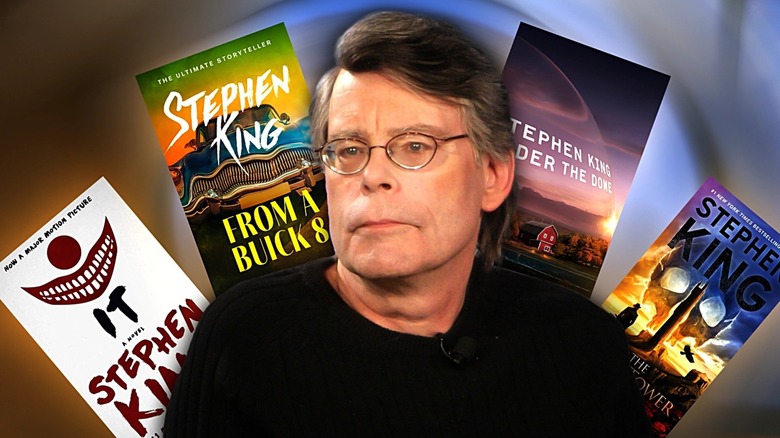

10 Worst Stephen King Endings, Ranked

More than one wiseguy writer has uttered some variant on, "It's the journey, not the destination," but let's be honest: If you trek a thousand miles through some of the most beautiful, strange, and intriguing landscapes on Earth only to end up at a Burger King, you may wonder why you've endured so much for a lukewarm box of chicken fries. Sticking the landing is a nightmare for every creator, but not everyone can take the occasional wet plop with aplomb like Stephen King can. King is an endurance runner of a writer, and no matter the ending, he still gets us to enjoy our journey with him. That's one of his biggest skills, and it's also the one that always gets us lining up for his next book.

King will also be the first to admit when the ending gets away from him, either from some late game writer's block, or because he was deep in his drug era. But he never worries about that, either, and on the whole, most of his endings make better sense in context than we give them credit for. Still, there's no argument that some of his endings are, well, just bad. We're here to talk about the worst finales Sai King has unleashed on his fandom.

Let's head on down that long road with Mr. King and talk about what works and what really doesn't. Spoilers are to be expected, since we're digging into the 10 worst Stephen King endings.

10. The Dark Tower

"The Dark Tower," as both saga and final novel, is King's magnum opus. It's a sprawling piece that ties the majority of King's works into a larger universe, and its ending is one of the most nuanced and divisive in fiction. In point of fact, "The Dark Tower" has two clearly labeled endings. The first is when Susannah Dean is offered her chance at happiness, by walking away from Roland's single-minded quest to find her own ending. The second is Roland's realization that his journey cannot end yet. The man in black is once again fleeing across the desert and he must follow. But Roland has also grown from his journeys, and this may well be his last time chained to his fate.

The nuance here, or perhaps it's a meta joke by King, is that for his Constant Readers, Susannah's departure is the happy ending we deserve. We followed Roland's ka-tet through despair and death, and knowing there's a universe where they'll be all right is a just reward. But it's not a reward Roland has earned, and it's easy for readers to feel cheated when his story doesn't end. Since it's a Herculean task to not read past Susannah's departure, we inevitably walk into the trap alongside Roland.

Are we right to feel cheated? That's entirely on how clear the finales of "The Dark Tower" read to you. On the whole, it does work. But it's subtle and the last trick still infuriates. The finale of the saga may not be a downright "bad" ending, but the years of slap fights after make it hard to love blindly.

