10 Best Anti-War Movies That Will Leave You Thinking

The question of whether it's actually possible to make a true anti-war film has, without hyperbole, hovered over the entire history of film, without ever quite being answered to satisfaction. What makes it a tricky imbroglio is that the very idea of anti-war filmmaking presupposes that a film will be going against one of the core tenets of commercial cinema: The mission to thrill, entertain, and satisfy viewers. To be truly anti-war, a movie can't stop at just paying lip service to the idea that war is a bad thing whose professed heroics are an illusion; it has to actually live that idea, inhabit it in its very emotional charge, making an active effort to not glorify combat or naturalize war's dehumanizing emotional logic by wringing catharsis from its trials and triumphs. And, by nature, any such movie will be some degree of unsatisfying, if not outright hostile to the viewer.

This also applies to the 10 movies listed below. Two of them are dark comedies, seven are excruciating dramas, and one is an unclassifiable third thing, but none of them are remotely giddy or cathartic or heartening to watch — except by the implication that humanism, solidarity, and critical thought persist through them, even in the most jingoistic of times. Steel yourself to be completely denied any dishonest alleviation or release, prepare to feel incredibly angry and emotionally worn out, space out your viewings accordingly (or not, if you want to dive all the way into sorrow while you're at it), and good luck.

The Ascent

Considered by many critics to be one of the best war films of all time, Larisa Shepitko's "The Ascent" is an anti-war statement that veers from the moral and political into the metaphysical. Shepitko's command of imagery, editing, and the basic grammar of bodies cast against vast landscapes is nonpareil in the history of black-and-white film, and what she does in "The Ascent" is harness the spiritual charge of that imagery to reflect on the very nature of spirituality, and on the way the extremities of war at once brutalize it and bring it out.

Released in 1977, the film follows two Soviet partisans at the height of World War II who detach from their unit to go search for food in a Belarusian village. Ultimately, they are forced to make their way into enemy territory and soon find themselves embroiled in a life-or-death conflict with German soldiers. As they fight for their survival, Sotnikov (Boris Plotnikov) and Rybak (Vladimir Gostyukhin) are forced to reckon with the darkest recesses of human nature — in their enemies as well as in themselves.

It's one of the saddest movies of all time, as well as one of the headiest: A meditation on the devastation of war that goes beyond dwelling on the violence and the amorality per se, and ponders the corrosive effect that war has on the human soul, and on humans' relationship to the world. Shepitko was a poet of light, and "The Ascent" is her most aching requiem.

Come and See

Larisa Shepitko's husband, Elem Klimov, was also a film director, and his masterpiece, 1985's "Come and See," is considered by some to be the definitive statement against war in film history. At the very least, it's probably the most harrowing and most persuasive anti-war movie: Possessing the relentless intensity and stultifying brutality of a horror movie even as it limits itself almost entirely to realistic incident depicted without any trace of sensationalism, "Come and See" is the kind of great movie that's all but impossible to bring oneself to watch more than once.

What makes "Come and See" so gut-wrenching, in addition to Klimov's expertise in springing for tragic poetry and existential terror with his images and editing choices, is the fact that it unfolds from the perspective of a child. Flyora (Aleksei Kravchenko) is a Belarusian teen who gets conscripted into the Soviet partisan forces during the Nazi occupation of Belarus, hoping to aid in the war effort against the German invaders. He meets a teenage partisan nurse named Glasha (Olga Mironova), and, before they've even had time to take stock of their condition, the two kids get pulled into a maelstrom of death, violence, and chaos from which they find themselves unable to escape.

Klimov charts the sheer, mind-numbing surreality of wartime more adroitly than virtually any other director ever has, vaporizing any illusions that would hold it to be anything other than an abject hell. There must have been something in the water in the Klimov-Shepitko household.

