One Of Captain America's Best Villains Was A Former US President

Captain America first debuted in Jack Kirby and Joe Simon's "Captain America Comics" #1. Hitting newsstands at the tail end of 1940, the comic's cover page showed its flag-draped hero punching out Adolf Hitler.

Since then, most of Captain America's enduring enemies have been fictional Nazis, from the Red Skull to Baron Zemo. But not all fascists come from Germany. The U.S. has spent the last decade getting that rude awakening over and over, and stubbornly refusing to listen, but it's one that Captain America heard much earlier, and heeded, back in 1974. Yes, Captain America was coated in the grey morals of the real world long before the movies.

The "Secret Empire" storyline ("Captain America" #169-175), written by Steve Englehart and drawn by Sal Buscema, features the titular conspiracy out to discredit Captain America and seize control of the American government. The Secret Empire wear purple and black hooded cloaks, and address themselves only by numbers, concealing their identities.

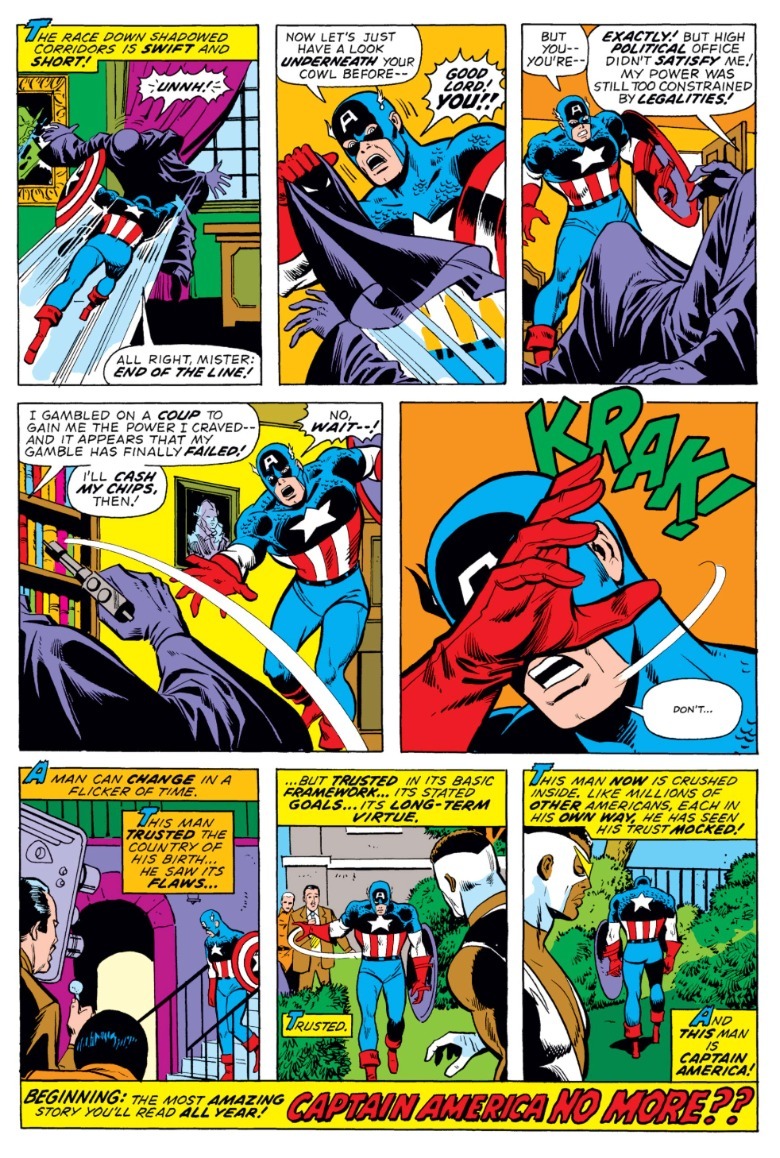

In issue #175, Cap and friends defeat the Secret Empire on the front lawn of the White House. All appears well until the Secret Empire's leader, Number One, bolts for it. Cap confronts and unmasks him inside the White House, leaving his jaw on the floor as the villain takes his own life.

Steve is so shaken that, in #176, he resigns as Captain America and eventually takes on a new superhero identity: Nomad, the man without a country. He finally becomes Captain America again in #183, deciding that it's important he represent what America should be.

