10 Things That Happen In Every Star Trek Movie Or TV Series

"Star Trek" has diversified a lot over the years, in keeping with the Vulcan mantra of infinite diversity in infinite combinations. We've seen Captains of all genders, races, and even species. There's been serious wartime Trek ("Deep Space Nine"), post-apocalypse Trek ("First Contact" and "Discovery," in very different ways), Suicide Squad Trek ("Section 31"), and even comedy Trek ("Lower Decks").

Across every iteration, though, some things have to remain the same, or it's just not "Star Trek." We're not just talking about the most common tropes in the franchise, like the guys in red shirts (here's the different meanings of "Star Trek" uniform colors by the way) who used to beam down with Kirk and Spock to get killed every other week — once fans caught on about that being a thing, subsequent shows stopped doing it. This is about things that still happen in every iteration.

Every franchise has its favorite structures and character types, but when one really breaks it down, "Star Trek," any version, arguably the greatest sci-fi franchise of all time, has a formula that makes it what it is. Whether we're talking about the movies, the reboot, the Paramount+ original streaming shows, or any other iteration, there's a pattern that the story has to follow to really feel like it belongs. There are broad strokes that just happen every time — and these are the ten things that happen in every "Star Trek" movie or TV series. Memorize them, and maybe you can write the next great "Star Trek" story.

A log entry, read aloud

Classic "Star Trek" began every week with William Shatner as Captain Kirk saying, "Captain's log, stardate..." followed by a string of numbers. Originally, those numbers were more or less random; later, as Gene Roddenberry realized how detail-oriented his fans were, they started representing actual calendar dates. Regardless, by getting the words "Captain" and "stardate" out there upfront, the show signals to channel-surfers exactly what it is: a spaceship show. Nowadays, there's probably nobody watching TV who doesn't have any idea what "Star Trek" is, but in case there are, the tradition continues. It's also a quick shorthand to deliver the episode's basic set-up, admittedly breaking the basic screenwriting rule of "show, don't tell" in order to get to the action faster. (But remember, there's always a trick to recording a great ship log.)

It's not always the Captain doing the reading any more. When a show is guaranteed multiple seasons, the writers want to do some non-Captain stories, especially if the show doesn't even feature a Captain. Benjamin Sisko was a Commander on "Deep Space Nine" before finally getting promoted, and Bradward Boimler on "Lower Decks" imagines his log recordings to be more important than they are. In an intellectual-leaning franchise like "Trek," though, everyone in a position of authority has an inner monologue, and the log is a viewer's way into it more often than not. The writers have also learned that if they don't want to calculate the actual stardate, they can just say "supplemental" instead.

A mission of exploration, diplomacy, or war is laid out

The mission statement of "Star Trek" is "To boldly go where no man/one has gone before." As such, a majority of episodes deal with explorations and run-ins with new cultures. If they don't, they're generally about missions of either diplomacy or war. Even if an episode doesn't seem to fall into one of those three blanket categories, it usually does: characters going on vacation are either exploring or being diplomatic; and characters who find themselves in strange situations with amnesia, or waking up as seemingly new characters, are ultimately exploring.

Gene Roddenberry was less fond of war, as his goal was to paint an optimistic vision of the future. Yet even the original show had military moments: "Balance of Terror," which introduced Mark Lenard and showed us what Romulans looked like for the first time, is a classic submarine battle tale in space. Klingons, before they became honorable allies, were treacherous, warlike villains essentially representing the real-life Soviet threat at the time. "Deep Space Nine," stuck in orbit around Bajor, might have seemed pretty limited if not for the nearby wormhole, which allowed for many missions of exploration, as well as an existential threat represented by the Dominion.

"Discovery," via time travel, went from Klingon War-based missions to exploring the far future. The balance of peaceful versus aggressive missions originates with Roddenberry's struggles with network executives who wanted action, and that tension created the tone that all spinoffs have followed.

Someone (or something) is beamed up

What lightsabers are to "Star Wars," the transporter is to "Star Trek": the one piece of fictional technology that defines the franchise in people's minds. It shows in their most popular command catchphrases, too: "Use the Force, Luke" versus "Beam me up, Scotty." (Never mind that the latter order was never actually phrased that way on the show — "Star Trek" trademarked it anyway.)

The transporter beam just might be the most classic example of budgetary limits increasing creativity. It would have been too expensive and time-consuming to show the Enterprise landing on a new planet every week, so "Star Trek" transporters became an elegant solution with a practical purpose, and one that could be achieved cheaply without looking too cheesy. "Star Wars" shows and movies, ever since the Special Editions, have gone out of their way to show spaceships landing, and it's ultimately just a visual effects flex that takes up airtime. "Star Trek" movies and shows, while occasionally — mostly under J.J. Abrams — showing off their budgets by having the Enterprise take off and land, keep on beaming people up and down.

