The Obscure Batman Comic That Inspired Christopher Nolan's Dark Knight

In Christopher Nolan's "Batman Begins," the defining question of the film is: "Why do we fall?" The answer, which Bruce Wayne (Christian Bale) learns again and again, is "So we can learn to pick ourselves back up."

The commonly cited influence on "Batman Begins" is "Batman: Year One" by Frank Miller and David Mazzucchelli, the definitive origin of Batman. The other two parts of the "Dark Knight" trilogy have been similarly tied to famous Batman stories: "The Dark Knight" is "The Long Halloween" plus "The Killing Joke," featuring a Joker (Heath Ledger) who wants to break Gotham City's soul and succeeds in turning Harvey Dent (Aaron Eckhart) into Two-Face. Then "The Dark Knight Rises" closes out the myth by combining "Knightfall," "The Dark Knight Returns," and "No Man's Land" to bring Batman low so he can climb back up to meet his greatest and last challenge.

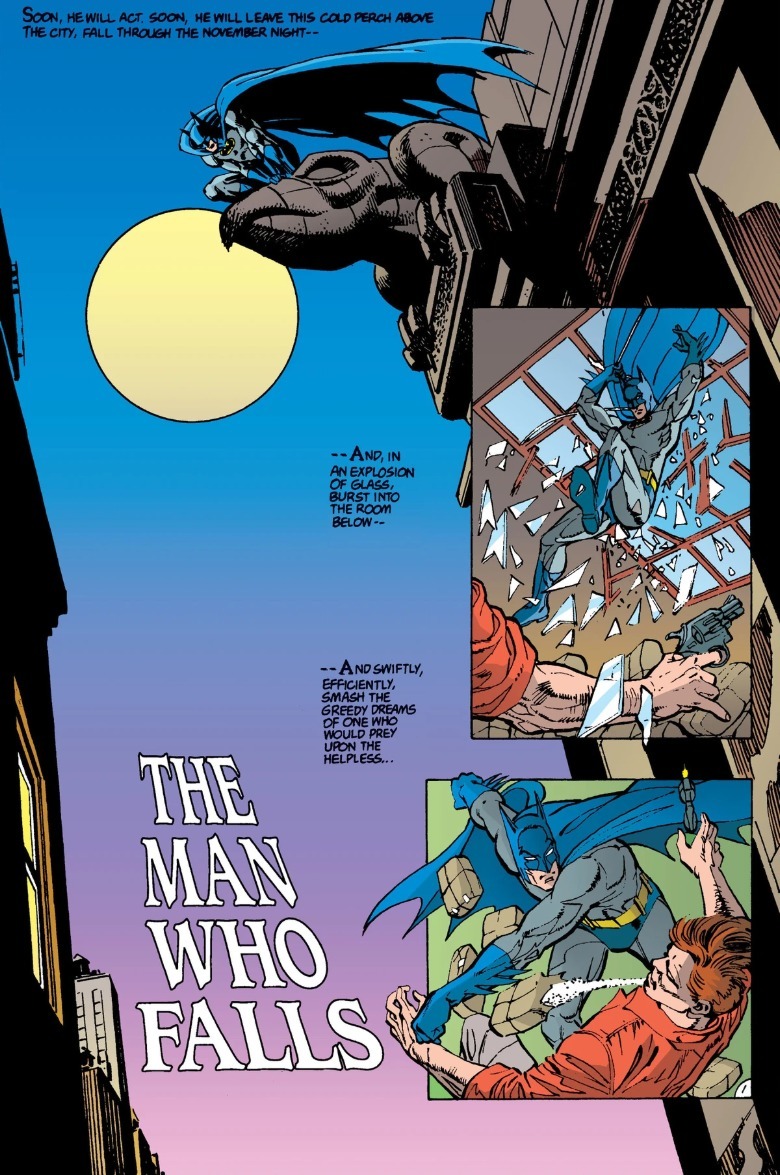

But is there another Batman comic in this tapestry, one less famous than the others? That would be 1989's "The Man Who Falls," by writer Dennis O'Neil and artist Dick Giordano. In a mere 16 pages, the comic tells Batman's life story from past to present. Beginning in media res, Batman is "the man who falls" in the literal sense, crashing through skylights to terrify criminals.