The issue does not show the reader Number One's face, nor does it give us him name. However, between how the truth destroys Cap's faith in America, the villain's dialogue that he wanted more power than the government could give him, the White House setting, and the story that was dominating the news back in 1974, there's one conclusion: the Secret Empire was led by President Richard "Tricky Dick" Nixon.

Marvel Comics retold Watergate as Secret Empire

In a 2017 interview with Newsarama on the legacy of his "Captain America" run, Englehart spoke of how "Secret Empire" was his response to the Watergate scandal. (If you don't know: during the 1972 election, Nixon had the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee at the Watergate hotel in Washington D.C. robbed and bugged. The discovery and cover-up eventually led to him resigning the presidency on August 9, 1974.)

Englehart described watching the Watergate scandal as being like, "a political thriller in real life, this sort of daily unfolding of the inner workings of this conspiracy." With the news dominating America, he decided that "there was no way Captain America could just keep fighting the Yellow Claw with that going on." So, he took the basic idea of a President running a conspiracy and Marvel-ed it up. ("A story about people breaking into a campaign office — that would make a pretty boring comic book")

The allusions to Watergate are there in "Secret Empire" before the ending. The arm of the Secret Empire trying to discredit Cap is called the Committee to Regain America's Principles (C.R.A.P.), just like Nixon's Committee to Re-Elect The President (C.R.E.E.P.) funded the Watergate scandal. C.R.A.P. is headed by an ad man named Harderman, a roman à clef for Nixon's chief of staff H. R. Haldeman.

As for that ending, Englehart wanted a shocking ending that would truly make Captain America reconsider himself, and one that would do justice to the pressure cooker of the real scandal. "Nixon didn't blow his brains out, but he destroyed his own career and that's political suicide," Englehart told Newsarama.

People of my generation, who have always lived under a government that does nothing but inspire pessimism and distrust, don't quite grasp what a shock Watergate was. But in Englehart's day, "there were statesmen on both sides of the aisle who were more concerned with the republic than any political party" and a media ecosystem that still valued journalistic objectivity.

Many artistic liberals of Englehart's generation channeled their frustrations with Nixon into their art. (George Lucas based the Empire of "Star Wars" on Nixon's America.) The disillusionment of Watergate also left the country in a prime position for Ronald Reagan to sucker it with his "Morning in America" schtick six years later.

Nowadays, lampooning Nixon as a national embarrassment is an American pastime, including in other comics like "Watchmen" and comedy films like 1999's "Dick." "Secret Empire" itself reads like that today, but there's an important detail.

"Captain America" #175 was published months before Nixon resigned, and in effect admitted his guilt for a pardon by then-President Gerald Ford — the same way Captain America first debuted punching out Hitler a year before the United States entered World War II. From the very beginning, Captain America has represented the wish that the U.S. will do the right thing and not the reality that it so rarely does. Englehart understood that's how you make Captain America into a long-lasting and resonant character.

Secret Empire is the most influential Captain America comic

Englehart wrote "Captain America" for about 30 issues, #153-167 then #169-186. (#168 was a fill-in penned by Roy Thomas and Tony Isabella.) It's not all great; Englehart's final issue, #186, infamously and embarrassingly reveals Sam Wilson/The Falcon was actually a Harlem pimp brainwashed by the Red Skull into teaming up with Cap. Looking at what came after, though, he's the single most influential Captain America writer besides Jack Kirby, Joe Simon, and Stan Lee. Ever since Englehart's 1970s run, there's been an understanding that Captain America — the comic and the character — should reflect the mood of the nation he's named for.

In that aforementioned Newsarama interview, Englehart said that when he got the job, "Captain America" wasn't a hit title. To turn it around, he read through the character's whole history and concluded he had outlasted his usefulness after WWII. That's why the attempt to carry Cap on into the 1950s as a "commie-smasher" failed and was dismissed when "Avengers" #4 reintroduced him in 1964 as a man out of time. For Cap to endure, he couldn't be a man of a long-past moment. Englehart explained:

