The Real Reason Marvel's Daredevil And DC's Batman Are So Similar, Explained

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Who is the Marvel Comics equivalent to Batman? Is it Iron Man, another industrialist with no superpowers but plenty of resources, who fights crime with his own genius and inventions? Is it Moon Knight, another driven caped crusader? What about more direct Batman analogues, like Nighthawk? All valid answers, but for me, the closest Marvel has to Batman is Matt Murdock/Daredevil — and not just because Ben Affleck has played both Batman and Daredevil on screen.

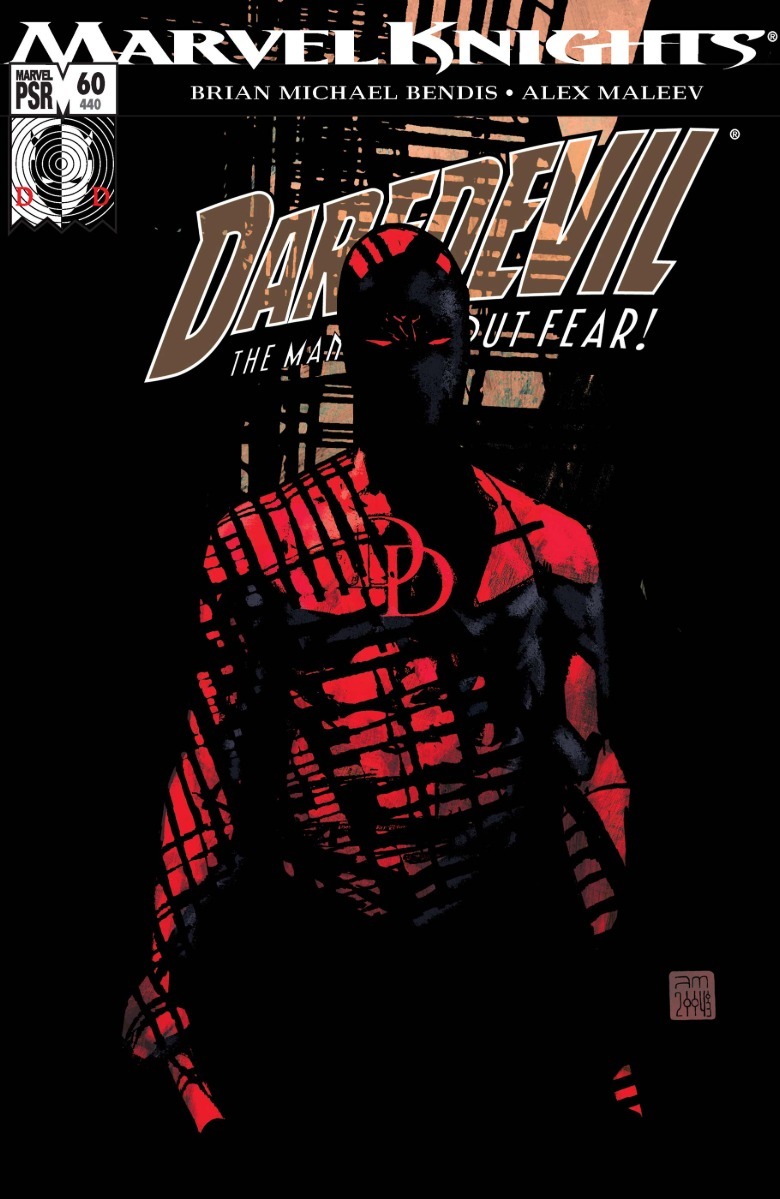

They're both broody and grim avengers of the night, who hand out justice with a hard bloody fist — fighting half like a boxer, half like a ninja — yet restrain themselves from killing. At night both Batman and Daredevil patrol rooftops and alleys, all part of their obsessive quests to be the savior of their city. Daredevil's horns give him a similar silhouette as Batman's cowl, and some artists draw Daredevil as blending into the shadows the same way the Dark Knight does (e.g. Alex Maleev, see below).

There are differences, and those unique qualities are what make Daredevil compelling. Most obviously, Daredevil is blind and that disability is also the source of his superpowers (enhanced senses, down to "radar vision" close enough to true sight).

Compared to the patrician Bruce Wayne, Matt Murdock's roots are much more working class. Hell's Kitchen has been gentrified today, but for most of its history it was home to poor Irish-American immigrants and/or their descendants. Matt Murdock is a lawyer because his father, an uneducated boxer named Jack, pushed him to be a professional so he could have a better life.

