The Landmark Sci-Fi Movie That H. G. Wells Hated

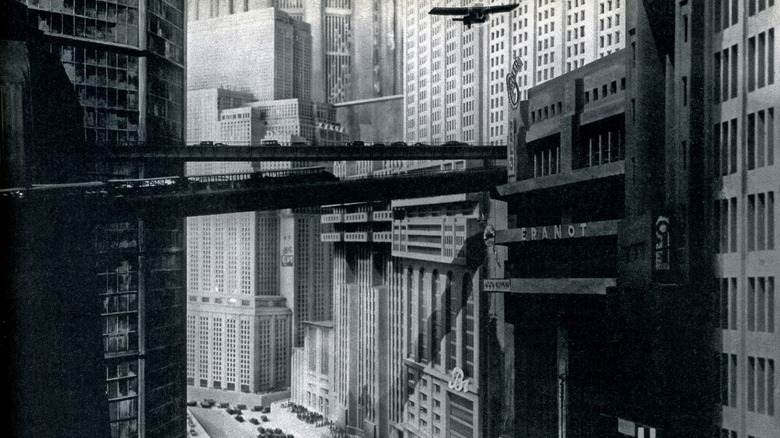

Fritz Lang's 1927 sci-fi epic "Metropolis" regularly appears on lists of the best movies of all time, and is certainly one of the most important works of science fiction ever produced. "Metropolis" takes place in an industrialized future where the world's wealthy live in meticulously constructed towers, and commute via fantastical blimps and flying machines. They engage in frivolous romantic misunderstandings, and enjoy lazing about in gardens eating rich foods. Meanwhile, under the city, impoverished laborers are literally working themselves to death to keep the machines running.

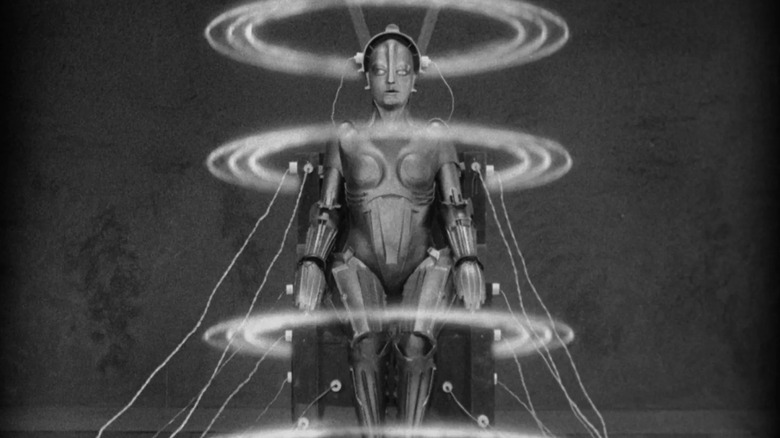

One of the city's most prominent rich brats is Freder (Gustav Fröhlich) who, by happenstance, witnesses a peaceful labor protest. He becomes instantly enamored of Maria (Brigitte Helm), the pacifist ruler of the movement, and becomes curious as to what the lives of laborers are actually like. He moves underground and sees the sweat, oil, and terror first had. The machines, he feels, are like a hungry evil god ("Moloch!") who eats people alive. Meanwhile, Freder's father (Alfred Abel) has been conspiring with a mad scientist (Rudolf Klein-Rogge) who aims to build a robot duplicate of Maria. The plan is to send the robot duplicate back into the underground, have her stage a violent uprising, and use the violence as an excuse to kill the working classes.

It's hardly subtle, but it's powerful. To this day, almost a century later, audiences are hypnotized by "Metropolis," and film school still have it on their syllabus.

But it wasn't always deeply beloved. Indeed, a deep dive into film reviews written in the late 1920s reveal a few critics who were put off by the film's mawkish melodrama and ultra-obvious messaging. Indeed, the 1927 New York Times review was a litany of complaints about its turgid storytelling and blunt politics.

And it was written by sci-fi master H.G. Wells, the author of "The Time Machine," "The Invisible Man," "The War of the Worlds" and "The Island of Dr. Moreau."

