15 Best Movies Like The Big Short

As the United States inches closer and closer toward a tipping point into class warfare, we can't help but think back to "The Big Short." Based on the nonfiction book of the same name by Michael Lewis, Adam McKay's irreverent spin on the events leading up to the 2008 financial crisis was already a much-needed wake up call for the culture when it premiered at AFI Fest in 2015. Now, nearly a decade later, it remains an incisive interrogation of the corporate corruption we see screwing over average consumers every day. Though finance bio-dramas are far from novel, McKay's film stands out as fuel to a fire of postmodern disillusionment that many films have since tried replicating without precisely duplicating.

In commemoration of its upcoming 10th anniversary, here are 15 more films that will help deepen your appreciation for McKay's darkly comic cautionary tale, from further investigations into the 2008 recession to other madcap stories of financial falls from grace.

Dumb Money

Reddit stock trading community r/WallStreetBets made a splash in 2021 when they successfully short-squeezed a group of billion-dollar hedge funds out of betting against GameStop's previously plummeting market value. As the meme lords made the front page, easy comparisons were made to the events of "The Big Short," in which its ensemble of outsiders similarly short the housing market. Just two years later, Hollywood dramatized the events of the GameStop short squeeze into "Dumb Money," another crass finance comedy that — in a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy — also saw comparisons to "The Big Short."

In reality, the events of "Dumb Money" and "The Big Short" are inverses of each other. The former explores ordinary people short squeezing from the outside in, while the latter follows folks within Wall Street shorting from the inside out. Nevertheless, they are both modern "David and Goliath" sagas propped up by star-studded ensemble casts and the same core message: eat the rich. Plus, as a fun fact, their histories coincidentally share a key figure: Dr. Michael Burry, portrayed by Christian Bale in "The Big Short," was an investor in GameStop who helped signal the stock as undervalued in 2019, two years before the squeeze.

The Wolf of Wall Street

Though they are two vastly different films, it's impossible to separate "The Big Short" and Martin Scorsese's "The Wolf of Wall Street" as two seminal modern entries into the same niche subgenre: finance biopics centered on smarmy fourth wall-breakers and the unchecked greed of Wall Street. However, while McKay's film is set before the 2008 housing bubble, Scorsese's film covers the fascinating true story behind Jordan Belfort (Leonardo DiCaprio), a debaucherous stock broker whose illegal scheming and unabashed extravagance would eventually get him arrested for securities fraud and money laundering.

Both films feature big stars, tons of needle drops, and a mix of both electric comedy and incredulous historical recount. That said, Scorsese's unhinged excess is at a scale that makes McKay's film look like child's play. This is by no means derogatory; "The Big Short" intentionally grounds and de-glamorizes its story, while "The Wolf of Wall Street" blows it up to incredulous proportions. McKay implicates his audience in cheeky ways, but Scorsese's Rorschach test in moral ambiguity sneakily asks audiences to examine why such horrible behavior makes for such glorious entertainment.

Inside Job

For those who still felt a bit lost on certain financial concepts after watching "The Big Short" (even Selena Gomez can't quite articulate synthetic CEOs in less than 3 minutes), "Inside Job" is the perfect follow-up. Directed by Charles Ferguson, this deep-dive documentary also chronicles the events that led up to the 2008 financial crisis but in far more detail, including the nitty-gritty on the history behind previous market crashes and how they paved the way for investment groups to scheme and have its many regulations gradually removed, allowing them to conflate the housing market whilst simultaneously betting against it. Ferguson's damning and unsubtle work came just two years after the crisis and deeply resonated with people, earning the Oscar for Best Documentary Feature in 2011.

Ferguson's doc is the exact antithesis of McKay's winking and nudging. However, its thorough examination of institutional corruption would likely get his endorsement. Just don't expect Margot Robbie to explain anything to you while naked in a bathtub.

Margin Call

On the surface, it's easy to recommend "Margin Call" as a follow-up to "The Big Short." Both films are star-studded prestige dramas about finance professionals in the lead-up to the fallout of the 2008 crisis. However, when looking more closely, "Margin Call" feels like the exact kind of film Adam McKay sought to poke fun at.

