10 Best Episodes Of The Sopranos, Ranked

Some of the greatest stories ever told were told on "The Sopranos."

For six seasons, HBO broadcast the lives and deaths of the titular New Jersey family, led by mob boss Tony Soprano (James Gandolfini), his conflicted and complicit wife Carmela (Edie Falco), his aimless, hot-headed nephew Christopher (Michael Imperioli), and his scheming uncle Junior (Dominic Chianese). While other crime shows portrayed criminals like these as cowboys conquering the new American frontier, series creator David Chase imagined them as tragic antiheroes, clinging to a fading world as the mundane and universal realities of life knocked them off their horses and into jail cells, nursing homes, and early graves.

Chase and co. made their series even more striking by having "The Sopranos" eschew serial-storytelling conventions of constantly progressing overarching plots and regular cliffhangers, instead approaching each episode as though it were a standalone story. The result was not only a monumental TV epic but 86 individually moving stories that could take viewers on a journey in the same way a short film would — some of them even more so. These are the 10 best episodes of "The Sopranos," ranked.

10. Commendatori (Season 2, Episode 4)

"Gotta hand it to ya, great fruit you got here... 'Kay bell-ay fruit-ay!"

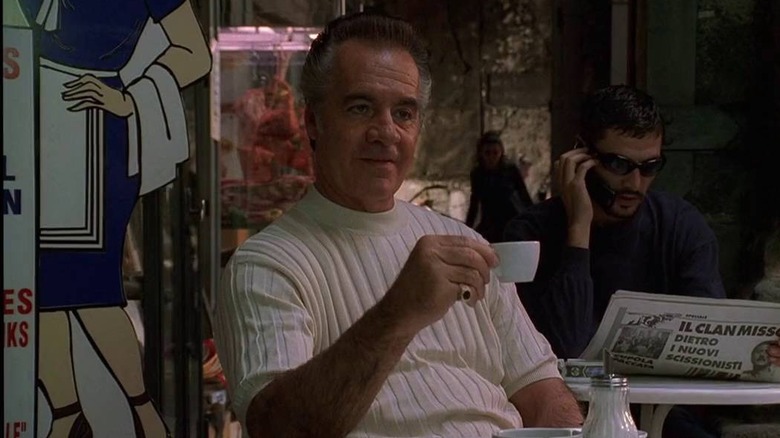

"Commendatori" is, in many ways, a quintessential episode of "The Sopranos." In it, Tony travels to Naples, Italy with Christopher and Paulie "Walnuts" Gaultieri (Tony Sirico) to negotiate an illicit business deal with their Italian counterparts in the Camorra.

The episode possesses all the variously disparate qualities that made the show a masterpiece — gorgeous and occasionally grand cinematography; a poignant use of comedy to underscore social commentary (the hard-cut away from the opening car-jacking sequence is a high point of the series in this regard); the deconstructing of Mafia mythos and mob-movie tropes; equally entertaining subplots in the form of Paulie's hilariously shallow attempts to reconnect with his heritage, Carmela processing her growing dissatisfaction with her marriage through the negative experiences of her fellow mob-wives, and the escalating danger of Pussy Bonpensiero's (Vincent Pastore) collaboration with the FBI. It even manages to fit in one of the show's famously interpretive dream sequences and introduces the character Furio Giunta (Federico Castelluccio).

Perhaps the most compelling aspect of "Commendatori" on a rewatch is how deftly it paints the characters' struggle for cultural identity, as well as how they react to their failure to fit in with either the impenetrable culture of "the old country" or the "medigans" they terrorize back home. Just as the non-Italian-American family from the aforementioned car-jacking scene is abandoned by the dog they curiously named after British P.M. Winston Churchill, "Commendatori" reveals just how distant and oblivious Tony and his ilk are to the culture they supposedly champion. As the series continues to use the decline of the Mafia as a metaphor for the cultural evolution of America, "Commendatori" stands out as a flashpoint in this journey.

9. Cold Stones (Season 6, Episode 11)

"I don't understand... Dad wasn't a spy?"

The way in which "The Sopranos" explores the sexuality of Vito Spatafore (Joseph R. Gannascoli) remains one of the most surprising things about the series as a whole. Though it had been hinted at and rarely depicted explicitly throughout the latter half of the series, dedicating a multi-episode arc to his escape and fateful return to New Jersey during the final season was a risky move — one that ultimately yielded some of the series' most haunting and powerful moments. It was difficult for us to choose between these episodes — the tense succession of revelations in "Live Free or Die;" the unexpected but touching romance of "Johnny Cakes;" the tragic constraints of Vito's true nature, conveyed with banal cruelty in "Moe n' Joe." But it's "Cold Stones" — the episode in which Vito attempts to return to his life of crime and is swiftly punished for it — that deserves the spot on this list.

