Why Do So Many Modern Film Scores Sound Like '80s Music? The Movie Music Investigation You Need

Can a certain sound, made by a particular instrument, sum up an entire era?

It seems unlikely, yet think about those opening notes of Harold Faltermeyer's "Axel F" from "Beverly Hills Cop" or Brad Fidel's theme for "The Terminator," and you're instantly transported back to the 1980s. Of course, electronic music existed long before that decade. Yet the synthesizer-as-primary-instrument score came to prominence during the '80s, in part due to changing tastes in music and culture, and in part due to the steady rise of independent films, who needed to save a few bucks by employing just one musician instead of dozens.

While the popularity of the synth-heavy score during the 1980s is easily understood, what's surprising and less clear is why this type of sound has lasted ever since, and why it's still so prevalent today. Sure, '80s nostalgia began early and has never really left our culture since. Yet the synth-heavy score isn't reserved solely for nostalgic purposes, especially as that sound has mutated and combined with the rise of Electronic Dance Music (EDM) and electronica in general. The continued interest in using increasingly sophisticated technology to compose and perform original music has seen the '80s score sound evolve into a genre dubbed "synthwave," and that movement has inspired filmmakers to adopt the sound for movies which only seek to reference the '80s obliquely, films like David Robert Mitchell's "It Follows" and Adam Wingard's "The Guest." While this sound continues to crop up in movies made today, the '80s electronic score has also found its way to television, too.

Like any aspect of music (or art in general), the evolution of the medium is on a spectrum, and every new innovation ends up becoming subsumed into a melange of styles and influences that then breed further innovations. Yet the '80s-coded electronic style remains in our present-day soundscape, and it's worth investigating just how and why that came to be.

I spoke to four musicians currently working in the film and television industry, all of whom are composing scores that utilize this particular sound. During the course of our discussions, I was able to discover some potential answers as to the lasting power of the retro synth sound, and they seem to promise it isn't going to disappear anytime soon.

The seemingly evergreen lure of '80s nostalgia

The lingering prevalence of the 1980s isn't the usual form of cultural influence. There's a blatant continued existence of so much intellectual property of that era, including "Transformers," "Ghostbusters," "Beetlejuice," and numerous other examples. While those franchises and others have generally always been beloved, there are other aspects of the decade which were discarded soon after it ended. For a while, it seemed like the signature '80s synthesizer sound was also out of vogue, both in popular music and in film scores.

Sunglasses Kid, a British music producer, electronic musician, and composer who's contributed to the scores of "Cobra Kai" season 6 and "Beverly Hills Cop: Axel F," remembers a time when an '80s sound was anathema. "The moment that we went into the '90s, there was a lot of, 'Oh, '80s is bad.' I remember when I first started producing music, people told me that my music sounded a bit '80s, and I took that as an insult [...] '80s used to be like kind of a bad word [...] It was code for cheesy, or embarrassing."

Still, the popularity of '80s media and its aesthetics have never really gone away, which is not all that surprising given how the pop culture of a generation's youth tends to inspire a resurgence when those folks grow up and become the dominant artists. As Sunglasses Kid explains: "Those 30- and 40-year-olds have all moved into positions of being the creators and the creative decision-makers. So they start commissioning and controlling those movies, or whatever those art forms are. And then there's a market of people also nostalgic for it." He does point out that we seem to be in a particularly long cycle of '80s appreciation, however: "I was really surprised that people are still interested in [the '80s]. Because I was like, why hasn't this died yet and been replaced by the '90s? Why isn't the '90s [nostalgia] quite going as fully big as the '80s has done in pop culture?"

He does have a more concrete answer for why the '80s sound continues to be popular today, and it has to do with the way it combined new possibilities with limitations. "It was this real explosion of never-before-heard sounds. So there's suddenly this whole new exotic palette. And [today] we've got to this stage where, with computers, you could literally create anything. So there's a nostalgia for this time [where there was] a restricted palette of exotic sounds. Now, there's so much choice."