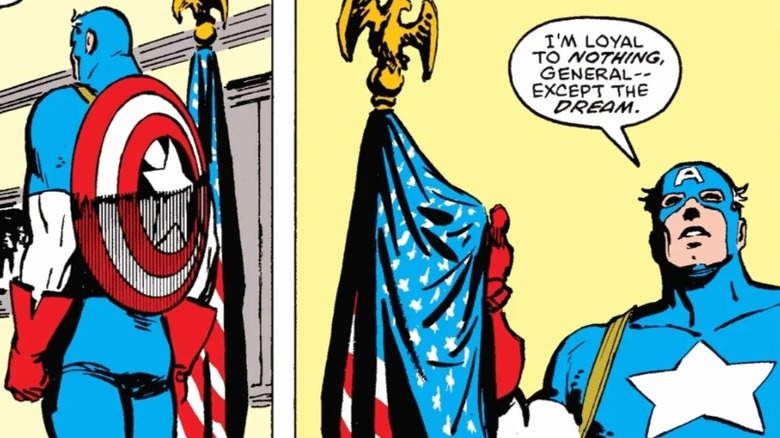

"At the time [the early 1970s] there was a very strong anti-war sentiment, so I looked at Captain America and said 'OK, here's a guy who is now tied to something that's completely unpopular.' I may not be a genius, but I figured maybe that's the problem. So I came up with this idea that he stood for general American ideals rather than any specific thing that had happened in our history."

The first story he wrote on "Captain America" in issues #153-156 retconned back in the more reactionary 1950s Cap. This Captain America, Englehart wrote, was an imposter (later named William Burnside). From the beginning, Englehart was putting the idealized Captain America in conflict with the realities of America. "Secret Empire" took this to the next level by directly drawing Cap into the politics of the time; his resolve in the American Dream needed to be tested to prove his usefulness as a character.

How later Captain America comics follow Secret Empire

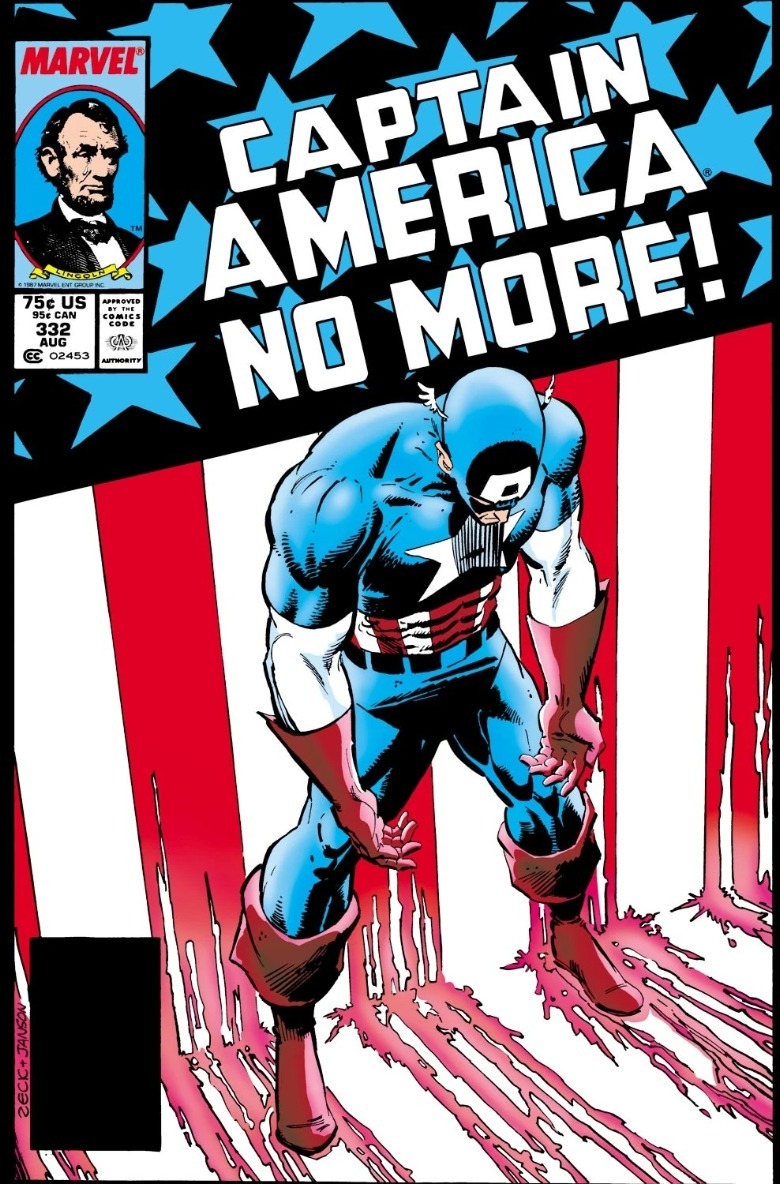

Many of the most famous "Captain America" comics feel like they exist in the shadow of "Secret Empire." Shortly after Englehart left, Kirby came back to write and draw "Captain America" for about 20 issues (#193-214). His first storyline, "Madbomb" was quite similar to "Secret Empire," featuring a multi-part story about a secret organization attempting to overthrow America. Mark Gruenwald's lengthy run on "Captain America" featured a storyline similar to Steve's time as Nomad; in 1987's "Captain America" #332, Steve resigns as Captain America because he refuses to be an official agent of the U.S. government. Cue the introduction of John Walker, a Captain America who follows orders without question, not the dream.

