it's difficult to gauge where the film is coming from, but Dunford's lifestyle choices are a youthful juggling act that blurs his well-meaning but naive obsession with a missing girl. He hopes to link the possible murder to two similar cases gathering dust and catch his big break.

In the proceeding two films, Dunford is a minor, peripheral character, but 1974 offers a star-making performance for Garfield, who will appear later this year in The Social Network. He portrays a young journalist drunk on romanticized, idealistic notions of the profession and still taps plenty of Raymond Chandler-like cool doing so. When the latest girl's body randomly surfaces, swan wings inexplicably sewn to her back, director Julian Jarrold (Brideshead Revisited) makes Dunford's hazy confusion our own, quickly plummeting us into a conspiratorial web of group-think involving the police, a powerful developer, elite society, and the media. Recurring themes of paternal betrayal and vacancy are planted beforehand, with Sean Bean as a delightfully sleazy yet dapper father figure-from-hell to Dunford.

Several readers have wondered if the Red Riding films work as stand-alone features—especially since they were originally made, and aired last year, for British television. Jarrold's 1974 works best in this regard. His use of 16mm in rendering a patina-heavy Yorkshire as a murderous landscape of pubs and misleading, at times ashen, hillside lends his film to memorable images. Dunford's tale is also the most singular and isolated—his noirish nighttime drives pay homage to David Lynch's Lost Highway—and the six-year gap between '74 and In the Year of Our Lord 1980 allows Jarrold to introduce several, complicit characters that are central later without worry for prior comparison. /Film Rating: 8/10

In the Year of Our Lord 1980: The Trilogy's Darkest Entry and the Critical Favorite

Set amidst a fictionalized investigation of the Yorkshire Ripper murders, 1980 is directed by James Marsh, who directed 2008's well-received doc Man on Wire. Compared to 1974, the protagonist in '80 is older and smarter, an experienced officer named Peter Hunter recruited to crack the stockpiling Ripper case (and who previously led an unsolved investigation of the bloody aftermath capping '74).

Whereas the look and tone of '74 mirrored the heady overindulgence turned paranoia of Garfield's Dumford, the style and pace of '80s plays on the sober career anxieties of Officer Hunter (played by In America's Patty Considine). Peter Hunter's rabbit hole is directly in front of him; he's the good man out amongst this new unit, but can't admit just how far. Of the three directors, Marsh has the most difficult task in bridging the films. He uses 35mm, lots of wide shots, and is font of framing Hunter in scenes to illustrate the Kafka-like labyrinth of bullshit—mundane and later sociopathic—he's up against.

Personally, I found Considine's officer to share a certain optimistic weariness reminiscent of Tony Blair walking into Bush's authoritative den of wolves; I'll also admit that certain scenes packed such hopelessness that I questioned the film's value of realism—and yet considered in mild horror whether the film's palpable anger was directed at actual records of police misconduct.

In watching Hunter re-examine the murder of a young girl wrongly (purposely?) attributed to the Ripper, I began to feel that 1980 too briefly touched on the serial killer's past crimes and terror. These films are not directly about the Ripper, but more exposition about him, and scenes with him, here would have been nice. Later I learned that the trilogy's source material was a quartet of books by British author David Peace (The Damned United); the second book, 1977, did indeed focus on the Ripper's spree. (It was left unfilmed due to budgetary restraints.) Knowing this, 1980 compensates for several gaps by featuring the trilogy's best ensemble performance and the bleakest if not wholly unpredictable twists and turns. /Film Rating: 7.5/10

In the Year of Our Lord 1983: Does the Director of Leap Year Stick the Landing?

I've chosen to highlight the stylistic differences and a few of the recurring themes for the prior two films since diving into countless supporting characters and their litany of motives would lead to spoiler-addled overlap. Thus far in critical circles, 1983 is being correctly cited as the trilogy's runt. What I found most puzzling was its rushed conclusion, which conjured so many soaring, slow-motion climaxes featured in the murder-thrillers that satiate Ashley Judd's Wal-Mart fanbase. If and when the Red Riding Trilogy—which I should add is subtitle free—is pointlessly remade by Columbia Pictures as planned, I doubt its ending will be this cliche.

Unlike 1974 and 1980, 1983 utilizes a lot of flashbacks (ones made for this installment), and also differs by spliting its focus between three men: a compromised police officer named Maurice Jobson (actor David Morrissey, who appears in all three and whose character changes the most between films—another point of debate amongst critics); a portly, unremarkable solicitor/attorney named John Piggott (Mark Addy); and a transvestite drifter named BJ (Robert Sheehan). All of these characters eventually cross paths after another young girl is abducted in Yorkshire. In a coiciding wave of panic, several police, including Jobson, consult a talented psychic. Quite a stretch. Suddenly the evil yet human foundation of the first films seems on the verge of being thrown out altogether.

Director Anand Tucker (the recently panned Leap Year) takes the most creative license, and for all of his entry's flaws and heavy-handed symbolism, his is still an interesting film. The material was certainly there for another director to stay within bounds and hit a deserved homerun, but the spirit of Red Riding encourages freedom for interpretation. And perhaps some of the blame for '83's ill-fit should be shared with screenwriter Tony Grisoni, who adapted all of them. Part of what makes Red Riding so captivating is the creative risk in loose and ambitious collaboration, and it's the resulting three uniquely haunting versions of a Yorkshire-in-decline that loom over arguments for more traditional consistency. /Film Rating: 5.5

/Film Rating: Entire Trilogy: 7Hunter Stephenson can be reached on Twitter. If you'd like to send him a screener, or a screening invitation, email him at h.attila/gmail. For previous installments of Weekend Weirdness, here.