Batman has no faith in a higher power ("The world only makes sense when you force it to"), while Daredevil is religious — a Catholic boy who still dresses like his faith's symbol of evil. Daredevil's Catholicism means guilt hits the two heroes differently; they're both hard on themselves, but Batman rarely doubts himself the way Daredevil so consistently does.

So look beneath their masks and you'll find differences. On the surface, though, they mirror each other, and the stories they star in are often more "gritty" than their respective publishers' usual oeuvre. Why? It goes back to a single writer who wrote both characters: Frank Miller.

Frank Miller changed Daredevil, and then Batman, forever

Miller stands in a patheon with Jack Kirby, Alan Moore, Will Eisner, and Art Spiegelman; comic creators that didn't just work in the medium, but reshaped it. Miller did that, at first, thanks to Batman and Daredevil. In the late 1970s, Miller was a minor artist at Marvel when he lobbied for and got the job drawing "Daredevil," starting from issue #158. Remembering the experience, Miller wrote in 2000:

"I wanted the job. Boy, did I want that job. I'd always been intrigued by the notion of a hero whose defining attribute is a disability — a blind protagonist in a purely visual medium — and, most importantly, 'Daredevil' offered up a chance to draw the kind of spooky crime comics I'd always wanted to do."

After several issues of drawing "Daredevil," Miller asked his editor Dennis O'Neil for the chance to write a story. O'Neil, seeing nothing to lose, said yes. Miller turned that assignment into a full-time job writing and drawing "Daredevil." (Several of Miller's later issues were drawn by his inker, Klaus Janson, and "Daredevil" collections mention both of them.) O'Neil recalled in an interview years later:

"Frank asked if he could write a short backup story and, thinking that if he bombed I could always do an overnight rewrite, I said sure. He did well and I decided to chance letting him script the monthly book."

You can feel the jump in quality when the book becomes all Miller's. Miller's big influences were film noir and action manga, and you can see that by his two major additions: introducing ninja assassin Elektra Natchios as Matt's former lover, now foe, and bringing in Wilson Fisk/The Kingpin as the book's main villain.

Adopting a noir tone gave "Daredevil" a stronger identity, as Miller made the comic's narration text boxes less flowery Stan Lee, and more hard-boiled and staccato, like a Raymond Chandler PI character:

"My name is Matt Murdock. I was blinded by radiation. My remaining senses function with superhuman sharpness. I live in Hell's Kitchen and do my best to keep it clean. That's all you need to know."

Even Miller's art came into its own because he was able to write scenes that played to his strength, which he burned with enthusiasm to draw.

Miller left "Daredevil" after #191, but he returned soon after for a finale arc, "Born Again" (drawn by David Mazzucchelli, who had been drawing some "Daredevil" issues, mostly written by O'Neil, after Miller left the book). This story canonized Matt Murdock as a Catholic; not just as a background biographic detail, but a cornerstone of his character. Note how the issue titles all come from or evoke the Bible:

-

#227: "Apocalypse"

-

#228: "Purgatory"

-

#229: "Pariah"

-

#230: "Born Again" (which became the whole storyline's name)

-

#231: "Saved"

-

#232: "God and Country" (featuring Nuke, an insane patriot)

-

#233: "Armageddon" (a circular title, for it comes back to idea of the end of the world)

Frank Miller's Batman set a new standard

Daredevil made Miller into a comics superstar — enough that he found work at Marvel's distinguished competition, writing and drawing the samurai cyberpunk series "Ronin." Then, DC editor Dick Giordano recruited him to write a Batman story.

While he put blood, sweat, and ink into "Daredevil," Batman was in a different league for Miller; a childhood favorite, and a character he'd long wanted to tackle. But, as he told Nerdist in 2016, the idea of actually writing Batman at first seemed too daunting. Then, he turned 29 — the same age as Bruce Wayne — and realized he would soon be older than Batman. Inspiration struck:

"The more this year went on the more it bothered me that I might be older than [Batman]. So finally I [decided] to fix that, and make him older than me once and for all. So I conceived of a story where Batman was at the impossibly old age of 50."

