The Best Part Of Wolf Man Recalls Director Leigh Whannell's Most Underrated Movie

Warning: This article discusses major spoilers for "Wolf Man."

Before Leigh Whannell took his talents to the Universal Monsters franchise for a double dip, the Australian filmmaker first plied his trade as an actor, a writer on the "Saw" and "Insidious" franchises, and (most importantly for our purposes here) a director who first made a name for himself with stylish, low-budget thrillers. His precise career trajectory has hardly been a typical one compared to most, but the broad strokes of working his way up the studio system until reaching his apex — thus far, at least — with "The Invisible Man" and most recently "Wolf Man" (which I reviewed for /Film here) couldn't have been more ideal. It's hard to miss how his latest monster movie feels like a culmination of almost every lesson learned in "The Invisible Man," particularly with its approach to making the title character feel fresh and modern. But more than anything else, "Wolf Man" echoes back to arguably Whannell's most underrated movie of all: "Upgrade."

The 2018 sci-fi flick instantly made waves upon release (you can check out /Film's glowing review by Matt Donato here) and inspired something of a cult following for its inventive camerawork, its genre-bending story, and the fact that it did Venom better than any of the actual "Venom" movies ever did. The film follows Logan Marshall-Green as Grey Trace, an old-school junker/mechanic who ends up implanted with a cutting-edge chip (and its accompanying artificial intelligence, STEM) that essentially turns him into a high-tech vigilante.

On the surface, neither "Wolf Man" nor "Upgrade" would seem to share much in common ... until you take a deeper look at how both treat the idea of perspective, autonomy, and the way we depict those concepts in film.

The best part of Wolf Man is more than just fancy filmmaking

It sounds dumb to say (type?) it out loud like this, but everything we see depicted in a movie or television show was done with considerable amounts of intentionality and purpose. Think of any closeup/insert shot of a hand holding a coffee mug or phone screen, an establishing shot showing us the skyline of a city or the exterior of a building, or the vast array of colors that make up the production design, costumes, and overall look of an entire movie. All of it was done for a specific reason — whether to evoke a particular emotion, communicate some key bit of information, or simply provide context for the rest of the scene.

So when it comes to what's almost certain to be the biggest and best talking point in "Wolf Man" (aside from all that controversy over the creature design), it's worth digging deeper into why Leigh Whannell decided to shoot those gnarly-looking scenes from the Wolf Man's perspective the way that he and director of photography Stefan Duscio did.

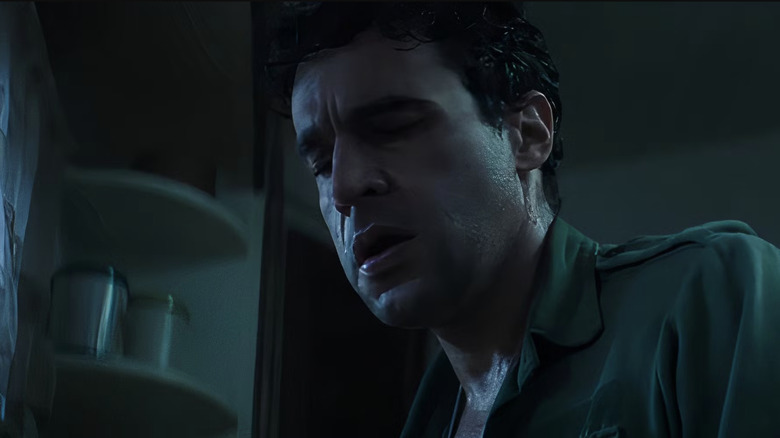

The first of these trippy moments comes after poor Blake (Christopher Abbott) has already been scratched by the Wolf Man during that tense car crash in the Oregon forest early on, and is now progressively succumbing to his symptoms. At first, we don't get a full picture of what's wrong. Sure, he seems a little sweaty and nervous, but otherwise seems capable enough of protecting his family. That is, until he's noisily boarding up the front door of the cabin, his wife Charlotte (Julia Garner) and daughter Ginger (Matilda Firth) wander into the hallway, and just ... stare at him blankly. It's not until a few scenes later that we discover that they're not the ones acting weird — he is. After locking audiences strictly in the point of view of Blake, the camera smoothly pans over to Charlotte's perspective and reveals the full extent of her husband's transformation into the Wolf Man. The lighting dramatically changes, the very framing of the camera literally tilts off its axis, and we realize that Blake's condition has already worsened significantly. He can't speak, his wounds have festered, and he's well on his way to becoming the Wolf Man.

How Wolf Man and Upgrade pull of similar tricks

In both "Upgrade" and "Wolf Man," Leigh Whannell's clever filmmaking decisions are using the conventions and our own expectations of the genre to keep viewers on their toes. "Upgrade" mostly relies on wildly jarring tilts and shots that ignore the usual horizons of a frame — all of which disorients us and help us buy into the hard-hitting action. (The moment Grey allows the AI in his head to fully take over his body and fight his battles for him, as seen in this clip, is the earliest and most effective example of this in the movie.) Although "Wolf Man" never opts for this maximized approach of controlled chaos, Whannell's similar choice to completely alter the visual language of the film accomplishes much the same effect.

In "Wolf Man," Whannell and director of photography Stefan Duscio reunite — yes, they also worked together on both "The Invisible Man" and "Upgrade," which should hardly come as a surprise — and work their unique magic all over again. In this case, they rely on a much more subdued method to put audiences back on their heels. After putting us exclusively in the headspace of Blake for the entire movie, where we rarely (if ever) see anything that he doesn't see himself, we suddenly change places as the camera quite literally glides over to Charlotte's perspective. This first occurs at Blake's bedside, and again in the darkened basement as she frantically calls for help on the CB radio ... though we initially see this in the night vision and with the muddled audio that Blake experiences in his sensory-overloaded state.

While this is a completely different shift in perspective than what the duo pulls off in "Upgrade," Whannell and Duscio find an equally as effective way to keep us unsettled during these moments in "Wolf Man," all while staying 100% faithful to the wildly different tones of each respective movie. The Leigh Whannell who made "Wolf Man" simply couldn't have done it without the Leigh Whannell who first wowed us with "Upgrade" — and we're lucky to have both.

"Wolf Man" is now playing in theaters.