Why Logan Director James Mangold Hates Cinematic Universes

It's hard to build a shared cinematic universe, but that hasn't stopped Hollywood from trying, and trying, and trying again. After Marvel proved that interconnected storylines spread across multiple movies was a recipe for box office dominance, everybody started giving it a go. But few have been successful, and none have managed to match the Marvel Cinematic Universe, which remains the biggest box office franchise of all time.

For a while it looked as though the "John Wick" franchise had a thing or two to teach the industry about building a connected universe, but the abysmal "Continental" TV show confirmed what most of us surely knew: that Keanu Reeves was the real draw the whole time. Universal's planned "Dark Universe" also went out with a whimper before it really had a chance to get going, while Warner Bros.' ill-fated DC Extended Universe wrapped up in ignominious fashion in 2023 with a string of box office duds.

But none of this has chastened the industry. James Gunn and his DC Studios are gearing up to try and reintroduce audiences to a new shared DC timeline, with the "Superman" trailer unveiling not just a movie, but a whole new universe. Elsewhere, the guy who turned Winnie the Pooh into a nightmarish perversion of A.A. Milne's original vision has also threatened to make a string of movies in the "Twisted Childhood Universe" that will similarly warp other beloved figures of innocence. There are also several other horror movies quietly building their own shared universes.

But why? Is this all in pursuit of some sort of higher artistic vision that can only be facilitated by stuffing movies with Easter eggs for other movies? Well, according to "Logan" director James Mangold, who also helmed the new Bob Dylan biopic "A Complete Unknown," shared universes are not only far too prevalent, but they also represent the death of storytelling altogether.

James Mangold in the Multiverse of Madness

James Mangold's "Logan" is still heralded as the kind of cerebral superhero movie that Marvel Studios could never hope to recreate. The 2017 film, which belonged to the 20th Century Fox (now 20th Century Studios following Disney's acquisition of Fox in 2019) roster of Marvel movies, depicted Hugh Jackman's hero as a tortured and jaded outcast, with Mangold borrowing from classic films to ensure "Logan" became a true outlier among superhero movies. Adding to its outsider status was the fact that the film had an emphatic ending that wasn't solely designed to set up future outings based in the same universe — which it seems was of the utmost importance to Mangold.

The director spoke about the importance of self-contained stories to Rolling Stone while promoting "A Complete Unknown" — his second music biopic after 2005's "Walk the Line," which featured Joaquin Phoenix as Johnny Cash. Asked whether he ever considered bringing back Phoenix for the Dylan biopic the filmmaker immediately struck down the idea in stark terms.

After being told that "people were somehow hoping ['A Complete Unknown'] would become a cinematic-universe, multiverse return–of-Joaquin Phoenix situation," (who exactly was hoping for this remains unclear), Mangold reacted with a strong condemnation of the concept of a cinematic universe. "I don't like multi-movie universe-building," he said. "I think it's the enemy of storytelling. The death of storytelling. It's more interesting to people the way the Legos connect than the way the story works in front of us."

A Complete Unknown is the anti-multiverse movie

"A Complete Unknown" might be a safe yet enjoyable Bob Dylan biopic, but it's also not entirely typical of the genre. For one thing, the movie is not a retelling of Dylan's life from cradle to the Never Ending Tour, instead focusing on the period between 1961 and 1965. Secondly, the film lives up to its name (itself taken from Dylan's "Like A Rolling Stone") in that it never tries to explain its subject. Dylan ends the film with a past as murky as it was at the start, and that really is the thematic center of James Mangold's feature. At one point, Timothée Chalamet's Dylan even argues with his girlfriend Sylvie Russo (Elle Fanning), who claims not to know anything about her musician partner despite the fact he's been living with her for some time. "People make up their past," Dylan says at the height of their argument. "They remember what they want, they forget the rest."

Whatever you think of "A Complete Unknown," then, it is about something. It's about reinvention, the delicate, nebulous nature of the past, and how we tell ourselves and others stories in an attempt to define our existence. Whether it's successful in interrogating these ideas or not is, of course, up to the viewer. But more importantly, this is what Mangold means when he's talking about the death of storytelling. When a film exists to sell other films in a shared universe, it ceases to become about anything other than that. It isn't a story. As the director went on to tell Rolling Stone:

"For me, the goal becomes, always, 'What is unique about this film, and these characters?' Not making you think about some other movie or some Easter egg or something else, which is all an intellectual act, not an emotional act. You want the movie to work on an emotional level."

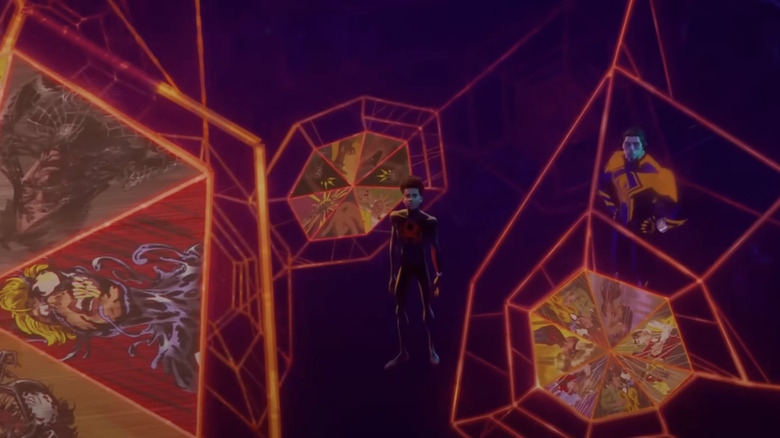

Of course, shared universes don't have to be as devoid of meaning as Mangold makes out. The "Spider-Verse" films are proof that the concept of a multi-verse and shared timelines can directly inform innovative storytelling. With that in mind, it's sort of tragic to think about how the shared universe concept was so quickly subsumed by the Hollywood machine, sapped of its narrative potential and turned into a marketing tool. Let's hope the final "Spider-Verse" movie and its new directors remind us all that shared universes don't have to be such a drag.