"The Dark Knight Returns" (written and drawn by Miller, colored by his then-wife Lynn Varley) is the definitive "dark Batman" text. The comic, and the soon-to-come Batman movies that followed its path, removed the idea of Adam West as the public's accepted Batman, exactly as Miller intended. In a 2024 conversation with "Batman v Superman" director Zack Snyder at Inverse, Miller said of the old 1960s "Batman" show:

"It was basically a snide take on stuff that I remember that I absolutely loved. I loved the comic book characters and the TV show was constantly telling you how stupid the comic book was [...] I basically was just looking to get rid of all the sh*t and restore [Batman] to the kind of stature he had in my mind when I was seven years old."

Miller's Batman was Dirty Harry in a cowl, a crimefighter that truly inspired fear. If terror didn't work, violence would. The book inferred that Robin had died in action (and later Batman comics would follow), cementing that Batman's crusade truly is a war (and that his dedication to it makes him as crazy as his enemies). "The Dark Knight Returns" was also the first to suggest that the Joker's obsession with Batman is lustful — his last clash with Batman is in a tunnel of love at the Gotham fairgrounds. In the book's first chapter, Batman wields a sniper rifle to fire a grappling hook.

This feels like the genesis of Batman's grapple gun, first introduced in Tim Burton's 1989 "Batman" film and which nowadays is the Dark Knight's signature tool.

Miller approached Daredevil and Batman in similar ways, and his work on both fed into each other. His experience writing "Daredevil" prepared him to write Batman, then he came back for "Born Again" and worked on "The Dark Knight Returns" simultaneously. Working with Mazzucchelli on "Daredevil" then led to them teaming up once again for "Batman: Year One" in 1987.

Daredevil was originally inspired by Spider-Man

A lot of what fans consider essential to Daredevil (Elektra, Kingpin as the main villain, ninjas, Catholic guilt and self-righteousness, "Matt Murdock must suffer") comes from Miller. Some of the seeds are there from issue #1, like the inner conflict between Daredevil, a lawyer, taking the law into his own hands, and whether he's disappointing his father by following a life of violence. But they're barely explored; the ideas feel constrained by the formula of 1960s Marvel Comics. "Daredevil" never found a captivating identity as a book before Miller was writing it — 168th time's the charm, I guess.

Miller's "Daredevil" is so synonymous with the overall comic, and so influential on later writers, that it can be hard to understand what a sharp reinvention it was today.