The description of his death at the hands of Phil Leotardo (Frank Vincent) is horrific enough, but the performances from both Gannascoli and Vincent in the scene leading up to it are what stick with us. Vincent in particular leaves viewers with more questions than answers, as his eerie gripping of the bed sheets as Vito is violently beaten indicates a range of complex emotions. "Cold Stones" is a rough and perhaps even distressing watch to this day. But for a show as grim as "The Sopranos," it was a perfect end to Vito's storyline.

8. Whoever Did This (Season 4, Episode 9)

"What sick f*** would do something like that on purpose, huh?"

By the end of season 4, Ralph Cifaretto (Joe Pantoliano) had spent two seasons making a solid case for himself as the most vile character in an ensemble of liars and murderers. His sadistic behavior (exemplified by the cruel and brutal slaying of Tracee, a Bada Bing dancer he believed to be pregnant with his child) was made all the more unsettling by how easy it was for him to lie and/or buy his way into the good graces of the right people to avoid accountability. However, in "Whoever Did This," "The Sopranos" finds a satisfyingly indirect way to finally punish Ralph for his sins.

The episode is best summed up by its non-committal title, both a nod to Ralph's slippery nature and, arguably, a refusal from the writers to reveal the culprit behind the episode's central mystery — whether or not Ralph set fire to the barn that housed his and Tony's prized racing horse to secure a $200,000 insurance payout. This tragedy comes after Ralph's son has been mortally wounded in an accident, inspiring two needs within Ralph — immediate cash for medical bills and spiritual redemption — that drive two opposing reads of the story.

In one, Ralph's flimsy attempts at redemption are subverted by his base impulses, leading him to kill Pie-O-My for an easy cash infusion. In the other, Ralph really didn't kill Pie-O-My, but he's unable to convince Tony of his innocence because of all the evil he'd gotten away with in the past. Without total accountability, Ralph is denied the clean slate he seeks through charity and renewed moral clarity. Tony's rage-filled admonishment of Ralph during his final moments is brilliantly written in such a way that it could apply to Pie-O-My or Tracee, and the audiences is left to wonder what Ralph is truly being punished for.

7. Soprano Home Movies (Season 6, Episode 13)

"You Sopranos... You go too far."

The best episodes of "The Sopranos" often feel like short films — self-contained stories that are emotionally satisfying and dramatically compelling on their own, without the need for prior context or explicit forward narrative momentum beyond the credits. In comparison, "Sopranos Home Movies," which possesses these qualities in addition to a unique but secluded location and a story with a narrower scope and smaller ensemble, feels like a stageplay.

The episode's beauty is in its simplicity. "The Sopranos" kicked off the second half of its two-part final season with Tony's birthday-trip to the lake with Carmela, his until-recently-estranged sister Janice (Aida Turturro), and his brother-in-law-slash-employee Bobby (Steve Schirripa). Like the rest of the season, the episode sees the don of New Jersey wrestling with his fate in the wake of his near-fatal shooting at the hands of a dementia-ridden Uncle Junior, leading to an unusually contemplative discussion between Bobby and Tony about the nature of death and, uncomfortably, the lives Tony has taken.

Tony describes murder as "the big fat pain in the balls." Bobby — who notably hasn't killed anyone yet — assumes he is talking about the "pain" of getting away with the crime, but James Gandolfini's delivery (and Tony's habit of dreaming about his victims) implies existential guilt. The fact that Tony then forces Bobby to carry this profound guilt as punishment for humiliating him in a drunken brawl is the best example of how devastating "The Sopranos" can be with even its smallest stories.

6. The Test Dream (Season 5, Episode 11)

"Why don't you tell them what happened 20 years ago?"

A huge part of what makes "The Sopranos" memorable over two decades after its premiere is how unafraid it was of getting weird. To stay grounded while doing so, the show always roots its idiosyncrasies within the complex psychology of its protagonist, as was often vividly depicted in surreal dream sequences. "The Test Dream" features the series' most ambitious dream yet, lasting half the episode and taking Tony on a journey to every corner of his subconscious.