J. C. Chandor's film follows a group of employees at an unnamed investment bank who discover the market's volatility could bankrupt them. The drama is based in all kinds of jargon that never clearly conveys its own stakes despite popular celebrities (Zachary Quinto, Paul Bettany, pre-cancellation Kevin Spacey) conveying them. The film's humorless script and steely cinematography portrays the woes of rich a-holes as life or death. It even attempts to humanize several characters when we know they aren't the ones getting screwed. For those who enjoy watching Wall Streeters squirm, this will surely fit the bill, but it is perhaps even more valuable as a precursor to the kind of genre disruption McKay achieved through his take on similar events.

24 Hour Party People

In multiple interviews about "The Big Short," Adam McKay has cited Michael Winterbottom's "24 Hour Party People" as an inspiration for his film's formal playfulness. He even asked editor Hank Corwin, who went on to be Oscar-nominated for his work in "The Big Short," to watch the film before post-production began.

"24 Hour Party People" chronicles the rise and fall of Factory Records, a leading voice in Manchester's punk rock wave between the late '70s and early '90s. Though it tackles vastly different subject matter, McKay was inspired to lift several of the film's stylistic trademarks, from its unpolished camerawork to its frequent incorporation of real-life footage. However, the most obvious comparison is both films' frequent breaking of the fourth wall.

At multiple points in "24 Hour Party People," lead subject and narrator Tony Wilson (Steve Coogan) will openly address the audience in hilarious fashion, cheekily undercutting the film's themes while confirming whether or not certain events in the film actually happened. He makes Ryan Gosling's snide comments feel subtle by comparison.

Vice

After "The Big Short" transformed him into a prestige filmmaker overnight, Adam McKay set his sights on another American tragedy: the Vice Presidency of Dick Cheney. The resulting film, "Vice," was critically divisive and financially unsuccessful. However, it appeared to be more popular within the industry; it was nominated for eight Oscars versus five for "The Big Short" and even won Christian Bale a Golden Globe, something "Short" couldn't muster.

Though some would argue McKay takes political potshots in attempting to replicate his style of satire on an already heavily divisive figure, there's no denying that "Vice" further develops McKay's directorial voice into something more polished and patient. His ability to inspire even the slightest bit of sympathy for Cheney using more traditional filmmaking techniques is a mature step up from the crassness of "The Big Short," though don't let that fool you; McKay's cynicism and wit are in strong supply, pulling no punches on the harrowing corruption behind one of the most fraught periods in American political history.

Wall Street and Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps

There is no Wall Street film series more seminal than...well, "Wall Street." Oliver Stone's duology is a perfect starting point for anyone interested in the cinema of FiDi. However, those approaching it from the perspective of "The Big Short" will find its value twofold. The first "Wall Street" popularized the cinematic language we use to tell stock market stories today, while its 2010 sequel, subtitled "Money Never Sleeps," channels that same style into a story specifically set amidst the 2008 crisis. Michael Douglas' Gordon Gekko, in particular, is the archetypal fraudster by which characters like Ryan Gosling's Jared Vennett were surely inspired. His famous line, "greed for lack of a better word, is good," was even inspired by an actual Wall Street criminal.

Before social media radicalized an entire generation to scoff at the 1%, the "Wall Street" films told the stories of Bud Fox (Charlie Sheen), Gordon Gekko (Michael Douglas), and Jake Moore (Shia LaBeouf) with as much sincerity as any other high-stakes drama. "The Big Short" makes it fun to make fun of brokers' petty grievances, but watching "Wall Street" would have you believe there is still redemption and justice to be found in such a corrupt system.

Capitalism: A Love Story

Though "The Big Short" is primarily a story about the American economy, its final moments unfurl as a much larger statement on class disparity in America and the woes of capitalism. It's so infuriating that it might just radicalize you into hating the dreaded C-word (no, the other one), and who better to aid in said radicalization than documentarian Michael Moore? He is one of film's premiere voices in tearing through the establishment by exploring the corruption behind controversial events, from his Oscar-winning "Bowling for Columbine" to his financial smash hit "Fahrenheit 9/11."

His take on the 2008 crisis, "Capitalism: A Love Story" follows suit, breaking down the recession, its fallout, and the broader pitfalls of, as Moore calls it, "runaway greed." Fans of McKay's sardonic sense of humor will appreciate Moore's similar directorial style, including a heavy use of first-person narration and collage-like archival footage. However, the cheeky fabrication you get in "The Big Short" is nowhere to be found here; Moore's doc is all real people with real struggles, making his manifesto all the more damning.