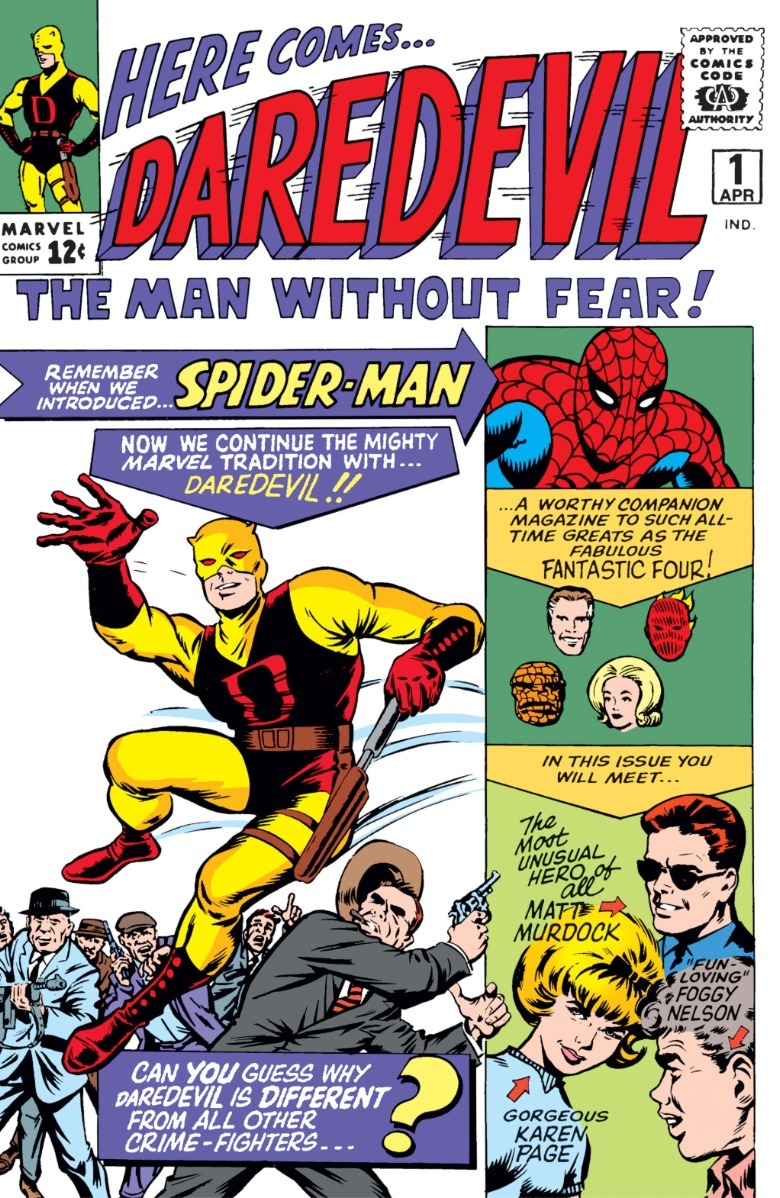

Early Daredevil wasn't a Batman counterpart, he was more like the low-rent Spider-Man. There's one reason that characters often team up, in comics and in film (Charlie Cox's Matt and Tom Holland's Peter, specifically). Take how Daredevil swings through Hell's Kitchen with his extended billy clubs, the same way that Spider-Man web slings through Manhattan. In "Daredevil" #1, our hero is quippy and plays cat and mouse with the gangsters who killed his father, like Spider-Man taunting Doc Ock. Later DD would just beat the hell out of them in a (truly) blind rage. The cover of "Daredevil" #1 cover outright compares him to Spider-Man.

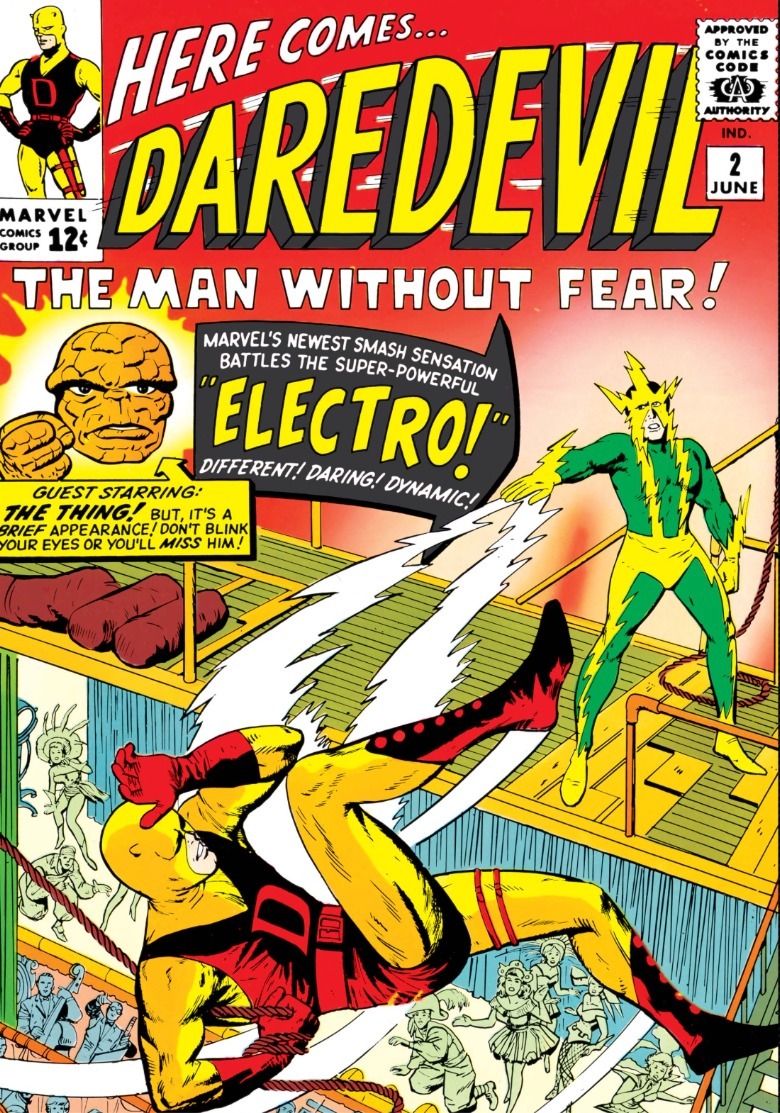

It's as if Lee wasn't confident enough in Daredevil to succeed as an idea on itself, or was stretched too thin to do anything but try and recapture lightning in a bottle. Supporting this, come "Daredevil" issue #2, the first super-villain he faces is Electro.

