Hellboy Creator Mike Mignola's Favorite Monster Movie Is A Universal Horror Classic

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

As the creator of Hellboy and artist of the half-demon hero's many adventures into darkness, Mike Mignola is comics' foremost expert on monsters. Hellboy is an agent of the Bureau of Paranormal Research and Defense (B.P.R.D.) and has vanquished every type of monster under the full moon, from vampires to werewolves to dragons to his demonic kin. "Hellboy" comics range from simple short stories to pulp epics as good as any blockbuster movie; you don't get the modern reinvention of "Creature Commandos" without the B.P.R.D.

But what is Mignola's own favorite monster movie? Despite also being the creator of Hellboy's amphibian sidekick Abe Sapien, it's not "The Creature From The Black Lagoon" and its underwater horror Gill-man.

It's James Whale's "Bride of Frankenstein" and Mignola isn't alone; "Bride" often ranks as the best of the black-and-white Universal monster movies. Whale's movie is so good that Blumhouse has said it's one Universal Horror movie it'll never remake, since it can't beat the classic.

In the foreword of "B.P.R.D. Hell on Earth" Volume 1, Mignola wrote:

"In 'Bride of Frankenstein' (my all-time favorite monster movie), the great Dr. Pretorius raises a glass of gin (his only weakness) and toasts, 'To a new world of gods and monsters.' And in the 'B.P.R.D.'/'Hellboy' world, that's where we are now."

Speaking to Vulture in 2015 about his favorite "Frankenstein" stories, Mignola again listed "Bride" alongside Mary Shelley's original novel, Whale's first 1931 film, "Penny Dreadful," the old Marvel Comics' "Frankenstein," and Bernie Wrightson's beautiful illustrated edition of the book. When recommending "Bride of Frankenstein," Mignola discussed how both Whale's striking images and the melancholy of the Monster spoke to him:

"It's really one of the great movie experiences where you think you know what it's going to be but it's so much weirder, and so much better than anything you could've imagined. It's so full of these striking, powerful images. Frankenstein's monster is essentially crucified on a tree in this wonderful, bizarre-looking forest, or chained into this giant chair. It's just a parade of really great, powerful images. There are scenes in the movie where he's down in this crypt and he says, 'Love dead, hate living.' You know, like, will you make a friend for me?"

Mignola even drew a "Bride of Frankenstein" poster in his own signature style, featuring Hellboy standing alongside Boris Karloff's Creature and Elsa Lanchester's Bride:

You don't have to look too closely to see lots of "Frankenstein" influence throughout the "Hellboy" comics.

Hellboy is a Frankenstein-like superhero

Mike Mignola's influences are vast, from Henry James to Jack Kirby. In the one-shot comic "Hellboy: The Midnight Circus," one of Hellboy's guardians takes the young demon to a library so he can learn to read something besides comic books; this feels inspired by Mignola's own love of reading.

"Dracula" is the horror novel that most inspired Mignola, and in "Hellboy: Wake The Devil," he gives thanks to "Dracula and all those other vampires I've loved." "Hellboy: Conqueror Worm" is titled after an Edgar Allan Poe poem (with lines from that poem included), and features a similar thank you to old pulp heroes like Doc Savage and the Shadow.

"Bride of Frankenstein" is Mignola's favorite monster movie, but there's another Boris Karloff horror picture he likes even more: 1945's "The Body Snatcher," where Karloff plays an articulate and sinister grave robber instead of the lumbering Creature.

Hellboy, as a character and comic, is the ultimate synthesis of everything Mignola loves. Sometimes described as a "paranormal investigator," he's got the attitude of Philip Marlowe but handles cases out of the occult. He's also (in a solely literal sense) a monster himself. Though mostly accepted by humans, Hellboy can never totally cross the bridge to become one of them — he's a lot like Frankenstein's Monster and his quest for companionship.

"Bride of Frankenstein" diverges from Shelley's book but it better adapts the Monster's tragic side. For one, it includes the sections of the book where the Monster tries to befriend a blind man only to be chased away again by people who can see his appearance. The Creature desires a Bride because of his loneliness, of course, and when she too recoils at the sight of him, his despair is complete.