Thanks to the resurgence of the '80s sound, Sunglasses Kid observes that what used to be looked down on is now increasingly appreciated and accepted. "I think, the further and further we get away from the '80s, people like me are almost giving people permission to go, 'Do you know what? That was actually awesome.' And what may have, in hindsight, seemed cheesy or dramatic, now somehow seems actually kind of amazing."

Drive and the dawn of synthwave

Of course, '80s nostalgia couldn't have continued as much as it has without a little help from highly influential, milestone work. For Sunglasses Kid, that work was Nicolas Winding Refn's 2011 film "Drive," with its pulsing Cliff Martinez score, neon-and-street-lights visual palette, and its electronica needle drops, especially "Nightcall" by Kavinsky. "Kavinsky's 'Nightcall' is seen as the song that really started this new '80s sound. I definitely would say I've noticed '80s-sounding stuff being used before them. But Kavinsky's 'Nightcall' and that whole soundtrack for 'Drive' was what inspired me and a lot of people to start re-exploring that palette of sounds, and making stuff sound more '80s."

Zach Robinson, who, along with Leo Birenberg, has composed the score for "Cobra Kai" during its six-season run, similarly remembers "Drive" as a turning point, especially as he was already involved with retro music fandoms and musicians online when the film dropped. "I guess my freshman year was like 2008, 2009, and I started doing synthwave stuff, but it wasn't called synthwave [yet]. It was just '80s retro music and it was all on MySpace. My moniker was D/A/D. There was a huge MySpace community of '80s retro artists ... and it was pre-'Drive,' I like to say. There's a historical bifurcation."

Naturally, the genre that eventually came to be dubbed synthwave didn't emerge solely because of "Drive." As Robinson explained, this music genre was formed through prior genres of electronic music such as French Touch (consisting of groups like Justice and Daft Punk), leading to people like himself playing with synth sounds online that sought to be both pioneering and retro all at once. "[It was] just [about a] homegrown, 'person with a synthesizer in their room' vibe, who really tried to go more '80s than just a dance record. It was trying to bring that nostalgia of something that didn't quite exist in the way that we all remember it. And then there was 'Drive,' and then the post-'Drive' wave, which is third wave ... and then there's probably a new one now, which is more like a mainstream [wave]." This latest wave feels like the natural endpoint of any musical genre that's fully emerged, which is that it's continuing to mutate and expand thanks to the cross-pollination of the musicians themselves.

The more experimental side of retro sounds

Yet synthwave is only part of the story. Not only does synthwave have its own subgenres, like dreamwave and outrun (whose terms are sometimes used interchangeably with synthwave itself), it also stems more from a pop music space than from a film music space, essentially. That's an opinion certainly held by Kyle Dixon and Michael Stein, two members of the electronic music band S U R V I V E who exploded thanks to their work composing the score for the Netflix phenomenon "Stranger Things." Although that show unabashedly revels in evoking nostalgia for the 1980s, Dixon and Stein approached their work on it from a more experimental angle. Though S U R V I V E is typically categorized as a synthwave group, Dixon stated: "I think that synthwave was invented in 2016 by Lakeshore Records. That word, I never heard it until they decided to blast it all over the place." Stein summed up their view of synthwave as being something primarily aesthetic: "It feels sort of like it's nostalgically calling upon '80s music in a modern way of ... sort of the feeling it evoked. But it doesn't really actually sound very much like the music from the '70s and '80s that was synthesizer-based."

Instead, the duo find their influences and inspirations coming from other, more experimental corners of electronic music made during its early years. "I think a lot of our core influence comes from more of the earlier electronic records, like stuff from more of the '70s and '80s, which doesn't sound as much like what the contemporary version of synthwave is." Dixon recalled first hearing the Japanese band Yellow Magic Orchestra (YMO) as being more formative for him than any pop music from that period: "I think the first music that was from the '80s that I really liked [was] some YMO stuff — only a few songs, not all of them. But I was like, 'Oh, this sounds like they're doing really interesting stuff with the synthesizers.' And this is from 1983. That's crazy. In my brain I was like, 'They're doing Aphex Twin, but it's 1983.'" While this may sound slightly shocking coming from the composers for such a nakedly nostalgic series, one only needs to listen to their music (some of which was featured in "The Guest" as well) to hear its depth and uniqueness.

