Is Christopher Nolan's Interstellar Scientifically Accurate?

Christopher Nolan is one of the most important directors of his time, and may even be the preeminent filmmaker of his generation. But there's an element to the British director's style that, at times, can make his films seem a little too functional and cold. As Richard Brody wrote in his New Yorker review of "Oppenheimer," "Nolan cuts his scenes to fit together like a jigsaw puzzle, and details that don't fit — contradictions, subtleties, even little random peculiarities — get left out [...] What remains is a movie to be solved rather than lived."

With 2014's "Interstellar," however, the director proved he could balance his functional "jigsaw puzzle" style with real emotional heft. As such, "Interstellar" remains Nolan's emotional masterpiece, and is for many his best film. What makes it a true marvel is that Nolan managed to create a truly moving emotional drama that also happens to be a spectacular sci-fi epic that's even more fixated on scientific accuracy than any of his previous projects.

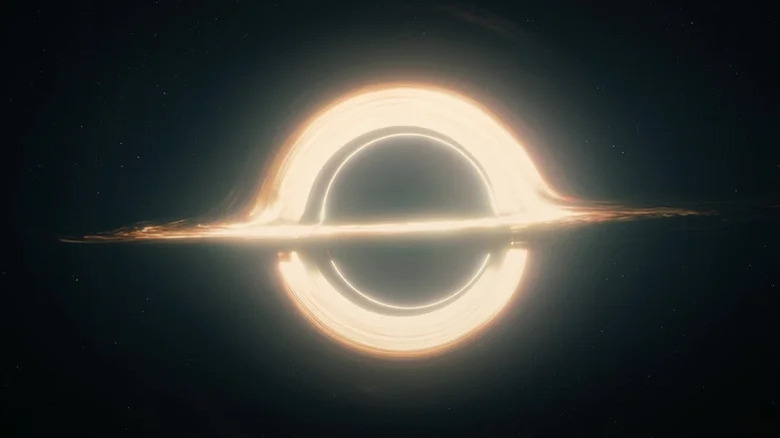

Also impressive is the fact that while Nolan's commitment to scientific realism in "Interstellar" might seem like a way to place limits on his galaxy-spanning sci-fi blockbuster, it actually made for some of the film's most memorable spectacles. From Miller's planet with its giant tidal waves to the fictional supermassive black hole Gargantua, Nolan's film is packed with seemingly fantastical elements that are actually grounded in real science. How accurate is "Interstellar" in that respect? Well, as it turns out, very.

Physicist Kip Thorne ran a tight ship on Interstellar

Most fans of Christopher Nolan will likely know the director hired theoretical physicist Kip Thorne to consult on "Interstellar." But those fans might not realize just how invested in the film's production Thorne was. While Nolan took a giant sci-fi swing with "Interstellar," the presence of a Nobel Prize-winning physicist ensured things never got too far removed from reality. On Neil deGrasse Tyson's StarTalk podcast, the host tried his best to catch Thorne out on several scientific points related to the movie, but the physicist had an answer for all of them.

Firstly, the very premise of "Interstellar" was based on a real scientific possibility. The film revolves around humanity's search for a new host planet as they face extinction on Earth due to crop blights. This is what propels Joseph Cooper (Matthew McConaughey)'s trip across the universe to colonize a new planet. But as Tyson put it to Thorne, "Whatever effort it takes to find another Earth, it seems to me to be a bigger effort than just telling the biologists [to] come up with a serum that could fix the crops."

Thorne had an answer, revealing that the filmmakers brought together "the best biologists" who were "experts on these kinds of things" and after a three to four-hour conversation, none of them could present any reason why a "vicious generalized blight" wouldn't occur. In Thorne's words, "It's something that biologists have never seen but they cannot rule it out." Were such a thing to exist, developing a "serum," as Tyson suggests, that could cure every single type of crop would be out of the question.