Guillermo del Toro's "Hellboy" movies especially play up Hellboy's outsider-ness. The filmmaker, a huge "Frankenstein" fan who is making his own adaptation of Shelley's book, clearly responded to the glimmers of isolation in Mignola's Hellboy and amplified them.

As played by Ron Perlman and drawn by Mignola, Hellboy has a thick jawline that rivals Karloff's square-headed Creature. The difference is that Hellboy is articulate and not a murderer; he gives kids smiles and lollipops instead of drowning them. The Creature decided to lash out at a world that rejected him. In numerous "Hellboy" stories, monsters tell Hellboy to start the apocalypse already, and he always tells them to go screw themselves, twice ripping off his own horns to show him refuting his destiny. (Hellboy never wears his horns fully grown to make himself look more human.)

It helps that, unlike the Creature, Hellboy had a father who loved him: Professor Trevor "Broom" Bruttenholm. In the climactic mini-series, "Hellboy: The Storm and the Fury," Hellboy glimpses a sign reading "the end is nigh," and feels solemn, knowing he was brought to Earth to cause that end. So, Hellboy remembers a moment from his childhood when Broom reassured him he's no Frankenstein's Monster:

Bride of Frankenstein opened Hellboy's world of gods and monsters

The Universal "Frankenstein" films are set in gothic castles surrounded by rustic, cobble-stoned villages; the films take place in the 19th century, but the settings could pass as taking place in the 16th. Many "Hellboy" stories have similar settings, especially the early ones; European cities filled with older architectural styles are just spookier than urban America.

"The Corpse" features Hellboy carrying a talking corpse through the English countryside at night, trying to find him a proper resting place before dawn. "The Wolves of Saint August" sees Hellboy investigating a forgotten village called Griart, cursed by werewolves and the undead. (Did anyone call Larry Talbot, the Wolfman?) In "The Chained Coffin," Hellboy returns to the Scottish castle where he first arrived on Earth; he witnesses the demon Azzael, his very own father, ripping open a coffin to get at the soul of a repentant Devil-worshipper.

Mignola excels at drawing dark castles. (Hellboy's red skin, supplied by colorist Dave Stewart in most comics, always brings eye-catching contrast when he's surrounded by black.) But he doesn't only use the settings for horror; in "The Vampire of Prague" (drawn by P. Craig Russell) Hellboy chases a vampire through the foggy city with some "Looney Tunes" style comedy.

Of course, castles are much scarier with twisted scientists and sinister laboratories inside them. One of the most recurring Hellboy villains is Herman Von Klempt, a Nazi-scientist with his preserved head in the jar; Von Klempt is served by cyborg gorillas of his own making, and unafraid to cross the field between life and death, whether to create an army of vampire clones ("B.P.RD. 1946") or summoning a serpent to turn the world into a ruined cinder ("Conqueror Worm").

Disturbing Nazi scientists are right out of WWII American pulps (see also: Captain America's archenemies Red Skull and Baron Zemo), but their outlandish schemes to control or mutate life inevitably invoke "Frankenstein." They do the same thing in "Hellboy." Von Klempt is the Dr. Pretorius of Hellboy in his life-perverting ambitions, but all of Hellboy's major enemies seek a "new world of God and Monsters," from the Mad Monk himself Rasputin to the serpentine goddess Hecate to Nimue the Witch and her challenging-to-draw raven helmet.