"Enterprise," which is chronologically the earliest show so far in the Trek timeline, had to show things developing, and as such didn't beam people up right away. They used it from the very beginning to transport inanimate matter, though. As different as that show tried to be, they weren't crazy enough to not beam things up and down.

Not everything is as it seems

From the original pilot "The Cage" to the secret traitor in "Section 31," every "Star Trek" has something that isn't what it first looks like. That giant cloud threatening to destroy Earth? It's just our old space probe coming home to meet the family (who might be humans, or extinct whales). Those creepy plastic surgery aliens who hate the fountain of youth planet? It's because they're actually the same species! Trek loves ironic reveals just as much as its contemporary, "The Twilight Zone," with which it shared several stars (check out the best actors "Star Trek" actors who appeared on "Twilight Zone").

If there's a planet that at first seems peaceful, bet the life of two redshirts that it's not. Does a new species seem warlike and dangerous? Humans probably just misunderstood their culture (or, in the case of the adversarial Jem'Hadar, didn't realize they're all bred to be strung out on space cocaine).

Gene Roddenberry was making the point that we shouldn't default to hating and fearing things that seem different, and we should check our own privileged notions of what seems harmless. Even when post-Roddenberry Trek went to full-scale war with "Deep Space Nine," however, the conflict managed to keep that element of subverting expectations by having the enemy be shape-shifters who could look like anything or anyone. Q in particular loves to mess with humans on this exact principle.

A non-human crew member is puzzled by human responses

Ever since Mr. Spock became the breakout star of the original series, every "Star Trek" crew has been sure to have at least one member who isn't quite human. They may be alien, android, living hologram, or perhaps half-human, but in every case they serve as commentary on human behavior, mostly by failing to understand emotions or irrationality.

Many of them come at it from a perspective of wanting to be fully human, like Data on "The Next Generation," or the Doctor and Seven of Nine on "Voyager." Others, like the half-Vulcan Spock and the fully Klingon (but human-adopted) Worf, proudly proclaim their alien heritage. Some are a mixture — Neelix on "Voyager" mostly wants to fit in, and perhaps understand human taste buds a bit better, while T'Pol on "Enterprise" goes from disdain to love with at least one human in particular. Almost all of them get a marketable catchphrase, from "Highly illogical" to "I am a Klingon!" or "Curious."

For adults, the non-human characters represent extreme personalities they may find familiar. Neuro-atypical fans often find a connection with Data, while Worf is often played as a goof on alpha male athlete types. For kids, aliens are proof that this isn't just a dry science show, and that it has cool and unusual characters that don't exist in reality.

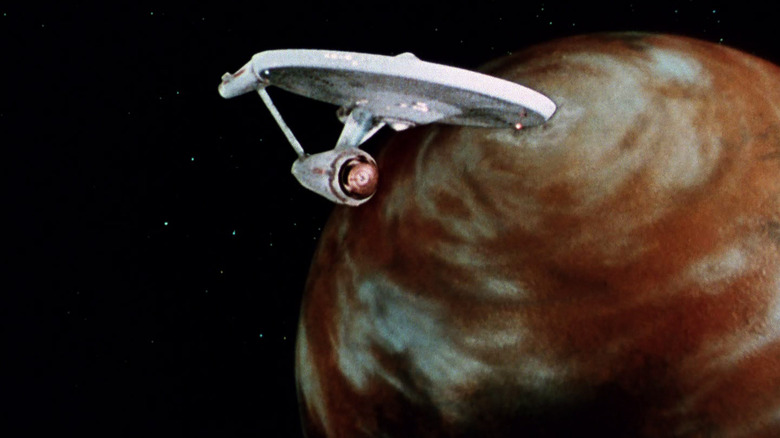

The primary vehicle is shown in orbit around a planet

Back in the '60s, every time the show came back from commercial breaks, we'd see the Enterprise flying above the planet at hand. As with the Captain's log intro, this was a way to let channel-hoppers know immediately that they'd tuned in to a sci-fi show. It's been the tradition of every Enterprise since to do likewise, although the streaming shows and the movies don't necessarily have commercial breaks. The orbit establishes spatial geography, and makes for an easy cutaway transition to show time passing, if the writers can't find a more organic way to pull it off.

"Deep Space Nine" had the issue of taking place in a space station, but that certainly didn't stop establishing shots of it above Bajor from becoming commonplace. In episodes not involving the station, the Defiant or the Runabout would be seen in orbit, depending which one was in use for that particular story.

For "Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home," the Klingon Bird of Prey used by the crew actually landed on the planet, but orbit played a role anyway, as it took a specific orbit around the sun to time travel. They also still found a way to justify transporters — you can't just let humpback whales swim aboard, after all.

