The David Lynch Movie Every Single Child Should Watch

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

I had a fever. I was not well and could not think straight, but, being an age less than 10, I wasn't frightened. I'd been sick before and gotten better. My parents were unconcerned, the family dog was on the opposite end of the living room couch and the television dial was switched to The Movie Channel. While my friends were stuck in an overheated classroom learning cursive writing by rote like a pack of healthy suckers, I was drifting in and out of consciousness as films happened on the cathode ray tube nestled into a carved-out wooden nook eight feet away from me. I don't remember if I had a sore throat or a persistent cough. I do remember that I was happy and hungry for sensation. This was my happy place.

At this age, I'd watched enough movies to know that they weren't all going to be "Jaws" or "Airplane!" – which, to my young mind, represented the apex of cinema. I knew all about the Academy Awards, and kept tabs on which films were nominated for Oscars. I recall finding it strange in 1980 that two black-and-white movies were up for Best Picture, and being disinclined to watch them for this very reason. But on this sick day, the programmers at The Movie Channel had determined that I'd spend my afternoon watching David Lynch's "The Elephant Man."

I wasn't completely unreceptive to the idea. The grotesque makeup design by Christopher Tucker gave Lynch's film the allure of a monster movie. Since I'd watched most of Universal's 1930s and 1940s horror classics by this point, I could hang with a black-and-white movie if there was a hideous creature lurking within it. In effect, I approached "The Elephant Man" as a freak show. Two hours later, nursing a temperature north of 100-degrees, the world was a wholly different place.

The monsters of The Elephant Man are terrifyingly human

When I learned yesterday afternoon via a flood of texts that David Lynch had died, I felt unmoored from reality. Though the longtime smoker's recent disclosure of his emphysema diagnosis forced us to consider a world sans further surrealistic excursions from the sui generis filmmaker, I still couldn't get it in my head that an artist this vital and boundlessly inventive was mortal. Given that I was in the middle of writing an appreciation of the just-passed Bob Uecker, I didn't have the psychic space to adjust to this new reality. But before I plunged back into the sardonic brilliance of Uecker's Harry Doyle in "Major League," I gave myself a moment. And in that moment, as I fought back tears in the middle of a public library, I placed myself back on that couch, sick as a dog, watching "The Elephant Man."

It had been decades since I'd last watched "The Elephant Man," but I could still summon up the memory of that nightmarish opening sequence where John Merrick's mother is attacked by a herd of elephants. Was I supposed to regard this incident as responsible for Merrick's deformities? Lightly hallucinating myself, I was probably more befuddled than terrified; I do know that I'd never seen a studio movie pull anything this strange before, which bought my attention for at least another ten minutes.

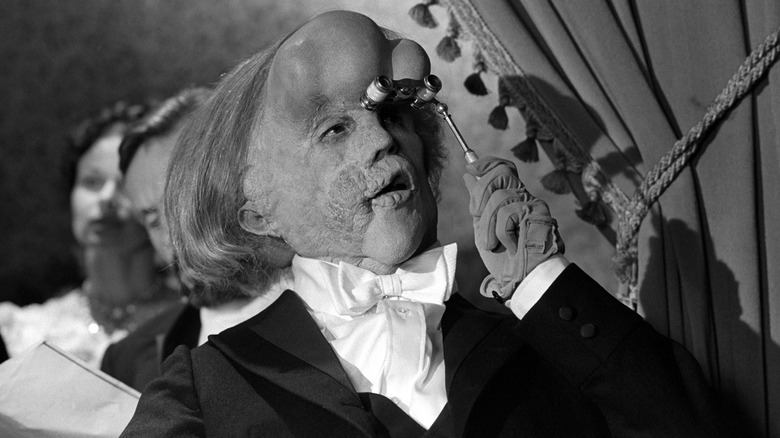

In the film's first conventionally staged scene, we're guided through a freak show from the perspective of Dr. Frederick Treves (Anthony Hopkins), who's curious to see why police officers have been called to shut down one of the exhibits. The ambitious surgeon learns that an attraction called The Elephant Man is the cause of the stir. When he learns that this creature is so malformed as to be considered indecent for public viewing, he returns later to pay the beast's owner handsomely for a private showing.

Lynch masterfully treats Treves' visit as a suspense set piece, with the handler leading the doctor through a dark corridor and into a room, which slowly comes aglow with firelight to reveal Merrick in all his unspeakable ugliness. Lynch pushes in on Hopkins, who, rather than gasp, sheds a tear. He is moved by the condition of this man, and, we presume, wants to help him.

The viewer doesn't get a proper introduction to Merrick until a half-hour into the movie, by which point we've seen him put on display for the gawking edification of Treves' colleagues and exploited anew by a hospital orderly. After such a prolonged build-up, the Merrick we've imagined winds up being way more monstrous than the one whose appearance elicits a bloodcurdling scream from an unsuspecting nurse – at least, that's how it felt to me on that couch. From that moment forward, I was as riveted by "The Elephant Man" as I had been during the trench run finale of "Star Wars."

A child's primer to the unknown

I am not a parent, but I was a child once and I firmly believe that many kids can handle unsettling subject matter provided the director exercises restraint and compassion. Though Lynch does not shy away from the cruelty heaped upon Merrick (his kidnapped return to the freak show in the third act is particularly harrowing), the kindness he's shown, which allows him to come out of his shell and reveal himself to be a human being rife with potential, is what resonates long after the credits roll. On this basic level, "The Elephant Man" is ideal viewing for children.

What makes it essential is the Lynch of it all. The aforementioned prologue, Merrick's trip to the pantomime and his passage into the cosmos are wondrous and mysterious in equal measure. That he hastens his death by removing the pillows from his bed in the final scene might prompt some questions from astute young ones, but there's no better way to complete this Lynchian primer by responding, "I don't know." That's right, kids. It's up to you to figure it out, and, what's more, there's no wrong answer. When they ask if Merrick's gone to heaven, again, gently reply, "I don't know." And if you don't feel like fielding these questions, I have the perfect solution: let them watch it alone.

That's what I did on a winter afternoon 40-odd years ago, and it was this memory that soothed my soul as I took my first uncertain steps forward in a world where David Lynch is now a memory – one that will last forever because nothing will die.