Series creator and episode co-writer David Chase stakes his claim here as the king of the dream sequence trope. Not only does he smartly use it as a creative means of depicting how conflicted Tony is about killing Tony Blundetto (the cousin he abandoned 20 years prior, played by Steve Buscemi), but he takes the chance to explore the implications of Tony's vast mental landscape — from his treatment of women and his pathological obsession with JFK (represented by a baffling cameo from Lee Harvey Oswald) to his obvious guilt over the people he's killed and the lives he's ruined. The best part is that, in contrast to other TV dreams, this dream actually feels like a real dream both because of how bizarre and unexplainable it is at times and because it doesn't give Tony any clear answers. And yet it still succeeds as a story, because it clearly establishes the emotional stakes of Tony's journey going forward.

Also, Annette Bening is there.

5. College (Season 1, Episode 5)

"Did the Cusamano kids ever find $50,000 in krugerrandts and a .45 automatic while they were hunting for Easter eggs?"

The top-of-the-class when it comes to episodes that represent the short-film mentality of "The Sopranos," "College" could be shown to someone who's never seen a single shot of the series and turn them into a lifelong fan. It follows two nearly-equal storylines that examine the impact Tony's life has on his family. In the primary thread, Tony's daughter Meadow (Jamie-Lynn Sigler) confronts him about his position in the Mafia during her college road trip. Though his surface-level honesty initially brings them closer, he's quickly reminded of why he needs to keep her at arm's length when presented with an opportunity to kill a former family soldier who turned state's witness.

Meanwhile, at home, Carmela has an intimate dinner with Father Intintola (Paul Schulze), where boundaries are blurred and she eventually seeks absolution for how her complicity in Tony's crimes could impact her children. Though it feels intensely real in the moment, the cold light of morning paints their night together as spiritually empty, built not on salvation or even love but wine and ziti. By the time the story reunites Tony and Carmela, both have retreated further into corrosive, self-rationalizing moral pits they clearly want to escape. Now, they must do so with a new understanding of how their choices will shape the future of their family.

4. Long Term Parking (Season 5, Episode 12)

"That's the guy, Adriana. My uncle Tony. The guy I'm going to Hell for."

In contrast to "College," "Long Term Parking" is an episode of "The Sopranos" that works because of everything that came before and everything that comes after. After five seasons of heartbreak, abuse, and genuine moments of love, the series resolved Christopher and Adriana's (Drea de Matteo) relationship the only way it could — with Christopher ultimately choosing the family over the woman he supposedly loved, facilitating her execution for collaborating with the FBI.

There are plenty of impactful dramatic moments both big (Christopher making his decision after seeing a normal family loading into a car at a gas station) and small (him later dumping his suitcase in the same place he was almost executed himself by Tony) that make it one of the greatest climactic episodes in TV history. But it's the continued use of cars and vehicular imagery — appropriate for Christopher, who began as Tony's driver yet ironically felt like he was in the passenger's seat of his own life — that strikes us on a rewatch. Here, the title "Long Term Parking" could imply the end of Christopher's moral growth and the damning soul.

But the episode also sets up the symbolic use of cars to be made explicit in later episodes like "The Ride," in which Tony and Christopher speed away from a robbery only for it to yield shallow "remember when" conversations in the aftermath (no coincidence the episode also reveals that Christopher is to be a father and shows us for the first time the conversation he and Tony had when he learned Adriana was working with the FBI). This set-up from "Long Term Parking" is ultimately paid off in "Kennedy and Heidi," which sees Tony murder Christopher and tell the family he died in a car accident.

3. Whitecaps (Season 4, Episode 13)

"I know you better than anybody, Tony. Even your friends. Which is probably why you hate me."

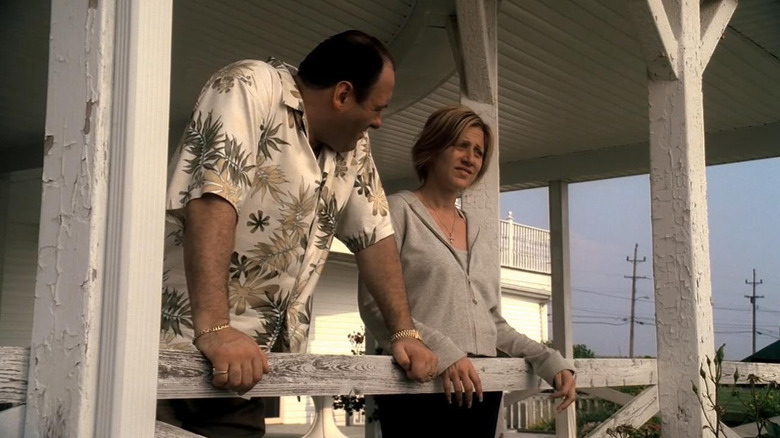

Alongside "Whoever Did This," much of season 4 of "The Sopranos" explores the relationship between redemption and accountability. Though the series' characters had always painted over their sordid lives with wealth, charity, and the aesthetics of family and tradition, they find the limit of this gloss by the end of the season. Just as Ralph is judged in his own fashion, Tony and Carmela are finally forced to reckon with their inhumane marriage after a grand romantic act that once might have redeemed it.

