Why Dustin Hoffman Sued Warner Bros. For $66 Million Over An Agatha Christie Movie

As Hollywood hurtled toward the 1970s, the American film industry was in the midst of a revolution. The old studio moguls, who'd been flailing throughout the '60s to slake Baby Boomer audiences' thirst for movies that spoke to their generation, were being replaced by younger executives who understood the future of their business hinged on being able to palpably connect with this massive cohort.

As envelope-shredding movies like "Easy Rider," "Rosemary's Baby" and "The Graduate" became runaway blockbusters, the era's biggest directors and stars spied an opportunity to obtain greater creative and financial control of their movies. Since even the young execs were scrambling to figure out why Boomers flocked to an adaptation of a publishing sensation like "Love Story," but avoided, say, the film of John Updike's bestseller "Rabbit, Run," striking deals with artists who seemed to have their finger on the pulse of this generation, or whose name on the marquee all but guaranteed a decent return on the studio's investment, was crucial.

Ultra-powerful talent agent Freddie Fields understood that he had the town over a barrel, so, in 1969, he partnered with three of the top-earning stars in movies — Paul Newman, Barbra Streisand and Sidney Poitier — to form First Agents. The production company offered studios what seemed like a fair trade-off: the stars would take lower salaries in exchange for greater creative control of their films and a share of the profits. Steve McQueen joined this group in 1970, while Dustin Hoffman climbed aboard two years later. First Artists knocked out some big hits early in its existence (McQueen in Sam Peckinpah's "The Getaway," Newman in John Huston's "The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean," and Streisand in Irvin Kershner's "Up the Sandbox"), but struggled as the decade wore on.

First Artists would eventually be bought by Warner Bros. in 1980, but it really died a year earlier when Hoffman, irate over losing final cut on two films (one of which speculated on the details of Agatha Christie's mysterious disappearance in 1926), filed a $65 million lawsuit against his own company, his agent Jarvis Astaire, and Warner Bros.

Hoffman got nothing but grief from Agatha

While Hoffman joined First Artists in 1972, he wouldn't endeavor to make a project through the company until he acquired the rights to Edward Bunker's novel "No Beast So Fierce" as a project for him to star in and direct. Though the resulting movie, "Straight Time," is now correctly viewed as one of the actor's finest films, its production was difficult. When Hoffman failed to shoot a single frame of film after his first day on the job, he ceded the director's chair to Ulu Grosbard. Their improvisatory collaboration bore strange and wonderful fruit, but principal photography ran 23 days over schedule.

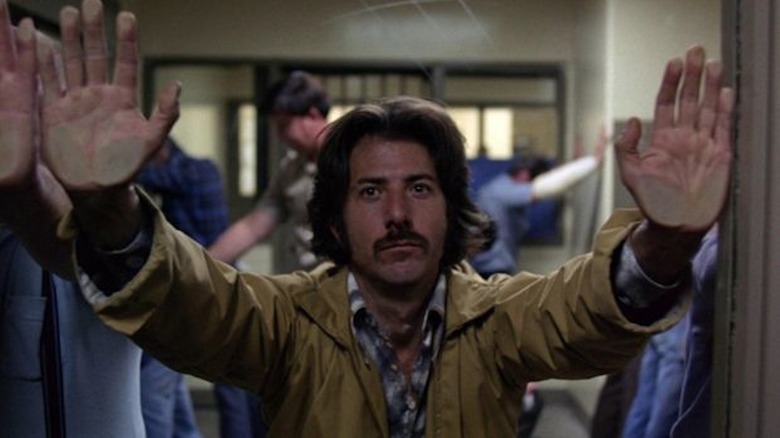

At this point, First Artists claimed Hoffman had forfeited his right to final cut, but, according to the actor, he didn't know the film had been taken away from him until he was shooting "Agatha," his second project for the company. While on Christmas break from filming "Agatha" in London, Hoffman hightailed it back to Los Angeles for a round-the-clock editing session on "Straight Time." He only had 20 minutes cut to his specifications before he was forced to return to England.

Hoffman was unhappy with "Agatha" before cameras rolled. Initially, his character, an American journalist who tails the author during her disappearance (motivated by her anguish upon discovering her husband is having an affair) was supposed to be a supporting part. First Artists allegedly insisted that the role be expanded to satisfy Hoffman's contract, which required a good deal of rewriting. When Hoffman and co-star Vanessa Redgrave realized the script was far from finished, they asked for shooting to be delayed several weeks so they could tighten the screws. When they were denied, Hoffman groused to the press.

Hoffman's legal fury was met with a countersuit

In a 1979 interview with The New York Times, Hoffman is described as being "close to tears" as he sifts through the wreckage of his First Artists productions. "Straight Time" clearly stings the most, and if you've ever seen the film you know why. He is brilliant as an ex-con who can't shake his old criminal reflexes. Ever the burrower, this is one of those bravura Hoffman performances where he disappears without making a show of it (as he did in "Papillon," "Lenny" and "Rain Man" – "Tootsie," yes, but making a show of it was the point of the performance). "You put in a lifetime of work and training and someone takes your paint brush away," he lamented to the Times.

He's fine in "Agatha," but aside from acting opposite one of the greatest actors of the 20th century in Redgrave, I fail to see what the appeal was for Hoffman (First Artists accused him of making the film in bad faith to satisfy his contractual obligation to the company). Still, he put in the work to rewrite "Agatha" per First Artists' specifications (alongside a team of writers), so it's understandable that he'd bristle over being rushed into production. "Once you go on that floor to make a movie, it's crazy time," he told the Times. "It's painting a picture on railroad tracks with the train getting closer. 'Agatha' was every actor's nightmare. The script was literally being rewritten every day. It was a rainbow of green, yellow, pink revision pages."

Hoffman's $65 million lawsuit against First Artists, WB, and Astaire was really about "Straight Time," which was seized from him when he was back on the set of "Agatha" after that Christmas break. "[T]hey waited until they had what they felt they needed on 'Agatha' before they took 'Straight Time' away," said Hoffman. First Artists filed a countersuit against Hoffman, alleging he'd harmed "Straight Time" commercially by publicly declaring that it was a compromised work. Over 40 years later, the result of this litigation is unknown. I do know, however, that Hoffman has made his peace with "Straight Time." When I interviewed him in 2008, he told me, "I like that movie. It's a true movie. It's as close to the reality of criminals that I'm aware of. Ex-convicts have said that that movie really gets it." I believe Hoffman, but the cynic in me can't help but wonder if an undisclosed 11-figure settlement helped to ease his prior anguish.