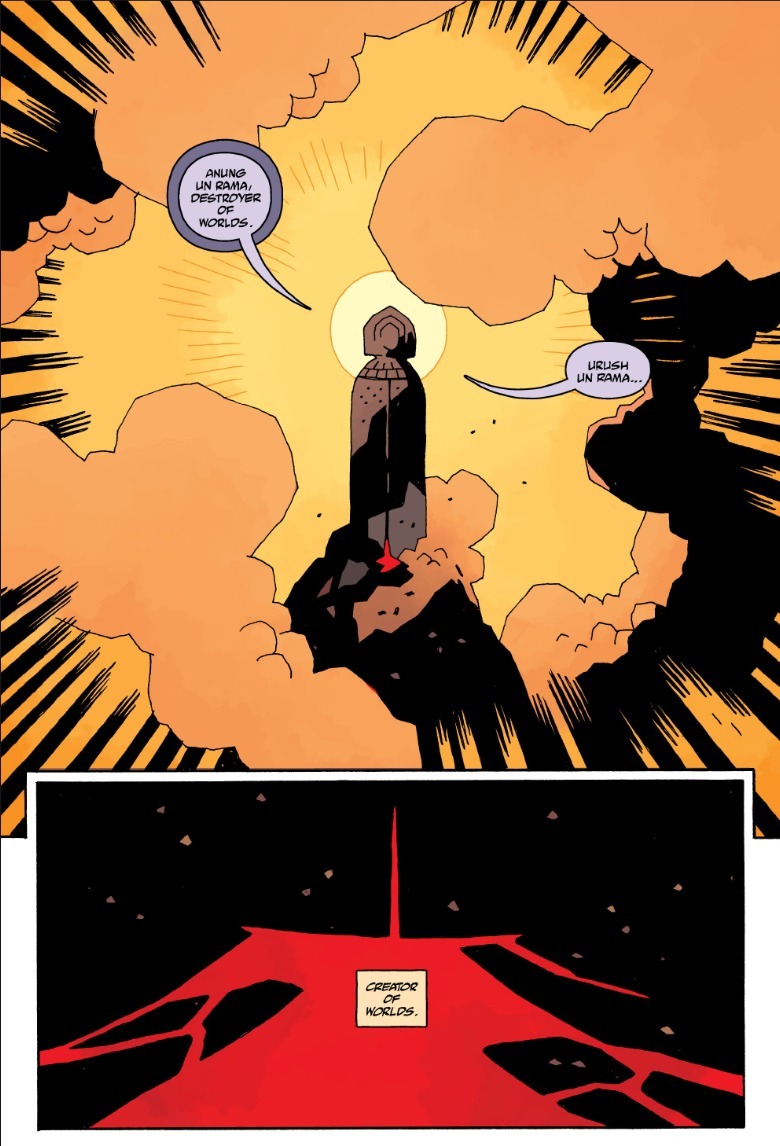

In a 2012 conversation with "B.P.R.D." writer John Arcudi, Mignola noted how his bad guys have a Frankenstein-like impulse to change the world: "All my major 'villains,' starting with Rasputin, have sort of been on the side of evolution — moving the world forward towards its destruction, making a rebirth possible. The whole destruction of this world to make way for the next is lifted right out of Norse mythology — Ragna Rok."

Mignola's ability to draw creatures, giving birth to terrors from his own imagination, makes him something of a Dr. Frankenstein himself (even if limits his experiments to ones with pen and paper). Guillermo del Toro's "Hellboy" films make some changes to the comics, but his skill at building monsters rivals Mignola's. The filmmaker reimagining gas-masked Nazi scientist Kroenen as a clockwork assassin with retractable swords mounted to his arms? That rules.