Though Tony purchases a beautiful shoreline house for Carmela to enjoy and for their children to one day inherit (a costly commitment to their future and a superficial answer to what Carmela had been asking for in the form of financial planning the entire season), Tony's rampant infidelity comes back to light and forces Carmela's hand. What follows his belongings flying out the window of their North Caldwell mini-mansion is one of the greatest TV scenes ever written or performed, with James Gandolfini and Edie Falco making a non-stop, blistering exchange of insults and repressed wounds feel nuanced and dramatically apocalyptic.

2. Made in America (Season 6, Episode 21)

"Isn't that what you said one time? Try to remember the times that were good?"

There's truly nothing we can say about "Made in America" that hasn't already been said, theorized about, or confirmed by David Chase, only for him to deliberately contradict it later. The infamous series finale of "The Sopranos" is a perfectly confounding end to a show that flaunted a distrust in closure, preferring to challenge its audience to continue wrestling with ideas after the credits rolled each week (a dramatic philosophy perhaps cheekily referenced in the show's final music cue, Journey's "Don't Stop Believin'").

Indeed, "Made in America" stands apart from other series finales for creating the feeling that things really could go on forever. Its breathtakingly patient, not only in its pacing but with the characters and moments it chooses to give attention — another series might struggle to justify a sudden interest in the family of Patsy Parisi (Dan Grimaldi) or the romantic life of FBI Agent Harris (Matt Servitto) in its final hour, and yet it serves the series' defiant forward-facing attitude that oscillates between pessimism and optimism scene to scene.

The wider focus also serves to shrink Tony and his world in a tragic but fitting way. Outside of the TV show, Tony is not the center of the universe, and he matters no more or less than the Bada Bing dancers the camera inexplicably lingers on as he considers his declining legal prospects. Whether or not he dies, the world will move on, and everyone featured in the diner will live the kinds of full lives his sociopathy prevents him from understanding beyond detached snapshots.

Tony could have gone out with a self-destructive final mission that encapsulates his capacity for violence and emotion, just as his dramatic descendent Walter White did. But despite the erroneous comparisons with "Breaking Bad," no TV series has recaptured the energy "The Sopranos" did — "Made in America" is just one example of why.

1. Pine Barrens (Season 3, Episode 11)

"Captain or no captain, right now, we're just two a**holes lost in the woods."

The most perfect episode in a perfect season of television, "Pine Barrens" remains the gold standard of "The Sopranos." Every other episode on this list gets a great deal of (hard-earned and well-deserved) mileage out of the vital ornaments of storytelling — theme, symbolism, character development, dramatic resolution, etc. "Pine Barrens" excels on sheer storytelling skill, taking viewers on a journey that's too exciting and, oddly, hilarious to be topped by arguably any other episode of TV.

The central plot of the episode explores the relationship between Christopher — a newly made man with growing, valid concerns about the chaotic and self-interested way their family is run — and Paulie, the physical manifestation of these concerns. This is made evident when Paulie turns a simple collection run into a body-dumping operation after he seemingly beats a Russian commando (Vitali Baganov) to death over a petty dispute. The two men's joint incompetence (and the Russian's unexpected survival) ultimately leaves them stranded in a frozen forest for a day, creating a tense hour of storytelling that forces both characters to the edges of sanity and morality. In the end, however, Christopher backs Paulie, and their survival of the ordeal seems to have bonded them closer together — perhaps a loose metaphor for how the family operates as a whole, essentially solidifying Christopher as a true, worthy member.

"Pine Barrens" is a reminder that while "The Sopranos" regularly succeeded at delivering genuinely insightful social commentary, shocking twists, comedy, and thrills, it never needed them as crutches. They were always tools judiciously employed to tell satisfying one-hour stories week-to-week. Given that most modern TV shows fail to grasp this as a basic concept, it's no wonder "The Sopranos" still reigns as one of if not the greatest TV show ever made.