Then, the comic returns to Bruce Wayne's childhood; shortly before his parents' murder, he falls into a cave full of bats. After losing his parents, Bruce travels all around the world, learning martial arts, criminology, and escape artistry while slowly deciding how he will wage his war against crime.

"The Man Who Falls" was first published not as a single comic issue, but as a chapter in the "Secret Origins of the World's Greatest Super-Heroes" collection. In 1986, DC Comics rebooted its universe and updated its characters' origins. Fresh off his run on "Daredevil," Miller reinvented Batman with "The Dark Knight Returns" and got to restart his journey with "Year One."

"The Man Who Falls" works in the shadows of Miller's Batman. "Dark Knight Returns" was the first story to depict Bruce falling into a batcave as a boy. In "Year One" and "The Man Who Falls," Bruce tries to go out crime-fighting in Gotham's red-light district with no mask and it ends in "dismal failure." Resting at home, a bat crashes through his window and he realizes what he must become.

Due to the comic's original publication, "The Man Who Falls" remains much more obscure, and harder to find, than Miller's Batman projects — or Nolan's.

How Christopher Nolan came to understand Batman

In the "Genesis of The Bat" DVD featurette for "Batman Begins," director Christopher Nolan and writer David Goyer discussed how they drew on Batman's comic history for their film. They decided to tell Batman's origin because there had not been a definitive depiction of that onscreen before. There was a point A (young Bruce Wayne sees his parents die in front of him) and point B ("I am vengeance, I am the night, I am Batman!"), but between those points was a gap. Audiences knew why Bruce Wayne became Batman, but not how. Nolan would answer that, down to detailed explanations and rationale for all of Batman's fantastic equipment.

For the film's villains, Nolan and Goyer drew on the aforementioned "Long Halloween" for Scarecrow (Cillian Murphy). Then, they looked back to O'Neil's 1970s Batman comics (drawn by Neal Adams), which introduced eco-terrorist Ra's Al Ghul and his League of Assassins. Liam Neeson would portray Ra's in "Batman Begins" — the film merged the villain with the comic character Henri Ducard, a French investigator who taught Bruce Wayne how to be the World's Greatest Detective.

As Nolan did his research, "The Man Who Falls" was the comic that most helped him understand the essence of Batman's character. It also helped him understand what he wanted to adapt about the character. To quote Nolan directly:

"The jumping off point for me, really, had been a story called 'The Man Who Falls' and, it suggests various points along the development of Bruce Wayne into Batman, this idea that he travels the world and is mentored and tutored by various individuals in different disciplines and then returns to Gotham. For me it was a fascinating story and a fascinating connection between Bruce's early childhood trauma, falling down this well and being attacked by these bats, and then the persona that he develops in order to use people's fear against them."

From there, Nolan and Goyer didn't just use "The Man Who Falls" as the blueprint for their film's story structure; they also imported the comic's understanding of who Batman is. Who is that? Just read the title back again.

The Man Who Falls is the original Batman Begins

The first act of "Batman Begins" is "The Man Who Falls," though with some differences. Once the flashbacks start in the comic, the story flows chronologically. "Batman Begins," on the other hand, cuts back and forth between Bruce's childhood and his present circumstances where he's stranded in Tibet (first in prison and then training with the League of Shadows under "Ducard").

Despite the more complex structure, Nolan's movie streamlines Bruce's training; he spends years aimlessly wandering Europe and Asia, living in poverty to understand the desperation of criminals. It's only when he gets to the League of Shadows that he begins to focus his rage on a mission and picks up everything he needs to be Batman.

In "The Man Who Falls," however, Bruce learns from many different teachers. He studies martial arts with a Korean master named Kirigi. Bruce excels in mastering his body, but Kirigi claims that taming the anger inside him will take 20 years — time that Bruce does not have, if he even wanted to forget his rage at all. When he travels to France, Bruce then witnesses Ducard killing a fugitive they'd been tracking and decides that brutality is a step too far; his war, Bruce decides, is one where he will save even his enemies' lives.

