The Forgotten Horror Novella That Kicked Off The Vampire Craze Years Before Dracula

Vampyr. Upir. Dracula. Nosferatu. The ever-evolving vampire myth, which can be traced all the way back to A.D. 1047, has given many names to the dangerous, alluring entity at the center of these frightening folkloric tales. In every iteration, the vampire's natural state of existence was considered parasitic, which quickly became synonymous with the rise of untreated diseases that plagued the world at the time. The act of feasting on another, fangs bared, also had a sacrilegious overtone, wherein the sullying of the soul weighed heavier than the physical implications of being attacked. After Bram Stoker incorporated these myths about the undead into his 1897 gothic horror novel "Dracula," an enduring shift took place in the public consciousness, its relationship with vampire myths, and how they would be reinvented for years to come.

Robert Eggers' "Nosferatu" (read /Film's review), which is an astounding, boundary-pushing culmination of more than 100 years of vampiric history, reworks Stoker's tale on a visceral level. Sure, the core framework for Eggers' latest work is F. W. Murnau's "Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror" — an unofficial, unauthorized adaptation of Stoker's novel released in 1922 — but the film draws upon tenets of the vampire myth that both precede and eclipse "Dracula." However, no matter how a vampire tale is reimagined, literary imagery/themes from "Dracula" seem subconsciously branded into our very understanding of how these supernatural creatures skirt around the sacred and the profane (to mention nothing of their influence on other movie monsters).

A lone count living in a ruined castle migrating to infect an oblivious populace, innocence being lost once the undead feeds upon the living, or the sensual, forbidden nature of being enamored by the "other." These are just a few "Dracula"-coded themes and motifs that have shaped our perception and consumption of vampire myths, from the "Twilight" saga to "The Lost Boys."

Having said that, our obsession with vampires owes a great debt to a criminally overlooked gothic horror novella that predates Stoker's "Dracula" by over a quarter century. Let's (finally) talk about Sheridan Le Fanu's "Carmilla."

Carmilla is one of the first literary vampires to come before Dracula

Spoilers for Le Fanu's "Carmilla" to follow.

Le Fanu's 1872 "Carmilla" is a genre prototype on many fronts. It is one of the earliest works of vampire fiction and features the first lesbian vampire to ever exist. The novella's protagonist, Laura, is a young woman residing in a castle in Styria (present-day Austria), and her complex, escalating relationship with Carmilla, who appears all-too-sweet and human, forms the crux of the allure and horror of Le Fanu's defining work.

The seeds of terror are planted years before the story's core events occur. Laura describes being visited by a beautiful woman who punctured her chest when she was only six but had left no wounds behind. The way Le Fanu frames this unsettling childhood memory is especially chilling, with Laura witnessing the woman twist and hide under the bed once she cries out for her nurses in fear. Although the nurses do not find anyone in that cramped space, the floor feels warm to the touch, as if someone had, indeed, laid there seconds earlier.

How does Le Fanu depict Carmilla, the vampiric seductress who wants to claim Laura's body and soul? At first, Laura views Carmilla as one would a like-minded young lady of high standing, but admits that she is more beautiful, mysterious, and unpredictable than anyone she has known. At times, Carmilla is earnest, soothing Laura's loneliness by emerging as a steady companion who can be confided in. However, these mellow periods are often punctuated with bouts of obsession, with Carmilla overtly confessing her attraction and need to consume Laura. "Darling, darling, I live in you; and you would die for me, I love you so," Carmilla states in a trance, the implications being explicit and overtly queer. Although Laura uses terms like "disgust" and "revulsion" when met with these advances, her relationship with Carmilla is undoubtedly tinted with unstated temptation, which she continuously rejects lest she "transgresses."

These sapphic overtones mingle with the horror of being possessed or defiled, as Carmilla continuously feeds on an oblivious Laura every night. Moreover, her customs are perceived as "strange." She never rouses before noon, does not partake in the household prayers, and her moods swing to inexplicable extremes. So, what is Carmilla and what does she want?

Carmilla's legacy looms larger than you think

Let's talk about the vampiric tropes in "Carmilla" that inevitably trickled down to Stoker's novel and everything that came after. Although sunlight does not burn Carmilla (or make her sparkle), she avoids direct exposure, which could mean it weakens her kind (this also explains her daytime sluggishness). Moreover, Laura's household notices that Carmilla sleepwalks, but this is just her on her nightly prowls, attacking and killing young women in the area, who seem to have died from a mysterious malady. On some nights, Laura witnesses a black beast looming over her bed, which later transforms into Carmilla, whose white nightgown is drenched in blood. This seems to be a precursor to Dracula's ability to transform into various beasts in Stoker's work, wherein the vampire-bat connection stood the test of time and is still being used today.

While Dracula's victims are arbitrary, and his targeting of Lucy Westenra and Mina Harker was part of an elaborate plan of operatic proportions, Carmilla's victims are all women. Although unclear, it is likely that she "marks" some of them as children (which ties back to Laura's horrifying childhood memory), and returns years later to pose as a guileless, friendly companion. Laura is not the only woman Carmilla has seduced in the novella, and it seems that her sexuality (considered transgressive for the times) is an integral aspect of her process of claiming, consuming, and killing her targets. Although Carmilla's morality (or absence of it) is framed as unnatural and sinful, she appears authentic in her avowals of love, as if every conquest is a justified, impassioned step towards preserving her undead, otherworldly existence.

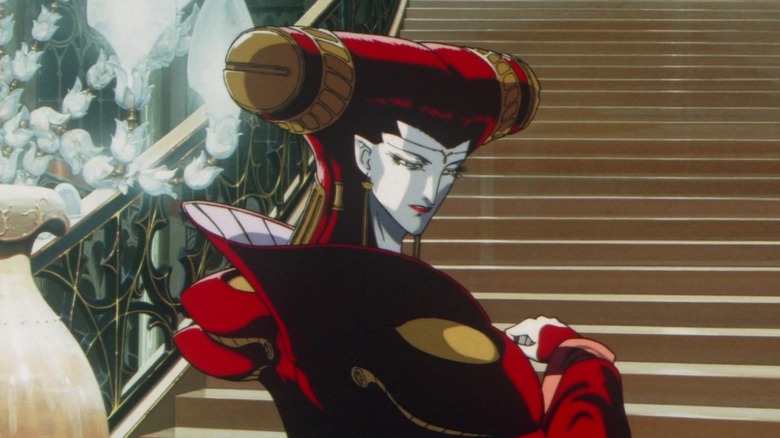

Without "Carmilla," it is hard to imagine the formation of literary traditions that are considered foundational to the vampire myth, and how it has been constantly restructured since then. Her more recent namesake, the vampire Carmilla from the "Castlevania" and "Vampire Hunter D" franchises, is a reminder that the ruthless female vampire exists, rife with complexity, uncompromising ambition, and the freedom to explore the desire/death dichotomy. I can only hope that Carmilla's undeniable pull will be acknowledged in due time, the effect haunting and immediate like the final image of her submerged in a coffin filled with blood.

"Nosferatu" opens in theaters on December 25, 2024.