Finding the emotional ghosts inside the machines

Like any good composers, Dixon and Stein, Robinson, and Sunglasses Kid are ultimately all after the same thing, which is to best evoke the emotion of the story the film or series is trying to tell. For his part, Robinson talked about how the retro synth sounds can further help in this regard. "That's why I like doing film music," he said. "It's all emotion, it's all tone. Every time I listen to a piece of music, whether it's film music or not, I'm thinking of something in my head that the music is evoking, imagery. And I think that's why this type of music is actually so effective. There's a palpable sense of nostalgia that one gets, and it's made-up nostalgia. It's not like the '80s were a great time, necessarily. There was a lot of social upheaval in the world happening. But the people who [are] making this music, it's like they were kids or whatever, and I think there's a nostalgia for that. And there's so much imagery that comes to mind that's evocative from synthwave and from just '80s revival music. It's got such a specific sound and it's got — I mean, the rise of synthesizers, and the rise of just no-holds-barred, unabashed, gigantic production that doesn't exist in other decades. It's really such a unique sound."

On "Stranger Things," Dixon and Stein underlined how the Duffer Brothers and the other filmmakers involved give them room to find the proper emotions. "They've definitely given us a lot of freedom to try and do what we want," as Dixon said. As a result, the duo essentially have license to experiment with their music in order to try and obtain the right sound for the right moment. "We like to use a lot of hardware and synthesizers, which is no secret, but we try to do as much stuff on real things as we can, less in the computer ... We do try to do everything as much in the real domain as possible, which is not how most people make music now [...] You can easily make something that sounds like synthwave with just your laptop, but it's not going to sound the same. I really don't care what you use as long as it's interesting music. I'm not trying to be a snob about it, but I think just because we are doing things with some of the older [equipment], there's a lot more newer stuff, so there are less limitations now because everything is functioning together a lot better than when we started. When we started doing this, you had to go through a lot to just get modern functions out of some of this old stuff."

Stein added to Dixon's thoughts, underlining how their music is more about the work itself than trying to evoke anything in addition to it: "I think when we approach music with electronics, we tend to focus on the mood and the emotion and the sound design just as much [...] So we try to inject a lot of emotion rather than the nostalgic sound characteristic, if that makes sense. It's hard not to sound like you're using synthesizers when you're using all synthesizers."

Synth scores are no longer regarded as shortcuts, but a viable, affordable alternative to traditional scoring

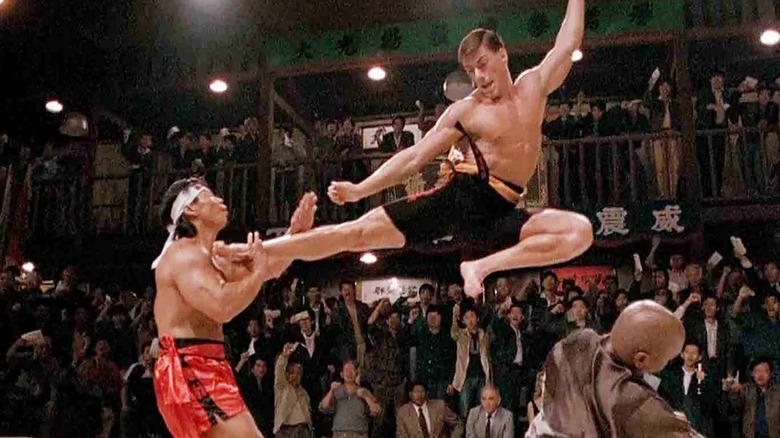

A large part of what has allowed the synth sounds of today to flourish is that, given our hyper-digital age, the idea of creating music using electronics as a tool is no longer stigmatized. As Robinson explained, there was a time in the mid-'80s where paying one musician to create an entire score versus a traditional studio orchestra looked like a money-saving measure: "There's not an immediate reaction to, 'Oh, I hear a synth and it's cheap' anymore. That was a signifier that you had a cheap movie [...] a B-movie [score] from the '70s was just three synthesizers or whatever, or [something like] Paul Hertzog's 'Bloodsport' score [was seen as] cheap, because it's just a guy in a room. Now, a guy in a room is really cool."