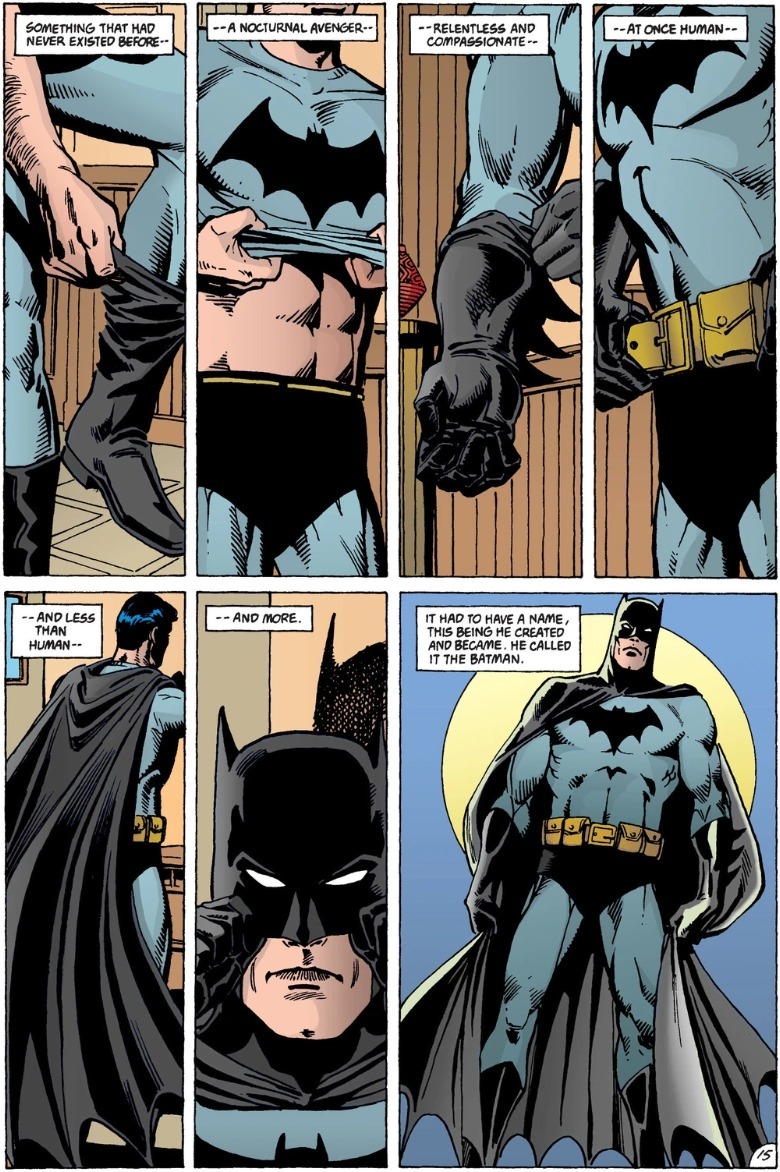

When Bruce finally becomes Batman in "The Man Who Falls," the narration puts some distance between our protagonist and the mask he now wears. Batman isn't merely Bruce Wayne in a costume, but something more entirely.

The overarching, movie-to-movie theme of the "Dark Knight" trilogy is that Batman is more than a man. Bruce begins his quest not thinking that Batman can single-handedly fix Gotham, but instead that he can inspire the rest of Gotham through his theatrical heroics. Batman is a symbol — but Bruce Wayne is a man, and a man can fall.

In "The Dark Knight Rises," Bruce tries to step back into being Batman after an eight-year hiatus. He stumbles, and to devote himself fully to an unbreakable ideal, he must once more climb out of a pit like the one he tumbled into as a boy. This time, his father doesn't come to lift him out of the pit; he must climb out on his own.

"The Man Who Falls" concludes that Bruce Wayne "falls" every day. By being Batman, Bruce plunges straight into his darkest self, constantly reliving his parents' death and embodying his own childhood fear. But no matter how dark he gets, he never takes a life, because he understands that criminals are often just desperate people who need help to climb out of their own worst selves.

Even when Batman falls, he always rises back up.