21

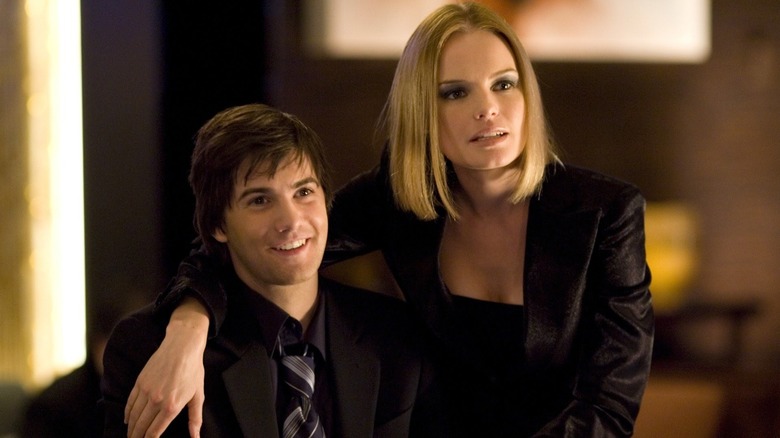

Wall Street isn't the only industry that can be gamed. Casinos are maybe the only gamble worse than the stock market, which means a cunning group of misfits could find a loophole. Thankfully, a group of MIT students and alumni did just that, inspiring the best-selling book "Bringing Down The House," which recounts their experience card-counting to bankrupt casinos all over the world. Similarly to "The Big Short," this book inspired a starry film adaptation, "21," directed by Robert Luketic and produced by Kevin Spacey (again, pre-cancellation).

The film tells the story through the eyes of student Ben Campbell (Jim Sturgess), an aspiring medical student invited to join the team after its leader, Micky (Spacey), notices his prodigal math skills. He is initially hesitant to join and only does so he can get money for tuition, but he winds up allured into the lifestyle to the detriment of his ambitions. Though Robert Luketic's heist thriller is more traditional than McKay's film, it is just as engaging of a drama and similarly critical of the American mindset and corrupt institutions that drive greed and commerce.

Thank You For Smoking

Jason Reitman's often overlooked directorial debut, "Thank You for Smoking," is one of cinema's sharpest takedowns of corporate rhetoric, government bureaucracy, and the modern media landscape, falling right in line with McKay's taste in political satire. The film follows Nick Naylor (Aaron Eckhardt), a spokesperson for big tobacco who is employed to vouch for cigarettes. When a congressman attempts to write defamatory cigarette packaging into law, Naylor's personal convictions and career interests come head-to-head.

Both "Thank You For Smoking" and "The Big Short" explore institutional greed with a biting comedic edge, complete with smarmy narration and a handful of hilarious cutaway gags. However, Reitman explores a number of McKay's ideas more explicitly. McKay may implicate the American government, but Reitman makes them a central character in the form of Senator Ortolan Finistirre (William H. Macy), a seemingly moral but secretly corrupt official with an axe to grind against Naylor. His inclusion illustrates that all institutions can be self-interested and disingenuous, even those that appear to have our best interests at heart. Both films also flip the script on the audience by the end, asking them to consider their own complicity, but Naylor's final speech is a specifically stirring call for the audience to not let the media dictate their own decisions.

BlackBerry

If "The Big Short" was mixed with "The Social Network" by way of "Silicon Valley," you'd get something resembling "BlackBerry," Matt Johnson's hilarious and heartbreaking examination on the rise and fall of the eponymous cell phone. Before the iPhone's algorithms gave us all mental illness, two humble programmers — Mike Lazaridis and Doug Fregin, portrayed by Jay Baruchel and Johnson respectively — envisioned a world in which folks could simply hold a computer in their hand. With the help of the wildly ambitious and wildly rageful investor Jim Balsillie (a scene-stealing Glenn Howerton), their company becomes internationally renowned, but narcissism and desperation lead to their downfall.

Both McKay and Johnson employ similar stylistic techniques throughout their films that could best be described as cinematically punk rock. The films' erratic handheld camerawork make you feel like a fly-on-the-wall behind closed doors, while its razor-sharp writing and assured performances give that voyeuristic appeal an adrenaline shot. Add some head-banging needle drops, a broad ensemble cast, and strong mid-2000s period detail, and you have a thoroughly engrossing double feature that pairs an Oscar winner with a comparatively underrated gem.

