How Columbo's Mysterious First Name Spurred A $300 Million Lawsuit

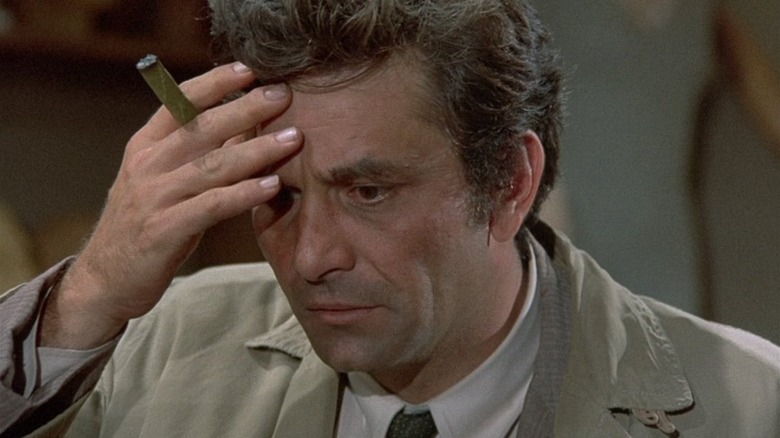

Lieutenant Columbo (Peter Falk) had many mysteries throughout his long-running TV series. For one, he made frequent allusions to "The Missus," his wife, an off-screen character whom the detective claimed to make certain demands of him as a husband. He never referred to his wife by her name, though, and he didn't wear a wedding ring. This led some "Columbo" fans to assume that she was a fabrication that Columbo had invented to appear more personable. The assumption, however, was laid to rest when other characters reported talking to Mrs. Columbo. She was real. Indeed, Kate Mulgrew played Mrs. Columbo in a short-lived spinoff series called "Mrs. Columbo." That series, however, tried to cut its ties with "Columbo," leaving its canon status in doubt.

Another one of Columbo's mysteries was his first name. He only ever introduced himself by his last name as, as a cop, so did everyone else. There were a few instances wherein Columbo flashed his badge and Police I.D. card (notably in the episode "Dead Weight"), but television sets in the 1970s were sharp enough to reveal what his vitals actually were. It wouldn't be until the show was digitally remastered for DVD that viewers would be able to make out the name on Columbo's I.D. card, learning that he was christened Frank.

There may, however, be some readers who have, for many years, been operating under the misapprehension that Columbo's first name is Phillip. You might have learned the name from the board game "Trivial Pursuit," which published the name in their 1983 Genus Edition. Most households had a copy of "Trivial Pursuit" in the mid-'80s, so the "fact" was widely spread.

It seems, though, that the makers of "Trivial Pursuit" stole the name "Phillip" from a trivia book called simply "The Trivia Encyclopedia" by Fred L. Worth. Worth, as it turns out, planted a few pieces of fake trivia he invented himself as a way of tracking down naughty board game publishers who might steal his work without permission. Worth took the matter to court.

Fred L. Worth planetd fake trivia in a trivia book, knowing that other trivia authors might steal it

The story of Fred L. Worth's clever anti-plagiarism tactics is related on the Trivia Hall of Fame website. Worth, the website explains, worked as an air traffic controller but was also known for his penchant for facts and trivia. In 1977, he published his well-researched tome "The Trivia Encyclopedia," which was an exhaustive collection of fascinating details about every possible subject. Two years later, Worth expanded the book, retitling it "The Complete Unabridged Super Trivia Encyclopedia," and it became a huge hit. Many households in the 1980s had a copy, as it served as the ultimate bathroom reader.

Worth, however, knew about the history of mapmaking and about how ancient cartographers would often see their work being openly plagiarized by publishers. Back in the day, said mapmakers would often deliberately include errors in their maps, letting them know when someone else was just copying things over and not doing their own research. The writers of trivia had similar problems, with some publishers copying over an author's research without giving them credit. Worth, to put a conceptual "watermark" on his book, wrote in several pieces of fake trivia. If someone copied a fake fact, he would know that he was being ripped off. One of the fake facts is that Columbo's first name was Phillip. It's a fun and clever way to assure the veracity of one's work.

"Trivial Pursuit," the Hall of Fame website says, was a massive success, making over $256 million in sales in the first months of its publication. When Worth came upon a trivia card in an edition of "Trivial Pursuit" — in the "Entertainment" category — saying that Columbo's first name was Phillip, he knew he had a smoking gun.

Fred L. Worth sued Trivial Pursuir for $300 million

Worth immediately took "Trivial Pursuit" to court, claiming $300 million in damages. In Worth's mind, it was clear that his book had been used as a resource and that he was never contacted or compensated for it. He sued John and Chris Haney, Ed Werner, and Scott Abbott, the creators of the game, as well as its distributor, Selchow & Righter (Hasbro owns the game in the 2020s).

Frustratingly, the case was almost instantly thrown out. Worth even got to hear, in court, that the makers of "Trivial Pursuit" did indeed use his book as a research tool, and they did indeed deliberately fail to credit him as a researcher. They also claimed, however, that they similarly ripped off hundreds of other sources in such a way. And, as we all know, when you rip off hundreds of different sources, it's usually just called "research" and not "plagiarism." Facts, after all, are not copyrightable. Worth's legal legs fell out from under him, and he was never credited or compensated, despite proof and a confession. Worth tried to appeal to the Supreme Court, but it wasn't taken up.

Weirdly, the fake "Phillip Columbo" fact continued to proliferate, and certain sourcebooks — like Jeff Smith's 1995 "The Guinness Television Encyclopedia" — continued to declare Columbo's name to be "Phillip." Of course, now you, dear reader, can smile anytime you see an ad or an article that declares Columbo's first name is Phillip. You will know that it was a fabrication by Fred L. Worth. One can now watch "Columbo" whenever they want.