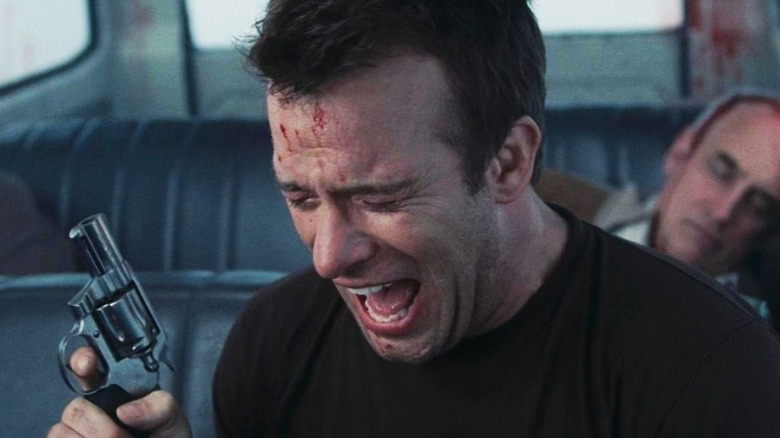

9. The Mist

The chunky novella that opens the "Skeleton Crew" anthology is another ending that's not traditionally "bad." The issue is, the infamously grim film adaptation of "The Mist" (seen above) by director Frank Darabont blows King's ending so far out of the water that even King himself remains impressed by it. It's a logical conclusion set up by the novella, although here, it's been taken to the bleakest limit.

"The Mist" retains the same premise in both versions. After a strange, destructive storm, a group of survivors wind up trapped in a supermarket as horrific things surge out of the mist to whittle away at them. Eventually, plans to escape are fomented, enacted, and the novella, while still pessimistic, leaves Dave, his son, and a couple of others out on the road, looking for other signs of human life. The only clue may lie in radio static, where we might just be hearing what we want to hear.

It's not bad, but it is a waffly thing that leaves far too much to our imaginations. Do they make it? Does Dave end it all before the creatures get them? Here, Darabont offers a clear answer, and then chases it with a minute of horror that left even hardened King fans reeling: Dave "saves" his son and his friends from the monsters with the few bullets he has left, only to discover they were minutes away from salvation. It's the second ending to show Darabont's talent at interpreting and bettering King, as it was also Darabont that added that final, beautiful shot to "The Shawshank Redemption."

8. Under the Dome

"Under the Dome" isn't subtle about its ecological and sociological themes. A small town, trapped in a bottle-world, sees its flaws and divisions amplified in such a blatant way that Rod Serling could've adapted this bad boy in thirty minutes or less. He pretty much did, too, with classic "The Twilight Zone" episodes "The Monsters are Due on Maple Street" and "The Shelter" hitting a lot of the same notes as Stephen King does here.

It doesn't take long to find out which of your neighbors you can't trust when things go wrong, but it does take most of the novel to suss out why the domed town is in this predicament in the first place. The answer is another Serling-style special, and after all the too-realistic cruelties our characters have suffered, it's easy to feel it's out of place. The now-asphyxiating town is just an ant farm to a bunch of alien kids, and once one of our protagonists gets one of these dweebs to realize they're torturing sentient lives, the ordeal ends. If you grew up on chewy pulp science fiction, like King did, it's not that bad in context. But it's certainly a choice, and not one that ages well with audiences that would prefer at least some tonal consistency.

7. The Langoliers

One of four terrific novellas found in the "Four Past Midnight" collection, "The Langoliers" is a slow-cooking stew of character drama and cosmic horror. King's array of characters are catnip to fans of his big ensemble sagas, featuring familiar specialities like the mysterious agent, the tortured widower, the psychic child, the irredeemable a-hole, and many more. Once they're established and begin intricately dealing with each other, the real problem comes back to the foreground: nobody's flying the plane, a bunch of passengers are missing, and where the hell are they, exactly?

The answer is that they're between; lost in time and, to a much lesser degree, space. For reasons left purposely vague, our heroes find themselves lost in a temporal rift. From there, it's time to "Survivor" their way out of a sticky situation before this patch of lost time disappears entirely. Here's the chunky part: For whatever reason, disposing of a dead patch of time is handled by temporal munchie boys that are left as ominous chewing noises through most of the story. The raging jerk, Toomy, calls them Langoliers in reference to his abusive father's favorite nightmare bedtime story. That part's fine. The problem is that King, forgetting what every no-budget horror filmmaker eventually learns, eventually describes the Langoliers.

They're meatball chain chomps. That's all they are. Even funnier, the 1995 miniseries adaptation (one of the worst takes on King's work) shows the damn things in all their hilarious rotoscoped glory. "The Langoliers" remains one of King's best novellas... for about 95% of its reading time.

