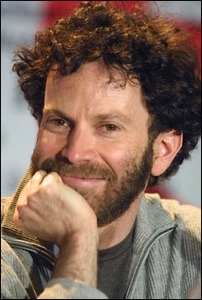

Interview With Charlie Kaufman

In September, I had the opportunity to sit down with Charlie Kaufman, the screenwriter behind Being John Malkovich, Adaptation, Eternal Sunshine and his directorial debut – Synecdoche, New York. Interviewing Charlie Kaufman is like playing a tennis match that you just can't win. I went into the interview with questions about symbolism and themes, but one of the first things he said was that he doesn't want to talk about the meaning of the film. And that's fine. So the interview became more about the process of screenwriting and the transition into directing, than it did about the movie itself. Synecdoche, New York will be in a few theaters beginning this weekend.Peter Sciretta: Do you typically write your films hoping that audience will require multiple viewings?

Charlie Kaufman: Yes. Well, I think it makes it more interesting for an audience to have some complexity in the material, and also, I've got this sort of thing where I'm trying to make it feel like it's a living piece of theater, as opposed to a set, sort of a pre-recorded thing. And it's sort of a tricky thing to try to make film feel alive because it isn't. So this way, it can change when you watch it again at a different point in your life, or just seeing it for the second time, you're going to see things you couldn't possibly see the first time because you didn't know something until the end. But, also, you get to look at details. You can watch things that are happening in the background of scenes that are informative that you probably don't see the first time through when you're just trying to get the thing. So that's why.

Peter Sciretta: I've talked to a lot of people that they have that moment of realization or something a week or two after they see one of your films.Charlie Kaufman: Yes, well, I mean I've heard that with this movie, in particular, that people tend to have a delayed reaction, that it sort of sits with them and becomes more affecting over time, which is kind of nice for me to hear that there's a continuing relationship with the work in someone's brain. It's still processing over time. I think most movies aren't designed to do that; they're designed to get people into the box, into the theater on the opening weekend and make a lot of money. I guess it's kind of an unfortunate sort of direction for something that's an art form, or it should be or can be.Peter Sciretta: What are the origins of Synecdoche?Charlie Kaufman: I started to talk with Spike Jonze. We were going to do a horror movie for Sony, and we were talking about, well, what's really scary rather than what horror movie conventions are that were scary. So we were talking about aging and dying and illness and family and loss and regret and loneliness and kind of went in to Amy Pascal and just pitched a kind of a general sort of direction, and she just wanted to work with us because we'd done adaptation there, and she liked us. So she told me to go off and write it, and I did. And it took me a few years to write it, and then Spike had become involved with Where the Wild Things Are, and I asked him if he would let go of it so that I could direct it, and he said yes.

Peter Sciretta: What made you to want to direct this film? You've written a lot of films for Spike that show...

Charlie Kaufman: I haven't really written any films for anybody, I mean in a literal or a figurative sense. I mean I wrote Being John Malkovich before I even knew who Spike Jonze was. He just happened to be the person who could get it made and wanted to make it. I wrote Human Nature before I knew who Michel Gondry was. I wrote Eternal Sunshine based on Michel approaching me with a notion, but I didn't think of myself as writing it for him. I don't think of myself as writing things for directors. I do what I do. They do what they do. I consider myself their equal. I don't care if they consider me their equal. I don't think there's a hierarchy. As a writer, I think I do a very different job than a director, and vice versa. For some reason, the job of writing is considered a lower thing in movies than directing. I don't quite understand why.

Peter Sciretta: It's a shame. I mean...Charlie Kaufman: I mean it's weird. It's very specific to movies. It's not true in television. The people who run the shows in television are writers. The person who's the most important person in a play is the writer. The directors are hired, but writers own the material. Nothing can be changed without the writer's permission, that kind of thing. Then for some reason, there's this thing that goes on. But, anyway, I digress.Peter Sciretta: Some films, writers aren't even allowed on the set, right?

Charlie Kaufman: Well, they're not allowed on the set. They can be replaced. They are replaced all the time. I mean the bottom line is the reason that this thing has evolved this way is because writers are not important to movies. And by not important to movies, I mean they're not important to the commercial success of the movies. You have movies that are terribly written by 50 people that get terrible reviews that make $200 million their opening weekend, you know? You have movies that are written really well by one person that can't open, and so the people who make these decisions decide, "Well, we don't need writers. Fuck 'em." And, unfortunately, they've turned out to be right because that's what people don't care about.