Roger the Homunculus is Hellboy's Frankenstein

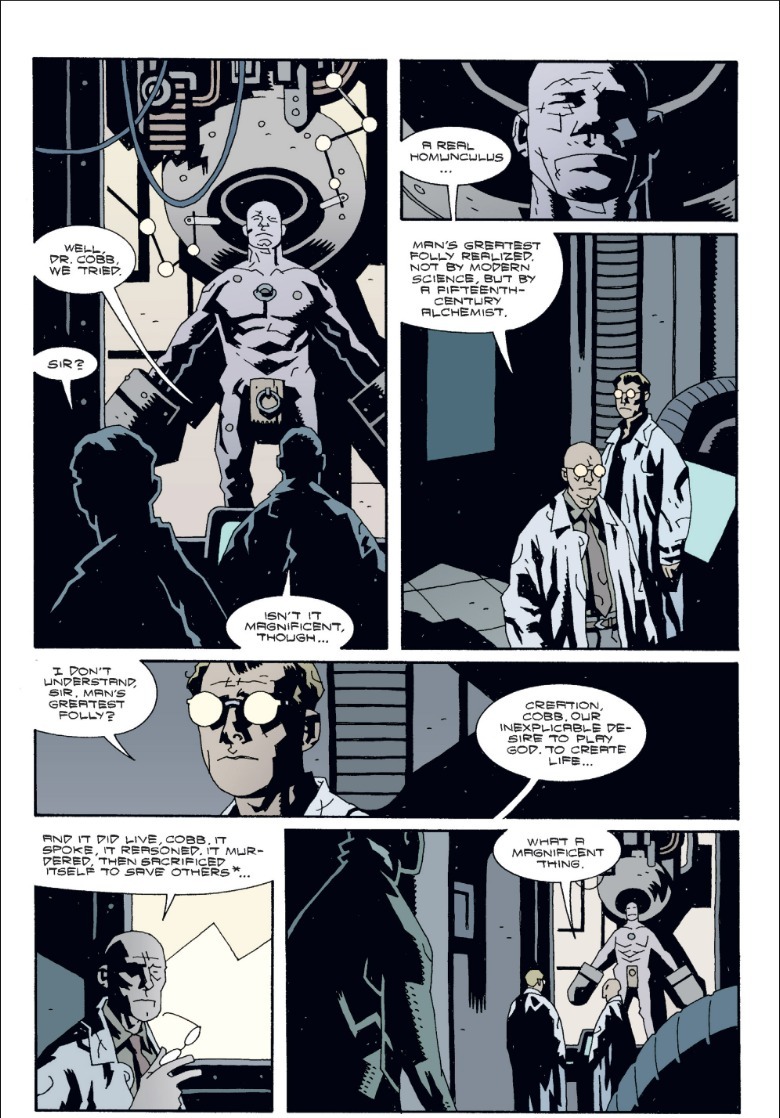

Mignola eventually brought Frankenstein's Monster himself into the "Hellboy" universe (or "Mignolaverse"). He debuted in "Hellboy: House of the Living Dead," and then got his own spin-off comics "Frankenstein Underground" and "Frankenstein: New World." But "Hellboy" had a Frankenstein analogue long before that, as part of the B.P.R.D. even.

"Wake The Devil" (another "Hellboy" comic set in castles and crypts) is mostly a "Dracula" homage. One of the story's villains is an ancient vampire, Vladimir Giurescu. But there's also a "Frankenstein" send-up buried in the story. In one of the castles that the B.P.R.D. is investigating, Liz Sherman finds an ancient alchemist's laboratory and, inside, an inert homunculus, which she brings to life with her fire-starting powers.

In Shelley's "Frankenstein," Victor is inspired by ancient alchemists, such as Paracelsus and Albertus Magnus. Compared to the limits of modern medicine, Victor finds the wonder of alchemy is not fantasy, but an ambition to reach for. Him creating the Creature (through more nebulous means than later adaptations) feels derived from the myths of alchemists creating homunculi or artificial humans.

James Whale's "Frankenstein" doesn't have the same alchemy references and invented the new origin for the Creature: stitched together body parts reanimated by lightning. "Bride of Frankenstein," though, calls back to alchemy when Dr. Pretorius reveals he has created several little people in jars. "Miniature human" is the classical meaning of homunculi (see also: "Fullmetal Alchemist"). In "Hellboy," a homunculus can be brought to life with lightning, melding Whale's interpretation of "Frankenstein" with the myths Shelley pulled from.

This homunculus, eventually named Roger, goes on the run and the chase for him takes up the sequel, "Almost Colossus." Roger prays for a place in the world, only to receive an unexpected answer: a "brother" in the form of another homunculus who killed their creator and wants to ravage the world of humans. Roger and his brother embody the two halves of "Adam" Frankenstein; one vengeful at the world and his creator, the other one longing to be accepted by them.

The ending of Hellboy sees the creation of a new world

"Bride of Frankenstein" has a bleak ending, with the Creature blowing up Dr. Pretorius' lab to kill the doctor, the Bride, and himself, saying "We belong dead." Far from ushering in a new world, these weirdos just couldn't fit into the existing one.

While the B.P.R.D. crew are mostly working Joes who accept the human world, many other "Hellboy" monsters are outsiders. The Fae are disappearing from the world, while the witch Baba Yaga makes her own pocket dimension for an imaginary Russia that never existed.

The 10-issue "Hellboy In Hell," following Hellboy's afterlife after his death in "The Storm and the Fury," is a very lonely comic. Cut off from the world he knew and everyone he loved, Hellboy spends the comic drifting like Karloff's Frankenstein. He spent so long trying to fit in on Earth, but he was always bound for Hell. In the end, he lived a good life — the last panels of "Hellboy in Hell" show Hellboy arriving on Earth in 1944 as a child, encouraging you to read his life story in a loop.