All Quiet on the Western Front (1930)

With all respect to Edward Berger's multi-Oscar-winning 2022 effort, sometimes there's just no beating the original. The first adaptation of Erich Maria Remarque's "All Quiet on the Western Front," produced by Universal Studios and directed by Lewis Milestone, was released just one year after the novel's publication in 1929 and has yet to be topped by either of the two subsequent new takes.

It's not because of the Hollywood lavishness of the 1930 production, though there's plenty of that; this was by far the most massive and technically proficient war-themed sound film produced in the United States up to that point. What makes Milestone's "All Quiet" an enduring masterpiece is what it doesn't have in common with typical Hollywood fare — namely, a direct, eloquent, unsparing moral and political point of view.

Following a group of German boys on the brink of adulthood as they're persuaded into enlisting in the army during the early days of World War I, the film charts the teens' rude awakening with a sober, almost nonchalant attitude, matter-of-factly presenting the human horrors and political atrocities that befall them in relentless succession. All the while, the characters openly voice their changes in perspective brought on by war, never once refraining from expressing the ruination it has wreaked in their souls. It's arguably the defining cultural relic of the interwar period — a film made during a brief window in which "war is bad" almost seemed like a universally agreed-upon sentiment.

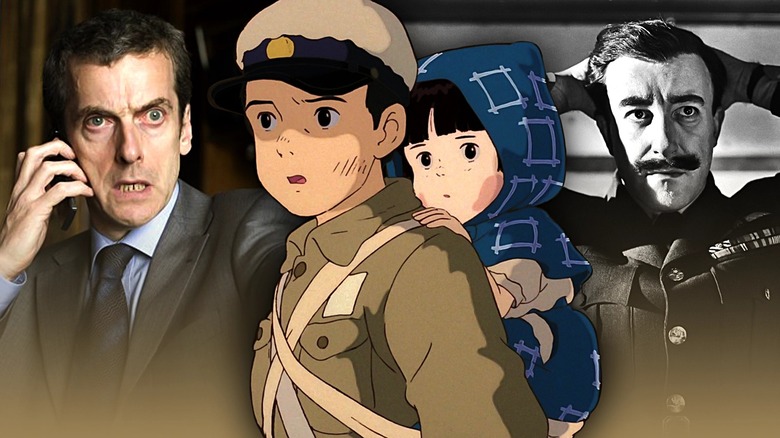

Grave of the Fireflies

There have been numerous great anti-war animated films, including the likes of "Barefoot Gen," "When the Wind Blows," "The Breadwinner," and "The Wind Rises." However, the definitive film to utilize the medium of animation in service of a lament against the inhumanity of war is still Isao Takahata's "Grave of the Fireflies." This 1988 classic is widely considered one of the best Studio Ghibli movies for good reason: It's a dark, forthright, emotionally crushing descent into the most unbearable depths of its subject matter, willing to burrow deep into places most animated films wouldn't dare even glance at.

Takahata's film follows young siblings Seita (Tsutomu Tatsumi) and Setsuko Yokokawa (Ayano Shiraishi), the children of an Imperial Japanese Navy captain, through the final days of World War II's Pacific Theater. The siblings lose their mother (Yoshiko Shinohara) during the United States' bombing of Kobe and are forced to fend for themselves amidst the devastation of the city. Although their youthful perspective — especially that of the pint-sized Setsuko — does ensure that the Yokokawas manage to find moments of levity and fun in between the long stretches of penury and suffering, the movie does not shy away from the reality of their circumstances: The hunger, the bitterness, the constant grief, the inability to handle things. Takahata duly depicts them as kids out of their depth, which only makes it all the more heartrending to see them have horror, pain, and injustice repeatedly foisted upon them by a supposedly functional adult world.

The Human Condition

It's impossible for an anti-war film worth its salt to even attempt to be apolitical, and few directors in history have understood that as acutely as Masaki Kobayashi. The Japanese New Wave legend behind such widely-known genre classics as "Harakiri" and "Kwaidan" (the latter one of the best ghost movies of all time), Kobayashi could direct supernatural horror and samurai action like nobody's business, but he made a series of historical dramas his arguable magnum opus with "The Human Condition" trilogy.