6. The Stand

Stephen King's first epic, "The Stand" is a hearty 1,100 pages in its 1990 hardcover edition. The average paperback copy is even longer, printed on the thinnest paper humanity's invented. Within those pages is a seminal urban dark fantasy, full of characters scraping their way out of an apocalyptic first half of deadly disease and dissolving society, and rebuilding in the face of a new nightmare in the second. Elements of the mystical drift in, offered by strange dreams, a nightmarish man walking the world's streets, and that unfortunate King speciality, a God-touched Black woman whose visions will help rebuild a good-natured society in Boulder, Colorado.

A good fantasy epic means our heroes have to throw down with the forces of Evil eventually, and sure enough, God charges several of Boulder's finest with taking a hard and downright Biblical journey west to Sodom... err, Las Vegas (naturally), where the Walking Dude and his henchmen have started their own, less friendly, society.

King does the work in baking a religious motif that's important yet relatively inoffensive to the agnostic and atheist, but the final showdown still rips all agency from its characters and reduces everyone to witnessing the literal Hand of God coming down to sort this situation out. You know. After the majority of the world died miserably. Thanks for coming in clutch, YHVH.

The final insult is more "Dark Tower"-style annoyance. The Walking Dude wakes up among a primitive tribe, having learned nothing, and resumes his usual games. Technically, the point is a good one: evil never learns, and evil always repeats. But combined with a massive, enjoyable epic, and the actual deus ex machina of God's intervention, it's a little weak.

5. The Tommyknockers

"The Tommyknockers" isn't considered one of Stephen King's best works, and that's a rating that comes from King himself. In an interview with Rolling Stone, King flatly calls it "awful," though he also acknowledges that there's some good ideas in it. If King has one true pulp trash sci-fi novel, "The Tommyknockers" is it. Yet it's still an enjoyable read, approached with the right mindset (we suggest high comedy), and some fans — including this one–— return to it on occasion to revel in its drug-addled messiness and the occasional genuinely banger chapter. None of this excuses the gag punchline or the book's premise.

The premise? What if the first aliens we ever get to encounter were genuinely stupid? Boy, are they. Capable of enough technological brilliance for space travel and what's either body-surfing or forced evolution, but not enough insight to think about long term consequences — what in the Silicon Valley is this? — a changing population is bumbling through dangerous and silly mistakes all to fix up their beater space-car and take off again. Not only does this involve a hilarious slap fight over these idiots fixating on disposable batteries to run all their neat tech, which would be enough to for them to kill themselves before too long, but here's the punchline: They can't even stop the town drunk from carjacking their ride and stopping pretty much all of them in one fell swoop. A five alarm dumpster fire, both novel and ending. Bring s'mores.

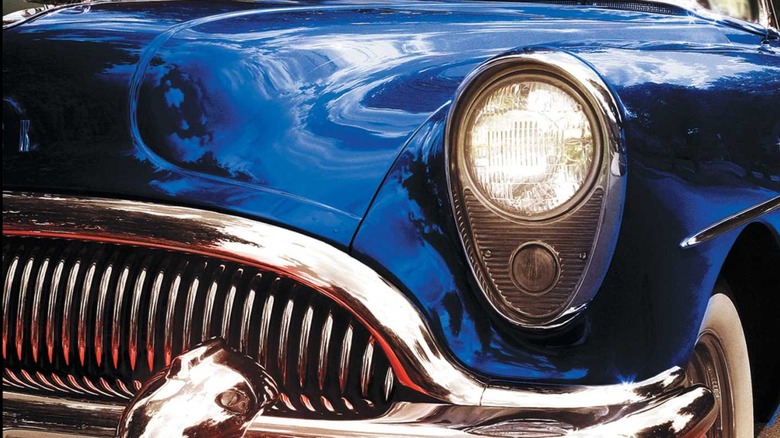

4. From a Buick 8

"From a Buick 8," was printed in 2002, and like "Christine," features a strange and deadly car. It's fine, so long as the reader goes in looking for a "Creepshow" style experience where not much happens, punctuated by some fairly weird moments. Then it meanders towards an ending. If "The Color Out of Space" was boring incarnate, it might have looked like a Buick 8 Roadmaster.

