This Alfred Hitchcock Crime Thriller Was Once Banned In A Major U.S. City

Alfred Hitchcock might be the most famous director to ever live. His name is synonymous with the word "suspense," having crafted some of the finest motion pictures of all time, but the acclaimed director was plenty controversial during his lifetime as well. His horror masterpiece "Psycho" was accused of being needlessly violent and sexually perverse, but his most controversial film might be a surprise for anyone who isn't well-versed in his long filmography.

Hitchcock's 1948 crime thriller "Rope" was seen as something of a lesser entry before having a critical reevaluation over the last decade. It was mostly known as a footnote for being Hitchcock's first Technicolor film and its unconventional production. Based on the true story of two Chicago students who similarly attempted to get away with "the perfect crime," Hitchcock decided to tell the story in real time, stitching together several long takes to give the appearance of a film that never cuts away from the action. Perennial Hitchcock favorite James Stewart stars as the boy's prep school housemaster and voice of morality, who the boys put to the test.

The film was remarkably controversial, even by Hitchcock's standards. It faced heavy pressure from film censors during the era of the Production Code that enforced a harsh and arbitrary set of rules against anything deemed amoral, and when it finally screened in theaters, censor boards in Seattle, Atlanta, and Memphis banned the film from being screened in their respective cities. The New York Times reports that "Rope" had already played for a day at Seattle's Orpheum Theater before censors banned future screenings, while in Chicago, the police "barred the picture on the grounds that it was not 'wholesome' entertainment." Warner Bros. was able to appeal the decision and bring the picture back in theaters as an "adults only" film, but the question of why the film proved to be so controversial still lingers for Hitchcock fans who are rediscovering the film today. There are three primary reasons why, two prominently on display in the film's opening moments and one hidden subversively in the subtext.

Censors balked at Rope's graphic violence, the characters' heavy drinking, and flippant amorality

During this period of film history, the Motion Picture Association of America had a heavy hand in shaping what content was deemed acceptable to depict in film. Despite his stature in the film industry, Hitchcock was beholden to these censors just like everyone else, and historian Katie Reid details exactly how "Rope" ran afoul of these censors in her piece for Screen Culture.

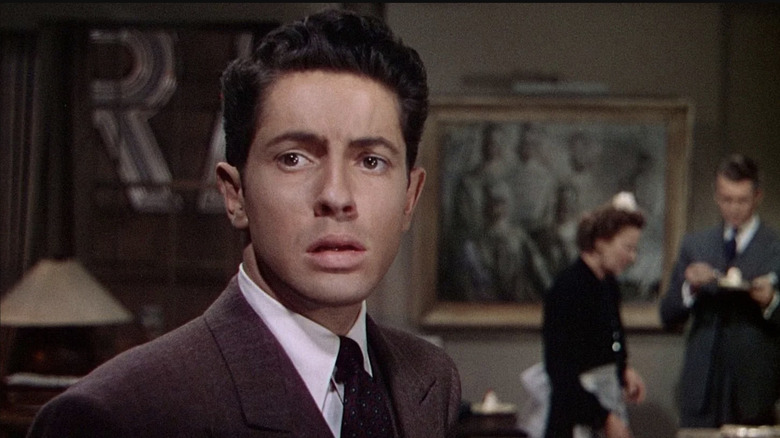

"Rope" opens with its two villains, Brandon Shaw (John Dall) and Phillip Morgan (Farley Granger), strangling their former classmate David Kentley (Dick Hogan) to death in their home in an act of casual cruelty. It's an astonishingly brutal opening to a film, even by Hitchcock's standards, and the film censors objected to it immediately.

Hitchcock adapted the script from a play based on Leopold and Loeb's story, and film censor Joseph Breen quickly singled out the story's disturbing violence and its "very specious but well-written speeches in which fundamentally moral values are denied and even made to look ridiculous." He also singled out sections where "the Ten Commandments were treated harshly and advised those pieces of dialogue to be taken out as they would be a 'great offense to motion picture audience.'"

Hitchcock assured these censors that the film would not endorse the killer's actions, but the censors still tried to force Hitchcock to remove the opening murder scene entirely, including a moment where Brandon wipes his fingerprints off a glass, fearing that this could serve as a "How To Get Away With Murder" guide for audiences.

But what the film board was most concerned about was even more mundane by today's standards: alcohol. Throughout the script, Phillip drinks champagne to calm his nerves, and Breen requested "it be kept down to a degree necessary for characterization or plot motivation." Even if the Prohibition Era had ended a decade prior, the depiction of alcohol in film was still fraught, and Hitchcock was able to prove that the use of alcohol was absolutely necessary for telling his story.

But these concerns would pale in comparison to the greatest taboo that Hitchcock would explore, which turns out to be its biggest lasting legacy.

Rope's subversive queerness lingered as subtext censors didn't pick up on until it was too late

Lurking as subtext throughout "Rope" is the relationship between its two killers, Brandon and Phillip. These two are more than just roommates, and the film heavily implies a homosexual relationship between them. This aspect of the film slipped past the censor's view for much of the film's production, until a letter sent by Breen explicitly forbade Hitchcock from exploring this aspect of the characters:

"We also got a possible flavor in some of the dialogue that a homosexual relationship existed between Brandon and Phillip. This was heightened somewhat by the fact that there is some degree of similarity between these two characters and Leopold and Loeb [the real killers who inspired the film] ... such a treatment could not be acceptable under the terms of the Production Code."

Hitchcock played dumb about these homosexual undertones, but behind the scenes, he did everything he could to amplify them. He hired gay screenwriter Arthur Laurents and cast Laurents' lover, Farley Granger, in a lead role. Hitchcock reportedly was delighted to "hide a secret gay love affair within his film," even if it led to intense scrutiny from his bosses at Warner Bros.

He was able to push "Rope" through production, more or less intact, but the ensuing controversy took on a life of its own. Deeming the film viciously amoral, film censors in conservative pockets throughout the country refused to allow the film to be distributed, with several censors demanding the strangulation scene be removed from the picture.

The New York Times notes that this "peculiar" censorship comes after the film was deemed "morally unobjectionable for adults" and that "there have been no pronounced objections voiced by religious groups," which suggests these censors took it upon themselves to ban the film. Looking back on it now, perhaps these censors picked up on the film's subversive and queer elements, even if they couldn't quite put their finger on it, so they used the film's supposed violence as a scapegoat to justify censorship.

Luckily, their attempted repression failed to stop the film from playing elsewhere, and it's now regarded as not just Hitchcock's experimental masterpiece, but as one of the greatest subversively queer films of all time. As political repression on the arts makes its way back into the mainstream, this is a hopeful reminder that censorship is no match for an artist's creative ingenuity.