The three films — in order, 1959's "No Greater Love," 1959's "The Road to Eternity," and 1961's "A Soldier's Prayer" — are really just chapters in a single massive nine-hour epic, which charts the various twists and turns in the life of Kaji (Tatsuya Nakadai). A pacifist and socialist, Kaji accepts work as a labor chief in Japan-occupied Manchuria to avoid being drafted into the imperial war effort. But his attempts to adhere to morality and humanity in his post prove fruitless, and he ultimately gets thrust into a taxing journey through the grotesqueries and indignities of Imperial Japan's brutal warmongering culture.

The film was largely inspired by Kobayashi's own experiences as a pacifist and socialist drafted into the belly of the beast during World War II, and represented a major turning point for Japanese cinema: Rarely before had the country's films criticized the war effort so openly and pointedly, let alone with such passion and artistic mastery. "The Human Condition" is a work of cinema that buzzes with the urgency of an aggrieved man exorcising his own past.

Europa, Europa

There had been plenty of Holocaust-themed films by the time Agnieszka Holland made "Europa, Europa," but none of those films had gone about things in quite the way she went. One of the foremost names in Polish cinema history, Holland opted to tackle the Holocaust as a theater of the absurd: In telling the fact-based story of Solomon Perel, a German Jewish boy who hid his identity and joined the Hitler Youth to survive, she mixed various disparate genres and tones to render Solomon's life as a fractured, prismatic tragedy of meaninglessness and rootlessness.

Throughout the film, Solomon's (Marco Hofschneider) identity keeps shifting: First he is a German Jew, then he is Polish, then he is a Soviet, then he is a Nazi. Holland plays with expectations, infusing the film with uneasy romance and black comedy where she knows the audience isn't primed to expect them — while nonetheless keeping a clear, consistent, fiercely sympathetic emphasis on the sheer monstrosity of what Solomon is being made to endure by the Nazis. Her point, however obliquely and irreverently made, is clear: World War II was a cruel, twisted farce wrought by the futility of nationalism. The movie doesn't dwell on anything for very long, following Solomon with a sense of gripping, relentless immediacy as he runs from new life to new life in the name of survival. But it's impossible to watch it and not get swept up in Holland's righteous rage — even when it's manifested through a bitter snicker.

Dr. Strangelove

Leave it to Stanley Kubrick to make one of the most ferocious anti-war statements in film history by way of a movie that virtually never depicts any active combat. Sometimes thought of as Kubrick's "exercise in comedy," 1964's "Dr. Strangelove" is no less harrowing than Kubrick's other films when it comes down to it. Indeed, it could be described as a hilarious film about horrible, horrible things.

Those horrible things come in the form of myriad political repercussions that unfold when a United States Brigadier General (Sterling Hayden) goes insane. Rambling, paranoid, and impervious to reason, the brigadier general puts into practice a plan to bomb the Soviet Union against the wishes of either the American or Soviet governments. Thus begins a desperate race against the clock as various U.S. government officials attempt to stop the bombing before the world gets plunged into a nuclear doomsday.

Aided by Peter Sellers playing several of Kubrick's most iconic characters at once, the director parodies the very nature of war cinema, turning the usual identification- and suspense-building devices of war movies on their head: A room of stuffy bureaucrats become humanity's last hope, a plucky aircraft that resists being shot down becomes a harbinger of doom, a climatic show of all-American courage and heroism becomes an act of oblivious villainy. The message lies in the negative space of militaristic ideology — in the enervating madness of everything being left unsaid or unaddressed, as protocols and jingoistic sentiments take precedence again and again over the basic value of human life.