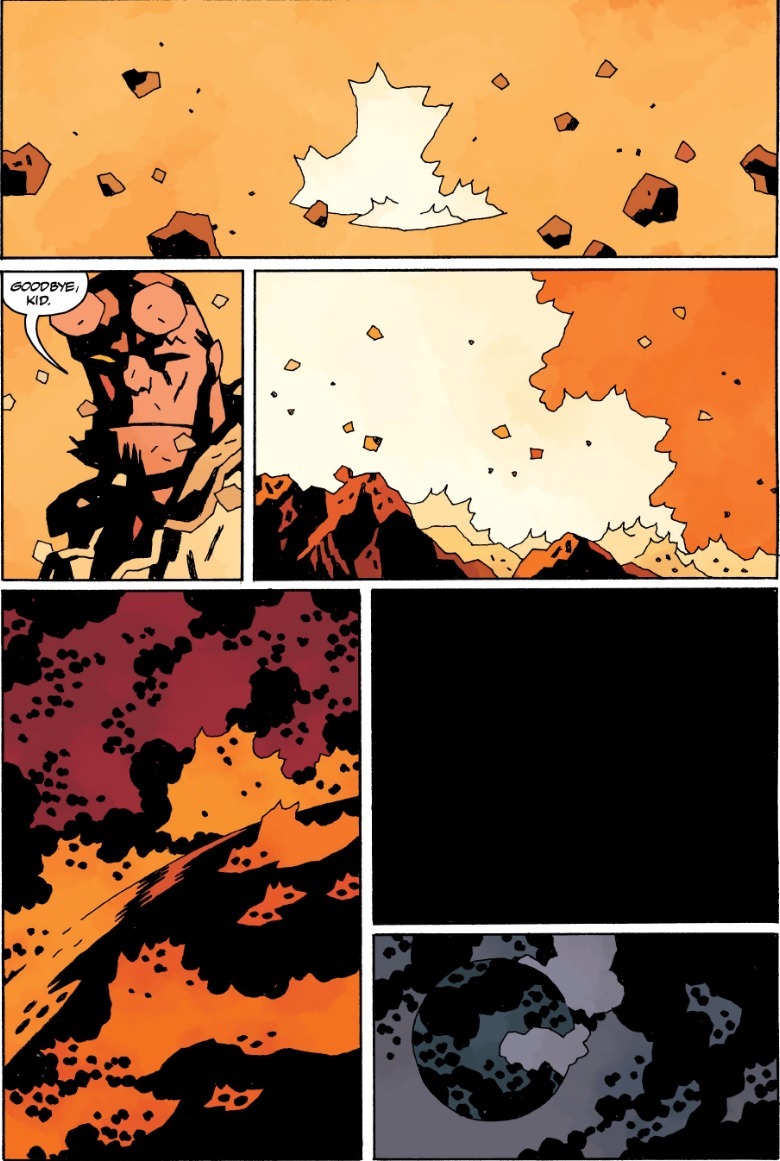

"Hellboy In Hell" works as an ending, but Mignola ultimately brought his hero back for one last hurrah in "B.P.R.D. The Devil You Know." It's a more conventional full-circle ending where our original trio of Hellboy, Abe, and Liz face their first foe Rasputin at the end of the world. But it's just as fatalistic, as events foretold long ago in "Conqueror Worm" finally play out. Abe dies and Liz burns the monster-infested Earth all down; like "Bride of Frankenstein," this story ends in a fiery explosion, one that destroys not only a castle but also cleanses the whole world.

Hellboy, in a final act of selflessness, gives his life over to Hecate. You see, Hellboy's spilled blood creates white lily flowers — the final panel of "The Storm and the Fury" featured such flowers blooming in the rubble, showing how Hellboy's first death saved England and created a kernel of hope. His final death does the same for the whole world, rejuvenating it as his blood flows across it. Humans find a new home underground in the hollow Earth, while a race of frog-men spawn from Abe's corpse to inhabit the surface.

Few superhero comics end as definitively as "Hellboy" and "B.P.R.D." did, and in that conclusion, Mike Mignola's hero became the creator god of a new world of monsters.