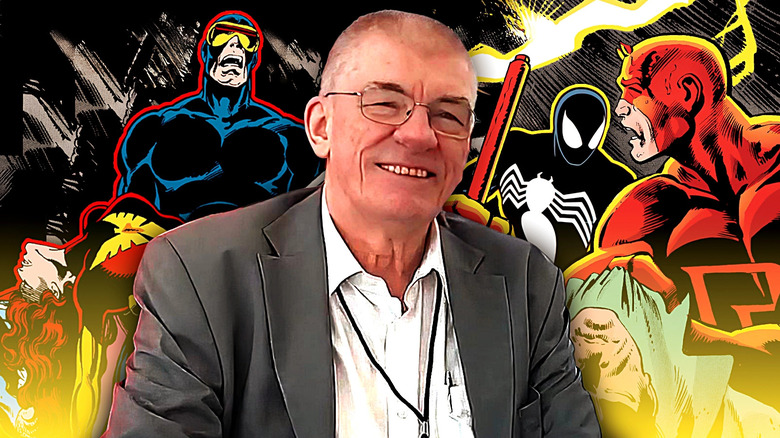

The Best Marvel Comics Era Was Overseen By Its Most Controversial Editor

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Comic book legend Jim Shooter died on June 30, 2025, at the age of 73. Primarily a writer/editor, Shooter's career was incredible ... right from his, to use the superhero phrase, secret origin.

Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Shooter started writing for DC Comics (then officially known as National) at age 14. He sent in some stories about Superman and the Legion of Superheroes, and soon DC editor Mort Weisinger not only bought them, but he also hired Shooter to write the Legion's adventures full-time. How did Shooter work up the courage to submit stories when he wasn't even out of high school? It wasn't whimsy, it was desperation; he and his family were living in poverty and he thought writing comics would be an easy way to get them some needed extra cash.

To prepare himself, Shooter studied the craft of Stan Lee's Marvel comics, because he thought Marvel's stories were far superior to DC's.

"I got the idea that if I learned to write like this Stan Lee guy, I could write for these other turkeys, DC, because they sure needed the help," recalled Shooter in a 2010 interview. Little did Shooter know that, one day, he would literally have Lee's job as Marvel's editor-in-chief.

In 1978, Shooter became EIC of Marvel Comics and stayed in the role until 1987. Shooter's reign was a period of great success for Marvel; he's probably the most important editor-in-chief the company ever had besides Lee. Similar to Lee's own controversial legacy, though, not everyone working at the company thought of Shooter as their own superhero.

When Shooter took the job, Marvel was at a low point. Lee left the EIC position in 1972, and it became a revolving door of journeyman writers trying their best to do the job: Roy Thomas, Len Wein, Marv Wolfman, Gerry Conway, and then Archie Goodwin. In Shooter's first month on the job, Marvel only shipped 26 of the 45 comic series it had planned to. His task was getting the company back on track, and he succeeded while also angering many writers and artists with his strict management style.

Remember, Shooter was reared in comics by Weisinger, who was, in Shooter's own words,"mean as a snake at his nicest." In Sean Howe's "Marvel Comics: The Untold Story" by Sean Howe, Shooter's section in the book's index has a whole subhead for "conflicts between artists and writers." But do the results of his EIC tenure speak for themselves?

Jim Shooter's controversial legacy at Marvel, explained

One of Shooter's earliest policies was to institute strict deadlines for Marvel writers and artists. (Writer Steve Gerber, for example, was removed from "Howard the Duck" because he couldn't meet deadlines.) In 1978, Shooter also got the unenviable job of demanding Marvel's writers and artists sign a new "work for hire" contract in accordance with changing copyright law.

As Shooter noted years later, "The new copyright law had been enacted in 1976 but took effect in 1978, giving publishers TWO YEARS to prepare. Marvel, of course, had done NOTHING." He thus became the bad guy in a lot of writers and artists' eyes for handing them the paper.

Howe writes that Shooter "expanded the editorial staff but siphoned power from the Bullpen" at Marvel, meaning he concentrated more power over the writers and artists among his editorial staff. He wielded that power to intervene in storytelling. In 1980, Chris Claremont and John Byrne's "X-Men" had reached what's now called "The Dark Phoenix Saga." Psychic X-Woman Jean Grey grows powerful beyond belief and loses control of herself — in "X-Men" #135, she consumes an entire star, killing billions.

Claremont and Byrne intended that Jean lose her powers in the end. Shooter wasn't having it: "That, to me, would be like taking the German army away from Hitler and letting him go back to governing Germany."