After 9/11, America was in a darker place, with the old national villains of the Cold War replaced with the War on Terror. To fit that mood, Ed Brubaker's exemplary run on "Captain America" in the 2000s turned the comic into a stale beer espionage thriller; still plenty pulpy, but less bam-pow. Brubaker's initial villain is Aleksander Lukin, a Russian KGB officer turned energy oligarch. Bucky, as the Winter Soldier, stands in for the lingering sins of the deposed Soviet regime.

The middle chunk of Brubaker's run saw the Red Skull assassinate Steve Rogers, leaving Bucky to take his place as Captain America. "The Death of Captain America" follows Bucky's struggle to live up to Steve's example, as the Skull plotted a legal coup via a puppet U.S. presidential candidate. When the comic was running in 2008, faith in the American Dream was at an all-time low due to the financial crisis and George Bush's administration being a cemented disaster. (Really, faith in that Dream has never recovered.) Brubaker killed the icon of America's self-image to see if it could be restored. Then in 2014, "Captain America: The Winter Soldier" the movie turned Steve into a skeptic of drone warfare and mass surveillance.

"Spider-Man: Life Story" by Chip Zdarsky and Mark Bagley shows what it would be like if the Marvel Universe moved in real time. (In this world, most of the heroes debut in the 1960s, because that's when they were first published, then keep aging in real time.) Unlike the Cap in the real comics of the 1960s, this one enters the Vietnam War against the Americans, having concluded the war is unjust and it's the people of Vietnam who need his mighty shield. Embodying the vaunted ideals of America can and should mean acting against what the people who rule the nation do.

Then on the other side, you have Mark Millar's Ultimate Captain America. He, like Brubaker's Cap, is a Captain America for the Bush years — one who embodies the dogma of that time, not the uncertainty. Ultimate Cap is one who never questions America, because for him, America by definition can never be wrong.

When Captain America said 'Hail Hydra'

"Captain America: Steve Rogers" #1 by writer Nick Spencer and artist Jesus Saiz. It's the most infamous Marvel comic published in recent history, entirely for its widely remembered and mocked final page. Captain America declares "Hail Hydra," saluting the Nazi-offshoot organization run by his greatest enemies. All this time, Cap has been a fascist in disguise?

Spencer's story culminated in a 2017 crossover event where the Hydra Cap seized control of America. The title of this story? "Secret Empire." Once Captain America stood in for his readers' shattered trust in the United States, now he takes advantage of it to destroy the nation's guiding principles.

Of course, this wasn't a permanent change. "Captain America: Steve Rogers" #2 instantly explained what had happened; using the reality-warping Cosmic Cube, the Red Skull rewrote history so that Steve Rogers had been raised as a HYDRA sleeper agent. In the finale of "Secret Empire," the original heroic Captain America emerges from the Cube's nether realm to do what he does best: punch a Nazi.

So no worries, Hydra Cap is not the real Captain America ... or is he? "Captain America: Steve Rogers" #1 debuted in May 2016, when Donald Trump was running a racist presidential campaign under the slogan of "Make America Great Again." Despite Spencer and Marvel's denials, turning an American icon into a smiling face hiding evil feels like a pointed choice. Or it would be, but the comic downplays Hydra's connections to the Nazis.

During Jonathan Hickman's "Secret Warriors," he revealed Hydra had actually been founded centuries ago in the Marvel Universe. Spencer takes that to suggest the organization originally followed a more "accepting" authoritarianism that only allied with Nazi Germany, which let the Red Skull "pervert" the "true" Hydra the new Captain America is loyal to. During Hydra's reign, Inhumans are put into concentration camps and mutants are exiled, but there's no references to any white supremacist policy.

