Sinners Finally And Violently Flushes Anne Rice And Twilight Out Of The Modern Vampire Movie

This article contains spoilers for "Sinners."

I've never met a vampire movie that I didn't like, but not all vampire movies are created equal. In the beginning, vampire myths served as cautionary tales warning people about supernatural, often undead creatures that feast on vital essences, most notably — blood. Folk stories about the creatures have been recorded in cultures across the world, but the term "vampire" gained popularity in Western Europe during the 18th century, when mass hysteria took hold that resulted in corpses being staked through the heart and living people lynched after being accused of vampirism.

This inherent "othering" meant the majority of the ways vampires have been depicted tend to fall into two categories: an allegory for "otherness" (aka strangers to fear) and misunderstood outcasts thrust to the margins by a panicky society. Add this in with the seductive sophistication of vampire literature published in the 19th century, and you've got the building blocks of every vampire depiction from the grotesque "Nosferatu" to the cheeky ballerina vampire, "Abigail." In recent years, the romantic (if not a straight-up vessel of forbidden sexual intrigue) vampire has reigned supreme, like the Anne Rice vampires of "Interview with the Vampire" (both the film and the criminally underseen AMC series) or the Mormon-soaked yearning of Edward Cullen in the "Twilight" series. There's an allure to these brands of "other," where giving yourself over to the danger is half the fun.

In Ryan Coogler's breathtaking new movie "Sinners," the vampires are not tragic figures or agents or allegories for the way the status quo demonizes oppressed communities, but instead a genuine hazard of infiltration and assimilation. And for once, they're reflections of the real people who engage in the essence-stealing behavior in real life.

Vampirism as agents of manipulation

While the "rules" of vampires are completely made-up (because they're not real), one of the most common is that a vampire cannot enter a space without being invited in. It's a symbolic barrier, one that presents the home as a sacred space and sets up would-be victims as responsible for their own demise. The mindset is that if you invite the vampire inside, you only have yourself to blame, providing a pathway for vampires to avoid accountability. It's the same mindset lobbied against victims of theft (that's what you get for parking on the street) and survivors of sexual assault (if you were wearing that skirt, you were asking for it).

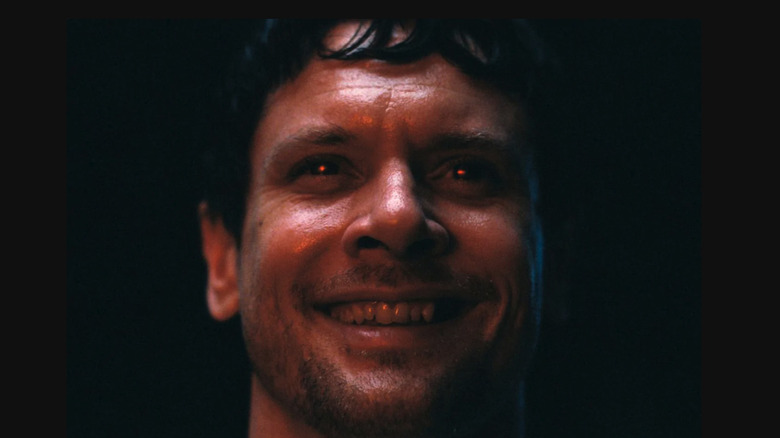

In "Sinners," the vampires are led by Remmick (Jack O'Connell), a white vampire who seeks solace in the welcoming home of two members of the Ku Klux Klan after they completely ignore the warning provided by a group of Indigenous people not to let him in. It's a fantastic introduction because it immediately twists our belief system on its head. We know it's wrong to victim-blame, but ... these "victims" really do only have themselves to blame because they let racist thinking control their decisions. Once Remmick has turned the couple, the trio is drawn to the Juke Joint by the force of the music Sammie (Miles Caton) plays, intending to steal his power to enact their personal brand of evil.

They try in vain to get into the club on their own, but once it's clear that the Black-run club is not letting these weird white folks in, the vampires target the white-passing Mary (Hailee Steinfeld) and use her as their ticket in. They may not be able to enter the club, but Mary can, and she can infiltrate and turn other people on the inside for them once they've turned her into a vampire. Using Mary to manipulate her community, her family, is diabolical. The threat of the vampire is real, and it will destroy you from the inside out if given the chance.

Vampires as allegories for racism

American society tends to make anyone who falls outside of the white, cisgender, heterosexual, male, Christian identity feel like a monster. In Brad Michael Elmore's intersectional feminist vampire film, "Bit," the leader, Duke (Diana Hopper), delivers a speech to Laurel (Nicole Maines) about why being a vampire is better than the alternative for exactly that reason:

"The world's a meat grinder, kid. Especially if you're a woman. I don't think you need a PowerPoint presentation to know that one's true. We're politically, socially, and mythologically f—ed. Our roles are secondary. Our bodies suspect, alien, other. We're made to be monstrous, so let's be monsters. Let's be Gods. What we offer here is not a chance to join a group, but the chance to truly be an individual."

If you're someone who walks through the world without any real, tangible power, the chance to finally feel safe, strong, and in control as a vampire is an electrifying proposition. But the vampires in "Sinners" are not like the vampires in "Bit" or even "Fright Night." They have no intention of actually helping or building community with the Black attendees at the Juke Joint party, they want to infiltrate the group to steal their power and turn them into subservient followers in the process. They want to obliterate the Black joy, love, and resiliency found in the club, as evidenced by co-opting their musical prowess and convincing those they eventually turn into vampires to dance to their music instead.

White people often claim that assimilation is the key to liberation, telling marginalized people to act, look, and even believe the way they do in order to be "accepted" by society. But the truth is that these promises are nothing more than a tool of oppression. Assimilation cannot save us, and anyone who acts as if it can is a vampire looking to drain others of their individuality and yes, power. Vampire stories have always been about social issues, but Ryan Coogler beautifully subverts the modern pathway of telling these stories to remind the world of who the true monsters really are.

"Sinners" is now playing in theaters everywhere.