Even the Kingpin was originally a Spider-Man villain (and often still is). Since he was just a human crime boss, though, he fit the crime comic story Miller was telling. One can feel that Miller approached Daredevil as if it was the closest he'd ever get to writing Batman. (Just one more example: Elektra, and her love/hate dynamic with Matt, feels akin to Catwoman.)

Miller bound Daredevil and Batman together, and since you can tell similar stories with them, it's no surprise that many other writers have since worked on both comics. O'Neil, who originally succeeded Miller, had revitalized Batman comics back in the 1970s with artist Neal Adams. Brian Michael Bendis wrote the second best "Daredevil" run ever from 2001-2006 and then, like Miller, got to try his hand writing Batman over at DC (see: "Batman: Universe"). Bendis was succeeded as "Daredevil" writer by Ed Brubaker, modern master of noir and crime comics, who already had some Batman writing experience under his belt.

Most recently, Chip Zdarsky penned "Daredevil" from 2019 to 2023 and is about to finish up a run on "Batman" at DC.

Is Frank Miller's Batman the one we need -- and deserve?

In a further testament to Miller's influence, the upcoming television revival "Daredevil: Born Again" is named for his and Mazzucchelli's famous story. "The Dark Knight Returns" and "Year One" cast as long a shadow over Batman stories, but as beloved as they are, Miller's Batman work is generally more divisive than his "Daredevil" run. For everyone who loves Miller Batman, there's also those who feel future writers have fixated too much on those two stories over 80+ years' worth of others, or those who feel gritty Batman is too constraining for an inherently fantastical character and world.

In 2025, do we still need Frank Miller's Batman? One comic that says we do is the currently running "Absolute Batman" by writer Scott Snyder and primarily drawn by artist Nick Dragotta.

Dragotta's bulky Batman looks most like Miller's. As critics have picked up on and the book's creators have admitted, the story is consciously evoking "The Dark Knight Returns" — Gotham City is overrun with violence, and seemingly no-one can or will stop it, so Batman steps up. The fourth and latest issue of "Absolute Batman" (drawn by Gabriel Hernández Walta) pauses the ongoing story to flash back to how this Bruce, so different from the one we know, created his Batman identity. His trials and error in vigilantism is like a condensed version of "Year One."

"Absolute Batman" #4 is all about Batman, and I don't just mean the specific version of Bruce Wayne starring in it. The issue explores Batman's versatility as a character, and how different iterations should respond to the needs of the moment. Bruce putting together his crime-fighting persona, juxtaposed with flashbacks to his childhood self fine-tuning an engineering project for a school contest, reflects Snyder and Dragotta piecing together how this "Absolute" Batman should fit into the tapestry without disappearing within it.

One big change "Absolute Batman" made from the beginning is the origin story; this Bruce Wayne didn't lose his parents in a mugging, his father was a teacher killed in a mass shooting. Speaking to Polygon, Snyder revealed a key event from his own life that's been shaping his Batman writing for a decade, including now in "Absolute."

"[My son] went to school one day when he was in first grade, they didn't realize he was out in the hallway when they did an active shooter drill. And it was just a drill, but he was terrified. He got locked out in the hallway. From that day forward all year, he wouldn't go to school without a thermos; he would never use the bathroom at school [...] It just made me very aware of the fact that I grew up with a Batman in 'Dark Knight Returns' and 'Year One' that I was so excited to see. And those kinds of books go up against the things that felt real to me as challenges and fears in New York City, and in the world, the Cold War."

Snyder's Batman work is him very consciously trying to mold a Batman who addresses the anxieties his kids see and feel in the real world. So, he endows the "Absolute" Batman with the now all-too common generational trauma of school shootings. While the Frank Miller Batman comics did revel in Batman brutalizing street thugs, they always acknowledged more systematic issues too, and featured a Batman unafraid to confront them. (See the page from "Year One" below.)

"Absolute Batman" #4 concludes that, even almost 40 years later, we still need a Batman as fearless as Miller's — "The Man Without Fear" may be Daredevil's official nickname, but Batman earns it too.