Some of Spencer's intent is to show the seductive side of fascism, and how its followers don't see themselves as evil. Hydra Cap still has many of his original qualities, including his love for Sharon Carter and Bucky. He wants his superhero friends on his side, but understands them all well enough to realize that won't happen. If Hydra were to be overtly racist, then it would be harder for audiences to see its supposed positive qualities — but that just loops around to doing the fascists' work for them, selling their message as good!

Captain America is more than Steve Rogers

Now, "Steve Rogers" is just one half of Spencer's "Secret Empire" saga. He wrote "Captain America: Sam Wilson" in tandem, which even more baldly satirizes the hot-topic issues of 2015-2017; the first issue features Sam trying to save some Mexican migrants from a border patrol, and recurring villains in the run include a new private police force, the Americops, and Alex Jones type conspiracy streamer Harry Hauser.

In keeping with that, Spencer writes Sam as a transparent stand-in for President Barack Obama. On one hand, conservatives hate seeing a Black man in a position of authority and one where he represents America as a whole. So, they lead a "Take Back The Shield" campaign, calling Sam a socialist, anti-American, and all but accusing him of being born in Kenya. In turn, Sam spends all his energy trying to appease them, and only alienating those more naturally inclined to support him. "Captain America: Sam Wilson" issue #13 features the Black superhero Rage shouting up at Sam to do something about police brutality, and Sam just flies away indignant.

The solutions Sam offers only paper over bigger issues. When Sam confronts some greedy CEOs that allied with the Serpent Society, they counter that he can't arrest them because they control too much of the economy. Remove them, and the house of cards topples. Sam accepts they are indeed too big to fail — so he only arrests a single one, as a warning to the others to stay in line. That's one more punishment than Obama dealt out to the criminal bankers who crashed the housing market. When the Americops' victims pile up, Sam (using his empathetic connection to birds) sets up a surveillance network across NYC to ensure none of them step out of line. Naturally, this has nil effect. By the end of the run, Sam quits being Captain America (the cover homages "Captain America" #176) and feels most of the American people weren't even worthy of him trying to help them.

Spencer's "Captain America" exposes the limits of what American liberals deem "acceptable." Even though these comics often identify the right individual villains, they reject the idea we can or should change the system that propped these bad actors up.

Ta-Nehisi Coates' Captain America questioned the Dream

The next "Captain America" writer, journalist turned fiction author Ta-Nehisi Coates, built on both "Secret Empire" storylines for his 30-issue run. Running from 2018 to 2021, this "Captain America" run explores the United States under Donald Trump. Spencer's run, and people now disliking Cap for the actions of his doppelgänger, are a stand-in for the anger many Americans felt towards Trump and their own country for putting him into power. Like in Englehart's original "Secret Empire," Cap is ostracized after being framed for murder and must consider his own identity in a country that's changed so much from the one he first pledged allegiance to.

Unlike the previous writers discussed, Ta-Nehisi Coates is African-American. His experience is both central to his writing (from his non-fiction like "Between The World And Me" and "The Case for Reparations," to his first novel "The Water Dancer," which is about an enslaved Black man in the antebellum South who gains the power to free his kin) and means the lasting prejudices of American are something he's felt firsthand.

That's why under Coates' pen, Cap starts to question the Dream itself. Back in Englehart's "Secret Empire," Captain America muses the 1940s were a "simpler time," while in Coates' he finally recognizes the Allies may have been only a lesser evil than the Nazis; "a Jim Crow army" that made common cause with Stalin.

The first arc is titled "Winter in America," flipping Reagan's words to underline that America is in a dark hour, while following ones are titled "Captain of Nothing" and "The Legend of Steve," suggesting that Cap's strength comes from his heart, not the country itself. The overarching theme of Coates' "Captain America" is that no-one in America has faith in higher ideals anymore, leaving demagogues plenty of room to sweep in and lead the masses (especially young men) astray. The run ends, though, with Cap defeating the Red Skull by publicly exposing what the villain really thinks of his followers.

Part of the legacy of Watergate is the belief that the President can be held accountable or that if the press sheds sunlight of the truth on corruption, Americans will rally to hold their leaders accountable. During the first Trump administration, liberals desperately clung to this hope, but doing so now is delusional. America has re-elected Trump, and its justice system has dismissed any criminal cases against him.

Whoever writes "Captain America" over the next four years and beyond, they should remember Englehart's belief that the comic is one that should reflect the America of now — even and especially if that means moving beyond the lessons and ultimately optimistic conclusion of the original "Secret Empire." The history of America is still being written and there's no universal balance, or red, white, and blue superheroes, here to ensure the Dream wins the day.