Peter Sciretta: Well, people do care about the name value of some directors. There's more name value in directors.Charlie Kaufman: There is, and that's sort of been perpetuated by this auteur theory, which I find enormously bizarre considering that the word auteur means author. And, indeed, the only person who's the complete inventor of the movie is the writer. The director's interpreting material. Actors are interpreting material. Everybody's interpreting the script. And I'm not saying that the writer is more important than the director or other people, but I'm saying the writer needs to be given his or her due in the process. Peter Sciretta: So is is entering the directing medium a way for you to be considered more of an author?Charlie Kaufman: No, it's my work, and so it's a way to take my work from in my brain to on a piece of plastic in a movie theater, and that gives me control of the process in a way that I don't have even though most directors I've worked with have been really lovely and really collaborative with me, and I'm very happy with the movies that we've done together, but I wanted to do this. It's not like a new thing for me. I went to film school. I spent a lot of time in theater and acting when I was a kid. It was my passion. I mean I have that background, I have that interest in it, and I've wanted to direct. And then I got to a point where it was feasible that I could get that job, so I took the opportunity and did it.Peter Sciretta: Is directing something you're looking to continue?

Peter Sciretta: So is is entering the directing medium a way for you to be considered more of an author?Charlie Kaufman: No, it's my work, and so it's a way to take my work from in my brain to on a piece of plastic in a movie theater, and that gives me control of the process in a way that I don't have even though most directors I've worked with have been really lovely and really collaborative with me, and I'm very happy with the movies that we've done together, but I wanted to do this. It's not like a new thing for me. I went to film school. I spent a lot of time in theater and acting when I was a kid. It was my passion. I mean I have that background, I have that interest in it, and I've wanted to direct. And then I got to a point where it was feasible that I could get that job, so I took the opportunity and did it.Peter Sciretta: Is directing something you're looking to continue?

Charlie Kaufman: Yes, I think now that I've done it, I know I can do it. I know I did do it. I think I learned a lot. I think that will be reflected in my next thing. I don't mean reflected in the result; I mean reflected in my experience of directing. I feel like I'll go in with the experience of directing a movie before and bring all of that to it, and I like it. And the idea of going back and giving things over and losing the control that I now feel like I had doesn't appeal to me. So if I can, if people will let me direct my work, I will continue to do it.

Peter Sciretta: What is this movie about to you?Charlie Kaufman: Well, I do make it a point of not explaining the work that I do because I think that my goal when I do something is to have a conversation with the audience rather than to lecture them, and I think that what that means is that I want an interaction with people, and I want people to respond to the movie, and if I sit here and say, "Well, this, to me, means this, and this means..." I mean it means what it means, and it means what you think it means, and it means what somebody else thinks it means. And it is what it is, as opposed to even necessarily meaning anything. It's the experience of watching it. I read this quote. I can't remember who it was. It was a composer who had written — famous, but I can't remember now who it was — who'd written a piano piece and played it, and afterwards, somebody was standing there and said, "Well, but what does it mean?" and he sat down and played it again. That was his answer. What does it mean? This is what it means, you know? Peter Sciretta: What's the transition like going from screenwriting to directing? What were some of the difficulties that you found?Charlie Kaufman: I think the major kinds of issues with directing are that it's mired in pragmatism in a way that writing isn't. You need to figure out how to spend your money in a way that is most effective, and everything is based on what you can and can't afford, everything–the number of days that you have, the number of sets that you have, the number of extras you can afford. Constantly, every moment of every day is, "How do we do this? How do we afford this? How do we afford this make-up? How do we schedule this make-up into this day? How do we do these things that we need to do, but they're in three different locations and we can't move the crew because we're going to lose hours by doing that, so how do we reschedule this?" It's a lot of that, and it's very different than writing, which is you're sitting in a room thinking of the best thing you can think of, and there's no monetary concern, and there shouldn't be.Peter Sciretta: When you're sitting there and you're writing, and you're like, yes, warehouse with a scale model of New York City...Charlie Kaufman: Exactly. And the problem is now that I've directed and I've faced the issue, I don't want to go into writing thinking, "Okay, I need to do a warehouse with New York in it, but that's impossible, so I'm not going to write that," you know? I want to kind of let go of that and go back to the other job. And then we figured it out. We had a limited budget. We figured out how to do it, and that's pretty impressive because there are an extraordinary number of special effects in this movie.Peter Sciretta: Definitely. I heard your original draft had something like 250 scenes.Charlie Kaufman: I don't know. I think we ended up with 204 scenes. We shot 204 scenes. I don't know what the original draft was. The original draft was about 20 pages longer than the production draft, so I'm assuming maybe, yes, we couldn't have that many more scenes.Peter Sciretta: Was there anything that you really missed having to give up because of the budgetary constraints?Charlie Kaufman: Not really. I mean there's stuff that we lost along the way, but I felt like it was stuff that we could lose. I mean there was a through [ph?] line with an animal that the character of Hazel finds on the side of the road who's been– the dog's been squashed and he's going to die, and she takes it home, and it ends up living throughout the rest of the movie. So we shot this stuff, and we had the dog, and we had it marked so that we could effectively put a tire track through the dog, a living dog, every time you saw it. But that was more of like a time thing. It was more like we needed to condense the movie a little bit. I had another character, another woman, in the movie who was a young French film student that Kaden [ph?] meets in Berlin and has a bit of a relationship with, non-sexual, but a kind of a little day with flirtation, and that was one of the first things that had to go, and I had to tighten the script. I really liked that character, but the movie was too long to shoot.Peter Sciretta: You had to kill your baby.Charlie Kaufman: Yes.Peter Sciretta: What are you working on next?