A challenge must be overcome, even if the characters don't know it

Whatever the initial mission is, the challenge that presents itself will usually be something that wasn't anticipated — or if it was, it will have a surprise element. Even the most basic one-on-one physical battle, like Kirk versus the Gorn in "Arena," turns out to have been a test of mercy rather than killing ability. On the other hand, any jaunts by crew members to the pleasure planet Risa usually end in something dramatic happening to interrupt any attempt at leisure, like a religious uprising or archaeological quest. In fact, any attempt by any "Trek" character to take a vacation is bound to end in unexpected trouble.

The most straightforward that "Star Trek" plots get is the frequent "Wrath of Khan" formula, in which a pre-existing enemy — actual or retconned — engages in a revenge quest against a primary crew member. Even there, though, there'll usually be a surprise element to make it work — Data being seduced by the Borg queen in "First Contact," or Philippa Georgiou in "Section 31" realizing her old flame is the real villain.

Gene Roddenberry's love of things not being as they seem extends to missions as well. The initial goal is rarely the final one, but even if it is, something our heroes don't know upfront will become key to beating it.

The solution favors intellect over violence, though violence may be necessary

If "Star Trek" characters could prevail by force alone, Worf would have been made the top Captain long ago. Rare is the Trek dilemma that can be solved just through violence. Gene Roddenberry was so anti-violence towards the end of his life that he mandated that "Next Generation" characters couldn't have conflicts with each other, despite the fact that McCoy yelling at Spock was one of the best recurring bits on the original series. Indeed, "The Next Generation" kicked off with Q putting the human race on trial for its violent history, and Picard having to use his intellect to solve a mystery in order to prove we'd progressed as a species.

Humanity faced a few setbacks after that, like the Dominion War of "Deep Space Nine," and the need for Janeway to conserve resources on "Voyager." Yet even when battles occur, outthinking the opponent is more key to victory than superior firepower. Khan's two-dimensional thinking was his downfall, Data faked out the Borg queen, and the crew of "Discovery" had to tread very carefully with a psychokinetic Kelpien to save the future.

Part of the point of "Star Trek" is that it takes a crew to get things done. Kirk, Spock, and McCoy have temperaments that balance each other out, and every show since has tried some version of that dynamic, from Janeway and Paris to Boimler and Mariner.

A basic moral lesson is learned

God wouldn't need a spaceship. Driving animals to extinction may have unforeseen circumstances. Hatred based on superficial differences could end us if we don't quit it. Invasive, assimilationist cultures are bad, but not beyond redemption. These are but a few of the moral lessons various "Star Trek" movies and shows have had for us over the years and decades.

Then there's Janeway on "Voyager" executing new crew member Tuvix, to try to restore the two beings who accidentally fused to create him. From a TV show perspective, there was no choice in the matter — the cast regulars have to be restored to status quo by the end of each episode (with occasional show-changing exceptions). Morally, though, some fans still call Janeway a murderer for the way she navigated arguably the greatest ethical dilemma in "Star Trek" history.

Perhaps most notoriously, Benjamin Sisko in the "In the Pale Moonlight" episode of "Deep Space Nine" lies about intel to draw the Romulans into the Dominion War as allies, and sanctions murder to protect the secret. When our own politicians lie us into war with fake evidence, we demonize them; when a character we have grown to love does it, we have to look at ourselves a little bit.

Historically, seeking out new civilizations has always been a process fraught with problems. As difficult as true morality may be to find in cultural clashes, "Star Trek" reminds us the best outcomes depend upon our finding it.

Things end with a comedic or sad observation

Like many mainstream episodic TV shows, "Star Trek" in all its forms — including movies — takes a breath after the climax, allowing the characters, and the audience, to process what they've just seen and learned. In some cases, it's a tragic lesson, like internalizing that the needs of the many outweigh the needs of a sacrificial one ("The City on the Edge of Forever" did this even before "The Wrath of Khan" sanctified it). Other times, it's humorous, like Kirk, Spock, and McCoy realizing in "The Apple" that they may have effectively disrupted Eden, and implying Spock looks like Satan. That's an extra meta-joke: network executives were initially concerned that indeed, Spock looked too Satanic.

Tense bottle episodes that force two unlikely companions to bond in a high-stress situation generally end with a comedic look at how the status quo has or has not changed between them. Episodes like "In the Pale Moonlight" allow the Captain to reckon with the morality of a difficult choice, either justifying it or feeling remorse.

It's an extra beat that could be read as a lack of trust in some audience members to get the point, but the more generous reading is that we're allowed to see the decisions sink in. Action, both in drama and real-life, depends on snap decisions. It's the way they sit with us afterward that really defines who we are.