This approach to the premise of "Interstellar" is very much indicative of how Nolan and co. approached the entire movie, with Thorne telling Tyson, "it's unlike almost any other film in that these issues were vetted by the world's best experts." Tyson has declared "Moonfall" to be the least scientifically accurate sci-fi film, but he couldn't find any issues with accuracy for "Interstellar," which speaks to the level of Nolan and Thorne's commitment.

Even the sci-fi was more 'sci' than 'fi' in Interstellar

A crop blight might not seem like the most fanciful element of "Interstellar," so how about something that seems a little more science fiction — like, say, a water planet with giant tsunamis? Miller's Planet is the first planet in the system orbiting the black hole Gargantua, and hosts Coop and his crew when they land on the surface to investigate. They are quickly forced to escape, however, when a giant tidal wave emerges on the horizon. The sheer size of the wave itself is unlike anything we would ever see on Earth, but is it entirely unrealistic to think that such a thing could exist on a distant planet?

According to Kip Thorne, the Miller's Planet wave actually does have a fairly strong basis in scientific fact. The physicist revealed on the StarTalk podcast that it is based on a type of wave called a solitary wave, which was discovered by naval architect John Scott Russell in 1834. Russell observed a wave form after a canal barge ran into an underwater obstruction, and noted that it maintained its shape the entire time he followed it on horseback. This is the type of wave shown in "Interstellar," though even Thorne admits that the size of the version in the film is "exaggerated."

Another facet of the Miller's Planet sequence is the extreme time dilation on the world's surface. One hour on the planet is seven years up in the Endurance spacecraft that orbits the planet. This, too, is based in science, with Thorne including his calculations in the book "The Science of Interstellar." According to the physicist, Nolan actually requested a scientific explanation that would allow him to depict such a time dilation, prompting Thorne to carry out the relevant calculations. The physicist claimed to have been "amazed" to find that it was actually possible for a planet to be as close to a black hole as the film required without that planet falling into the black hole itself — that is, if the black hole spins at a certain speed. This also allowed him to justify the extreme time dilation on MIller's Planet, which is so close to Gargantua that the black hole's gravity distortions create the time differences between the planet's surface and it's orbit. But what about that black hole itself?

Interstellar correctly predicted the appearance of a black hole

If you needed any more convincing that "Interstellar" is one of the most scientifically accurate sci-fi movies ever made, how about the fact that Christopher Nolan and Kip Thorne accurately rendered the appearance of a black hole without ever having seen one. "Interstellar" correctly predicted the look of a black hole with Gargantua, the giant cosmic object into which Coop ventures during the ending of "Interstellar." In 2019, five years after the film debuted, the New York Times published the first-ever image of a black hole, and it looked remarkably similar to the one based on Kip Thorne's predictions from the film. In fact, as Nolan recalled in a recent featurette, the director actually called Thorne after the picture was released, saying, "It's a good thing you were right."

Certain liberties were taken when it came to Coop's trip into the black hole, however. While these cosmic objects remain largely mysterious (the closest to our planet is roughly 1,500 light-years away), we do have a pretty good idea of what might happen should a human attempt to cross the threshold — known as the event horizon — of a black hole. With stellar-mass black holes, a human being would be almost immediately spaghettified, a process that involves being stretched out due to a difference in the gravitational force between your head and feet. But in supermassive black holes, like Gargantua, scientists think that spaghettification would not happen immediately, and that an individual could theoretically cross the event horizon. Would there be a tesseract inside with Matthew McConaughey floating around? Almost certainly not. But since nobody really knows what the inside of a black hole would be like, there's always a possibility...

These are just some of the things that make the commitment to scientific authenticity in "Interstellar" clear. Also of note are the cylindrical spacecraft used to transport humans across the galaxy, which were based on physicist Gerard K O'Neill's actual designs. Though recent research has suggested the depiction of a wormhole in "Interstellar" isn't entirely accurate, for the most part the film uses real science to render some of its most seemingly fantastical elements.