The Downfall Of The Alien Franchise Can Be Traced Back To One Moment

Before I begin, I should establish with readers that I vastly prefer Ridley Scott's 1979 sci-fi horror film "Alien" over James Cameron's high-octane action-packed 1986 follow-up "Aliens." Heck, I even prefer David Fincher's strange, awkward prison tragedy "Alien3" over "Aliens." While Cameron's film is slick and exciting, the "Alien" series — for me — has always functioned better when it hovers in the realm of terror, fear, and death. The alien Xenomorphs, designed by Swiss surrealist H.R. Giger, are better movie monsters when they are ineffable, strange, and off-putting. The title of Scott's film is both a noun and an adjective, describing a biological horror that the film's human protagonists can barely understand.

When standing in front of a Gigerian nightmare from beyond the stars — one made of aspic, teeth, and remixed human genitals — one shouldn't be holding a gun shouting clichéd movie dialogue like "Let's rock." For this author, "Aliens" is the least interesting approach to an "Alien" sequel. I understand this is a very unpopular opinion, of course, but I shall stand firm.

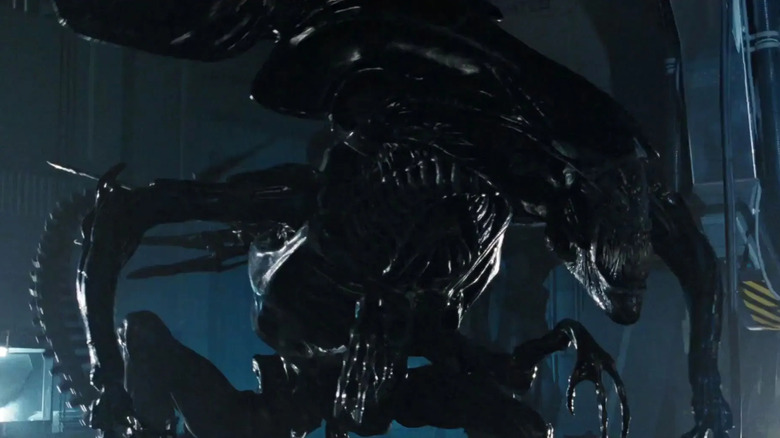

It will also allow the reader to understand what I mean when I declare that the introduction of the Alien Queen in "Aliens" was the "downfall" moment of the series. Prior to that, the titular creatures were terrifying and beyond understanding. With the introduction of a Queen, the Xenomorphs became a little too understandable. They became a mere problem to be dealt with. In "Alien," there was no way to hurt the monster, no way of conceiving what it wanted or how it functioned. Its mystery made it scary. The Alien Queen was a semi-intelligent animal that was very clearly protecting its young. It had a palpable animal intelligence, and seemingly got angry when threatened. And, yes, if one had enough bullets or a badass power loader suit, the Alien Queen became something that could be strangled and shot into oblivion.

The Alien Queen became a video-game-like boss monster, and made the monsters less scary. An unpopular opinion, of course, but salient if you, like me, prefer horror over schlocky action.

The Xenomorphs used to be strange and nightmarish

Recall how strange "Alien" must have seemed in 1979. The alien Xenomorph has been re-used in so many sequels, crossovers, comic books, and arcade games that it now seems commonplace. The reproduction cycle of the Xenomorphs is also now commonplace, and takes no time at all; it was a mere background detail in "Alien vs. Predator." There was a time, though, when the creature was so strange, it boggled the mind. Giger designed the monster after his painting "Necronomicon IV," an upsetting work that featured a humanoid figure with an elongated head and a massive phallus. The alien was no mere monster, but something out of a dream, so very ... well, alien. And the reproduction cycle was once terrifying.

The creatures begin their inside leathery eggs as knuckle-like crab/centipedes. They leap out of the eggs and wrap themselves around the faces of potential hosts. Over the course of a few days, the facehuggers ram an ovipositor down its host's throat and implants a fetus in their chest cavity. Once that is done, the facehugger dies. The fetus spends a short while growing inside its host, eventually breaking out — directly through skin and bone — when it reaches a certain size. It quickly grows to seven feet in height, and is driven by a murderous impulse. It kills when it reproduces, it kills when it's alive.

In the director's cut of "Alien," it also has an eerie way of continuing the Xenomorph life cycle. It can kidnap humans, cocoon them against a wall in a sac of fetid slime, and use ineffable acids to break down their bodies. The slime will slowly encase them, breaking down their bones and guts into ... more facehuggers. Humans become the new eggs. Once the eggs had formed, I got the impression that the Xenomorph would die; its lifespan, like an insect, was only a few days.

The Alien Queen makes the Xenomorphs less threatening

But because that scene was cut from Scott's film, Cameron was allowed to rewrite alien biology for "Aliens," and his approach was much less creative. He posited that the Xenomorphs were like ants, and that there was a Queen that laid all the eggs. The Queen was designed to have a big, angry mouth, making it more human and expressive. Some will point out that a deleted scene in "Aliens" posited that Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) learned she had a daughter back on Earth who had died while Ripley was in cryogenic stasis. This would explain why Ripley had such a matronly connection to Newt (Carrie Henn), and set up a thematic battle between her and the Alien Queen at the end. They were both mothers protecting their offspring.

This, however, isn't a terribly interesting theme. The Alien Queen, unlike the creature in "Alien," now had a knowable, easy-to-understand motivation. It even seemed to have emotions, and made decisions based on those emotions. It also seemed to be the "final boss" in a movie all about blasting and exterminating creatures. Once the "big bug" is killed, the nest is taken care of and everyone can go home. A character calls their mission, dismissively, a "bug hunt." It seems the ineffable nightmares of deep space are now just chores for the Marines.

And, moving forward, the "Alien" series became instantly less scary. Cameron made the aliens too understandable, too human. These things shouldn't have motives and emotions, however animal they should be. But because "Aliens" was a massive success, we're stuck with Cameron's action-packed ideas in perpetuity.

"Aliens," in its structure, is no different from a film like "Mouse Hunt." Both films are about people going into a dangerous place infested with an unexpectedly intelligent creature. "Aliens" may be badass, but badass is boring. Give me the unknowable chaos of the cosmos over cheesy power loader suits any day.