Robinson points out that, these days, it's more about a production properly budgeting for the kind of score they want to have. "I think most of the time, most people don't know what anything costs. So, I don't know how much that is a conscious effort to cut down on budget. You need a real orchestra to sound like a Hollywood movie, but I think that the bigger issue is that TV scores, which [have] a smaller budget than film, now audiences expect to hear movie scores for TV, and budgets don't reflect that [...] On 'Cobra Kai,' we record everything. We're one of the few [...] but that's because they put a premium on the music [...] A lot of [other shows are] done overseas. Most stuff is done overseas, because it's cheaper [...] Synth scores definitely exist because they are cheaper, for sure." Dixon seems to agree, summing up the notion succinctly: "It's a lot cheaper to buy a few synthesizers or just use some software than to hire a hundred people to play something or even rent out a studio."

Electronic sounds have become a permanent part of today's musical landscape

So, why has the '80s electronic sound continued to exist today, whether in an intentionally retro mode or in a newly mutated form? The answers vary, of course, but according to Robinson, it's all about the sound being a choice rather than something trendy or easy. "A guy with a giant synth track is really cool — or girl — and it's just different. Now, I think it's taste. I think the score to 'Challengers' is a great example of just Luca Guadagnino just [being] like, 'I want a Nine Inch Nails album for a score,' and that's cool."

As Stein accurately observes, the synthesizer has become such a permanent color in the palette of film scoring that it turns up in most modern film scores today, leaving more traditional orchestra-based scores feeling more retro than synth ones. "Even all the big Hollywood orchestral scores, they're using synths for sub-bass and they're using synth for effect and it's not common that there's no synth because if you're building a world — and scoring is building a world of sound that fits the picture or the place — the synthesizers and electronics and plugins will give you so much control over sound design that if you're trying to create something unique, you're going to have more access to [...] how creative you can be with a Western orchestra. Some people can do very interesting arrangements and voicings to create very unique spaces and sounds. Even the '80s, a lot of the '80s music scores were orchestral, and people tend to not talk about how much [the scores of] John Williams or Alan Silvestri, which had no synthesizer in them, [how] if you do that exact thing now, that sounds more dated, I think, than doing synthesizer music, unless you're really trying to do retro callback music."

Dixon took that observation one step further, remarking how the synth sound has become dominant in popular culture. "The sound of a synthesizer is more current now than [ever]. Most people are not ever going to hear an orchestra. It's not on the radio ... they're not even going to accidentally hear it because there is no radio. They're just playing whatever they search for on their phones, and I'm using pop music as an example, but that's all synthesizers [...] So you've got this digital electronic music that is just more common than orchestras."

The sound of the '80s will never die

In addition to all of this, there remains some magical, inexplicable nostalgic pull to the sound and the era that has yet to be severed. As Robinson wondered aloud: "Why has this survived? Why is this still around, other than the obvious answer of like, 'Oh, it's nostalgia, blah, blah, blah,' but I just think it's cool that things can have a legacy this long and still be relevant to people, like the Y2Kers and younger, who [are] babies, and they're born suddenly being like, 'I want to listen to Tangerine Dream.'" This yearning by people who weren't even alive during the '80s to participate in it is something Sunglasses Kid sees regularly. "I get people who are in their twenties, in the comments and things, saying, 'Damn, why am I nostalgic for this time that I wasn't even alive in?' Or 'I feel like I wish I had been there.' There's a sense of something."

Ultimately, it's one of the tenets of art for certain techniques to be so successful that they stick around, as Sunglasses Kid says: "It's like imagining in the 1980s they suddenly discovered a whole new range of colors of paints, and then going, 'Do you ever think these new colors will ever go out [of] fashion?' And maybe the different styles of painting will evolve, and what's in and out, in terms of realistic or impressionistic. I think that will continue to change. But I think this palette of colors will continue to be around."

The future is unknown; we will undoubtedly find new sounds, and it's certainly possible that '80s nostalgia will eventually burn out. Yet the synth sound of the '80s will continue to resonate, its electronic nature a continually compelling fusion of past and future, so much so that it escapes its nostalgic origins and becomes timeless.