The Apprentice

The last thing most of us want is to dedicate more space in our brain to the inescapable presence of Donald Trump. However, much like "The Big Short" asks us to introspect on how we got to where we are now, Ali Abbasi's "The Apprentice" forces us to understand how men like Trump are made. Starring Sebastian Stan in an Oscar-nominated performance as Trump, the tell-all explores his rise as a real estate magnate under the tutelage of ruthless lawyer Roy Cohn (Jeremy Strong, also Oscar-nominated), as well as his tumultuous marriage to Ivana Trump (Maria Bakalova).

Both McKay and Abbasi are interested in how American capitalist institutions are fueled by a complete lack of empathy. "The Big Short" explores this through a variety of minor characters, from big bank figureheads to punchable real estate brokers, but we experience most of it from more balanced characters. In "The Apprentice," our main character is this advantageous self-absorption personified. We witness the nitty-gritty of how Trump crushed his own emotional vulnerability in service of wealth and power, which wrought devastating consequences for New York City and, eventually, the entire world. It's no surprise Donald Trump lambasted the movie and Sebastian Stan's performance — it's the story he doesn't want you, or America, to remember.

Pain & Gain

Michael Bay and Adam McKay seem like polar opposites nowadays; the latter used his comedy cache to invest in intellectual satire while the former cranks out action spectacles with little on their mind. However, one film in Bay's filmography stands out as common ground: "Pain & Gain," a surprisingly salient takedown of capitalistic ambition that, like "The Big Short," is also inspired by real life events. The film follows three bodybuilders who kidnap and extort a wealthy businessman in hopes of getting rich quick. Things, naturally, don't go according to plan.

"Pain & Gain" similarly utilizes comedic narration and speedily edited footage to create a distinct energy, but "The Big Short" looks meek in comparison to the grit and grime of Bay's vision: sun-drenched sweat, bold colors, down and dirty camerawork, and an unfiltered political incorrectness that reveals the many vices that human beings used to shield them from their own doubts and inaccuracies. The film's jabs at modern machismo are particularly biting; The Rock has always looked buff, but here he looks so roided out that it feels unnatural.

Moneyball

Author Michael Lewis is no stranger to film adaptation. In 2006, his book "The Blind Side" was made into the well-known 2009 film starring Sandra Bullock. Then, in 2011, another one of his books, "Moneyball," was adapted by writers Aaron Sorkin and Steven Zaillian. Between the two, "Moneyball" is the better spiritual sibling to "The Big Short," and it's not just because the subject of "The Blind Side" alleged the film is based on a lie. Yikes.

"Moneyball" also breaks down financial jargon in a snappy way, retelling the story of how the Oakland Athletics baseball team, and specifically coach Billy Beane (Brad Pitt, an actor who is also featured in "The Big Short"), used mathematical formulas to find undervalued players and save money on buying their team. It never musters the same fervor as McKay's sharp satire, instead leaning on more subdued and personal drama surrounding Beane's underdog journey, flashbacks to his regretful baseball career, and his relationship with his daughter after a quiet divorce.

Trading Places

"The Big Short" is a story about outsiders proving Wall Street wrong and no other movie embraces that same spirit more than John Landis' "Trading Places." The film begins with a chance encounter between spoiled commodities trader Louis Winthorpe III (Dan Aykroyd) and sly but unhoused con man Billy Ray Valentine (Eddie Murphy). After witnessing the incident, Winthorpe's bosses, the Duke brothers (Ralph Bellamy and Don Ameche), scheme to have them swap lives in an effort to see if either one of them can succeed in the other's circumstances.

Though some of its offensive humor doesn't hold up by today's standards, "Trading Places" is still a hilarious romp that sees a fun cast of characters stick it to narcissistic elites by beating them at their own game. Watching Eddie Murphy's charisma infiltrate the snootiness of investment banking whilst playing opposite Aykroyd's straight man is a novel comic approach, while Jamie Lee Curtis gives one of her most underrated performances as Ophelia, a sex worker who initially helps Winthorpe for his money but slowly falls for him. The film's stock exchange-set climax is one for the books.