H.G. Wells haaaated Metropolis

It may be hard to read the scanned newspaper page on the New York Times website, so Wired has luckily transcribed the entire review. It begins with the sentences, "I have recently seen the silliest film. I do not believe it would be possible to make one sillier." Which ... yowch. Shots fired, Herbert. This may have been a mere blow to the ego had it come from any other critic, but Wells was already an established master, so it comes across as particularly harsh. The review is 2,880 words long, and every observation is a barb. Wells continued:

"It gives in one eddying concentration almost every possible foolishness, cliché, platitude, and muddlement about mechanical progress and progress in general served up with a sauce of sentimentality that is all its own."

Although he did admit that "Possibly I dislike this soupy whirlpool nonetheless because I find decaying fragments of my own juvenile work of thirty years ago, 'The Sleeper Awakes,' floating about in it." Which is a fair point. There's no doubt that Lang's masterful film was inspired by much of Wells' work. It's possible that Wells only resented that his own ideas had been, to his eye, bowdlerized for a new medium.

Wells was not above nitpicking, however. He noted that the airplanes of the future looked way too much like modern planes, and that the cars on display were 1926 models. He said that the visuals, often praised by critics for their striking art deco designs and towering expressionistic edifices, are hardly novel, and only represent an amalgam of sci-fi images that he has already been exposed to. Which is a fair point; one can find sci-fi anthologies prior to "Metropolis" that feature similar images on their covers.

Wells had a lot to complain about

More than anything, Wells lambasted "Metropolis" for its dated political attitudes. He felt that Lang's film was at least 30 years beyond anything topical. "Far away in the dear old 1897," he wrote, "it may have been excusable to symbolize social relations in this way, but that was thirty years ago, and a lot of thinking (and some experience) intervene."

More than anything, Wells was perhaps too optimistic to accept the premise of "Metropolis." He writes at length about how an automated future wouldn't require slave-like laborers, and class would, in a high-tech world, vanish. Wells envisioned a semi-communist, almost Gene Roddenberry-like future wherein technology would democratize the world, and there would no longer be a need to differentiate between the rich and the poor. The machines would, he felt, handle all the labor, and the stratification of society would crumble. "What this film anticipates is not unemployment," he wrote, "but drudge employment, which is precisely what is passing away. Its fabricators have not even realized that the machine ousts the drudge."

On this point, in the year 2025, we might be able to accuse Wells of being naive. Here we are in the future, and financial inequality is greater now than it has ever been. He didn't account for the persistent greed and thirst for control wrought by the world's billionaire class. Wells didn't count on capricious wealth-hoarding by immature tech bros. And the drudgery has not passed, and has barely changed form. Technology, I would be saddened to tell him, didn't save us.

Wells hated the end to, describing it thus:

"There is some rather good swishing about in water, after the best film traditions, some violent and unconvincing machine-breaking and rioting and wreckage, and then, rather confusedly, one gathers that [Freder] has learnt a lesson, and that workers and employers are now to be reconciled by 'Love.' Never for a moment does one believe any of this foolish story."

Yowch again.

Wells wasn't the only one

Wells ended his review to observe that "Metropolis" was terrifically popular, and that his screening was full of eager audiences, waiting to be dazzled. Wells had a very cynical view of the audiences, writing:

"I suppose there are multitudes of people to be 'drawn' by promising to show them what the city of a hundred years hence will be like. It was, I thought, an unresponsive audience, and I heard no comments. I could not tell from their bearing whether they believed that 'Metropolis' was really a possible forecast or no. I do not know whether they thought that the film was hopelessly silly or the future of mankind hopelessly silly. But it must have been one thing or the other."

And Wells wasn't the only one who hated "Metropolis" upon its release. The critic for Variety published their review in 1926, and they praised Lang's production design, but were put off by the simplicity of the script. The critic (only credited as "Variety Staff") wrote, "Too bad that so much really artistic work was wasted on this manufactured story."

Of course, in the ensuing century, "Metropolis" has been re-assessed, lost, found, re-cut, re-scored, remastered, and reassembled, and it has now settled into an overwhelmingly lauded realm of cinema. Most of the reviews on Rotten Tomatoes are four-star reviews from expert critics who have had a chance to study Lang's work. It's also important to remember, though, that not every film is going to appeal to every person. Even films you, dear reader, consider to be perfect or unassailable may be deeply hated by critics who, if they're doing their job correctly, will be able to succinctly articulate their viewpoint.

I love "Metropolis," personally, but I can see where Wells is coming from. I am, however, relieved that the remake never came to pass.