Peter Sciretta: What's the transition like going from screenwriting to directing? What were some of the difficulties that you found?Charlie Kaufman: I think the major kinds of issues with directing are that it's mired in pragmatism in a way that writing isn't. You need to figure out how to spend your money in a way that is most effective, and everything is based on what you can and can't afford, everything–the number of days that you have, the number of sets that you have, the number of extras you can afford. Constantly, every moment of every day is, "How do we do this? How do we afford this? How do we afford this make-up? How do we schedule this make-up into this day? How do we do these things that we need to do, but they're in three different locations and we can't move the crew because we're going to lose hours by doing that, so how do we reschedule this?" It's a lot of that, and it's very different than writing, which is you're sitting in a room thinking of the best thing you can think of, and there's no monetary concern, and there shouldn't be.Peter Sciretta: When you're sitting there and you're writing, and you're like, yes, warehouse with a scale model of New York City...Charlie Kaufman: Exactly. And the problem is now that I've directed and I've faced the issue, I don't want to go into writing thinking, "Okay, I need to do a warehouse with New York in it, but that's impossible, so I'm not going to write that," you know? I want to kind of let go of that and go back to the other job. And then we figured it out. We had a limited budget. We figured out how to do it, and that's pretty impressive because there are an extraordinary number of special effects in this movie.Peter Sciretta: Definitely. I heard your original draft had something like 250 scenes.Charlie Kaufman: I don't know. I think we ended up with 204 scenes. We shot 204 scenes. I don't know what the original draft was. The original draft was about 20 pages longer than the production draft, so I'm assuming maybe, yes, we couldn't have that many more scenes.Peter Sciretta: Was there anything that you really missed having to give up because of the budgetary constraints?Charlie Kaufman: Not really. I mean there's stuff that we lost along the way, but I felt like it was stuff that we could lose. I mean there was a through [ph?] line with an animal that the character of Hazel finds on the side of the road who's been– the dog's been squashed and he's going to die, and she takes it home, and it ends up living throughout the rest of the movie. So we shot this stuff, and we had the dog, and we had it marked so that we could effectively put a tire track through the dog, a living dog, every time you saw it. But that was more of like a time thing. It was more like we needed to condense the movie a little bit. I had another character, another woman, in the movie who was a young French film student that Kaden [ph?] meets in Berlin and has a bit of a relationship with, non-sexual, but a kind of a little day with flirtation, and that was one of the first things that had to go, and I had to tighten the script. I really liked that character, but the movie was too long to shoot.Peter Sciretta: You had to kill your baby.Charlie Kaufman: Yes.Peter Sciretta: What are you working on next?

Charlie Kaufman: I don't know. Trying to come up with an idea.

Peter Sciretta: The other thing I want to talk to you about, the film is so fantastical in many ways, but it still is able to seem grounded in reality.

Charlie Kaufman: Good.

Peter Sciretta: Is that something you were striving for?Charlie Kaufman: Yes, always. I'm always striving for that in everything I do. It's like those sorts of surreal things and flourishes are not the basis of the movie. I mean they're integral to expressing certain things, but every emotion is a real emotion. And that's how I work when I'm writing it, and that's how I work with the actors, and we placed ourselves in those moments when they performed them, as if this were reality, and the issues are real issues to me.Peter Sciretta: Okay. Well, thank you very much, Charlie.Charlie Kaufman: Thank you.