Of course, this car isn't really a car. It's an object that looks like a car, and maybe it's an inter-dimensional portal. A couple of people go missing. Sometimes the car-thing puts on a lightshow. Eventually one of our protagonists, a grieving kid named Ned, decides to destroy the car-thing. Except this might be what the car wants, in order to eat the kid. Or something.

In any case, the situation does resolve and Ned turns out okay, and the car? The car is shoved into a garage where they wait for it to die, like a school goldfish over a long summer. Of all the Stephen King novels ever written, "From a Buick 8" is definitely one of them. Its ending is a passive, meaningless cap to whatever the car was supposed to represent to humanity. An annoyance, apparently, and not much more.

3. Cell

"Cell" is the rare King novel that already reads like a TV movie of the week designed around whatever cultural fear mongering is popular at the time. In this case the fear is, not unreasonably, cell phones. A hijacked signal is turning people into psychic zombies, flocking together against the unchanged zombie-hunters. It leaves everyone in a state somewhere between the vampires of "Salem's Lot" and Richard Matheson's evolved humans in "I Am Legend."

It's another case where King's blatant opinions certainly aren't wrong — look at the state of social media and tell us this isn't its own kind of pulse degrading our connections with each other — but he flails once he gets to the end. After surviving weeks on the road, dogged by violence and the rare glimpse of hope, our protagonist Clayton is reunited with his son. But Johnny's been hit with the cell pulse, leaving him a shambler. By now, the pulse is corrupted, and in a fit of desperation, Clayton attempts to use the fading signal to reboot his son's brain. Does it work? LOL. Wouldn't you like to know? Because that's where the book ends, with a bad cliffhanger.

2. Dreamcatcher

An alien force is hunting a small town, and it's only the latest attempt by this species to cut its way through humanity. All others were suppressed by the government. The only hope this time may lay with a mentally disabled individual who instinctively understands the threat. This is the plot of two pretty bad stories. One is 2018's "The Predator," directed by Shane Black, and the other is King's "Dreamcatcher." There's a lot we could say about "The Predator" and its disgusting reliance on a weird, ableist idea of autism, but at least it didn't have butt aliens.

The butt aliens are only one haywire thing about a novel with all the bizarreness of "The Tommyknockers" but none of the dumb charm. Its "magical" child is a young man with Down's Syndrome, nicknamed Duddits by his friends. Duddits' childlike innocence (another ugly stereotype) leaves him open to psychic powers, and it's that connection to his friends that ultimately helps save the world from butt aliens.

The finale is incoherent, taking place in a mental construct sort of like the often culturally misappropriated Ojibwe dreamcatcher, a symbolic spider's web meant to protect the dreamer. Stephen King doesn't like this one either, and he's right to say it. The "Space Raptor Butt" stories by Chuck Tingle are far better if you need butt aliens in your life, and we are not saying that ironically.

1. It

We all knew "It" was coming, but it's not entirely for the reasons fans expect. It's definitely part of the problem: Lost, hurt, and exhausted from battling the cosmic horror known only as It, Beverly comes up with a hell of a way to spiritually reunite her group of friends and get them out of the sewers. Yes, it's the kiddie bang scene, and there was a good idea in here somewhere about the conflicts between innocence and wisdom that's utterly drowned by the fact that it's a bunch of kids having sex in a sewer.

But that's only part of the ending, as the parallel story moves on with the adults. In the real finale, many years later, the few survivors of round two — with It, not each other — drift away to live the rest of their lives. But Bill, our writer hero, has one more little bit of magic in him. He's bringing his comatose wife back to the land of the living with the power of a kid's bike. And his erection. Yup, the triumphant final moments of "It" contain a crotch grab and a romantic kiss. It sort of works in context, but the whole stew mixes up maturity and sexuality into a gumbo of uncomfortable mess. "It" has an infamously rough finale, but there's so much more to that problem than the sewer sex alone.