So, when Claremont (not seriously) suggested killing Jean instead, Shooter said yes. He defended his actions because "the [editor-in-chief] is charged with governing, managing, and protecting all of the characters. It was my job to make sure the characters were in character, and I was the final word on what 'in character' was."

Shooter was right; "Dark Phoenix" is a more powerful story because Jean dies. Not all of Shooter's interventions were so great, however. His "Avengers" #200 infamously features Carol Danvers being brainwashed to love a being named Marcus and becoming pregnant with Marcus' infant self. Yes, Ms. Marvel gives birth to her rapist. Claremont was so appalled he wrote a rebuttal in "Avengers Annual" #10, where Carol excoriates the Avengers for not helping her.

Like Stan Lee, Shooter had a strong commercial instinct. He credited Marvel publishing "Star Wars" tie-in comics (and, in turn, printing money) in the late 1970s as the reason the company had survived a rough period. So, as EIC, he supported similar partnerships and sponsorships. For example, Shooter's 1984 12-issue series "Secret Wars" (drawn by Mike Zeck and Bob Layton) was all to promote a toyline of Marvel Comics action figures produced by Mattel. In the 1980s, Marvel also became the publisher of tie-in comics for Hasbro action figure lines. (Shooter himself wrote the original story treatment for "Transformers.") More insidiously, he also maintained a ban on Marvel comics featuring gay characters.

Shooter could also have a blunt sense of humor. In 1984, he sent a memo to his editors stating:

"Effective immediately start doing good comics. I realize that this directive reflects a substantial departure from previous company policy, but please try to comply."

But the thing is, they did comply. Shooter had a great talent for spotting talent, and under his tight management, some of the greatest Marvel comics ever written and drawn hit newsstands.

For Marvel, the Bronze Age of Comics was a Golden Age

Howe describes Shooter's ideal Marvel comics (exemplified by Shooter's own "Avengers" run) as "banter-heavy dialogue and small medium-shot panels that showcased the colorful costumes, all adding up to a staccato rhythm of adventure and whimsy." But that's far from all the company was publishing.

Shooter's EIC tenure is when the X-Men (under Claremont) and Daredevil (under Frank Miller) became bestsellers. Claremont drew readers to "X-Men" with both verbose soap opera plotting and stories of social relevance. Meanwhile, John Byrne, a superstar artist from working on "X-Men," jumped over to write and draw a legendary run on "Fantastic Four."

Miller turned "Daredevil" into, as Jeremy Dauber puts it in "American Comics: A History," a noir movie with the action of a manga. Shooter is the one who had first hired Miller as a penciller on "Daredevil," because he had faith that both the character and Miller could be something great. How right he was.

Some of Shooter's other hires included Mark Gruenwald as his assistant editor (who went onto pen a titanic 100+ issue run on "Captain America"), Louise Simonson (writer of "X-Factor" and creator of Apocalypse), and Larry Hama (who wrote the "G.I. Joe" tie-in comic from 1982 on, transforming a toy advertisement into a creator-driven book). Shooter wasn't a complete firebrand on creator rights, but he did work to let his people share in the money they were making Marvel.

In 1981, DC's President Jenette Kahn launched a royalty program for comic writers and artists in which they would get a 5% cut of each issue's revenue after 100,000 issues were sold. Shooter launched a similar "incentive" program at Marvel. As Howe notes, practically every series Marvel had was selling more than 100,000 monthly, so many writers and artists made cash over fist.

Shooter's reputation as a company man isn't baseless, but I think he shows the brighter side of that description. He understood that part of running a good company is making talented people want to work for you. Shooter himself said as such in a 2017 interview with AIPT: "How you get better people is with incentives."

Even if his storytelling instincts could be commercial, they weren't wrong. One of his critiques of modern comics, that they've gotten away from single issue stories (see the AIPT interview), is spot-on and a big reason Marvel Comics today struggles to attract new readers. When Shooter was Marvel's EIC, he followed Lee's model that every issue should be written as if it is someone's first.

Christopher Priest, a comic writer and former Marvel editor, described Shooter as "a genius" and "a kinder, gentler, smarter, more touchy-feely version" of the similarly efficient Weisinger in a 2002 blog post:

"Jim was very good at being the boss. He certainly knew his stuff and he knew how to move projects from "A" to "Z." [...] Jim made deals and threw money at people who couldn't stand him. [...] He didn't care about being the heavy: somebody had to be the heavy. But, for Marvel to survive and grow, the kids would have to grow up. And Shooter became the avatar of our painful adolescence."

Jim Shooter's legacy is more complicated than the pure-hearted superheroes he wrote, but he was the hero Marvel needed. May he rest in peace.