In the Loop

Speaking of wickedly clever war comedies, there's an argument to be made that the definitive film about the martial climate of the 21st century so far is not any pulse-pounding action thriller set in the frontlines of combat, but a spin-off of a BBC workplace sitcom. If that sounds absurd, wait until you watch what happens in the movie.

The movie in question is, of course, Armando Iannucci's "In the Loop," which adapts several characters from "The Thick of It" (one of the best TV shows on Peacock, incidentally) while bringing them into the fold of an international political comedy with stakes as high as the stakes of any political comedy can be. Without saying the names of any conflicts or invasion targets out loud, the movie satirizes the process by which the U.S. and U.K. governments joined forces to invade Iraq in 2003.

In "In the Loop," the brewing of "conflict in the Middle East" manifests as an unstoppable maelstrom laying waste to all forces of reason, morality, common sense, and international opposition. With Peter Capaldi's profanity-prone Malcolm Tucker as our guide through a large ensemble of hapless and/or pathetic figures occupying varying levels of authority, the movie takes on the contours of a tragedy. "In the Loop" barels helplessly towards an unspeakably dark and despondent conclusion, even as the few minimally sympathetic characters do everything in their power to stop the runaway train. However, the laughs are so constant and so rapturous that you almost don't notice.

Camp de Thiaroye

Ousmane Sembène dedicated his career to constructing a new kind of cinema unconstrained by the normative structures, vices, and hypocrisies of Western taste. His mission resulted in numerous clear-eyed masterpieces — films that feel like unlocking new reaches of conscience. 1988's "Camp de Thiaroye," which Sembène co-directed with fellow Senegalese film pioneer Thierno Faty Sow, demonstrates as much: It's a war movie with the ability to make almost every European project in the genre look tame and stale by comparison.

Diligently historical, the film chronicles the 1944 Thiaroye massacre, in which a vast number of West African soldiers conscripted into the French army were murdered by French officers upon returning to Africa, as retaliation for organizing to demand better conditions at the Thiaroye military camp near Dakar, Senegal. In addition to being one of Sembène's most fluent and proficient works — he had been making films for 25 years at that point, and "Camp de Thiaroye" marked his return to the director's chair following an 11-year hiatus — the film is mercilessly incisive in its epistemological import.

With patient processual analysis and images of violence that claw into the mind while still preserving the humanity of the slaughtered, Sembène and Sow demonstrate the inherent insanity of France's wartime belief system. They saw themselves as history's heroes for fighting the Nazis, yet were willing to dispense equally psychotic treatment to those under the boot of the French Colonial Empire — even those who had put their lives on the line to assist in that very same "heroism." In "Camp de Thiaroye," war is a moral disease.

Rome, Open City

After the end of World War II, Italian neorealist luminary Roberto Rossellini made what became known as his "war trilogy," comprising 1945's "Rome, Open City," 1946's "Paisan," and 1948's "Germany, Year Zero." The three films are all must-see visions of the World War II Axis as seen through the horrified eyes of a man on the inside, but "Rome, Open City" has particular urgency — cinematically, as a showcase of neorealism at its most powerful and rigorous, and politically, as a document of what life was like on the ground in the final days of the Nazi occupation of Italy.

Shot with largely non-professional actors on the actual streets of Rome just mere months after the Nazis abandoned the city, "Rome, Open City" pulsates with raucous life. More than just a war film, it's a thoughtful and textured ensemble drama about various characters with intersecting lives in a bustling metropolis: The residents of a boarding house, a Catholic priest, a dejected cabaret worker, and her peppy roommate. Then, on top of that intensely human foundation, Rossellini layers a grim and rage-filled portrayal of the occupation: The Nazis and their spineless or gullible Italian collaborators, the dogged Resistance fighters and their strained families, the kids trying to help as best they can. The film is like an open wound, capturing in real time the still-lingering effects of fascism and warmongering on a ravaged city and its weary inhabitants; you won't find another neorealist film that better honors the movement's humanist ethic.