Heretic Directors Reveal The Real-Life Cult Leader Who Inspired Hugh Grant's Villain [Exclusive Interview]

In a year full of terrific (and terrifying) horror movies, "Heretic" stands out from the crowd. Driven by captivating dialogue and a simmering sense of dread that eventually boils over into outright terror, the writing and directing duo of Scott Beck and Bryan Woods have done the impossible: They've made an A24 horror movie that captures the studio's trademark sense of unease while also delivering a proper crowdpleaser. It's the kind of movie that feels carefully built to appeal to horror fans ranging from arthouse to casual, all without sacrificing character, atmosphere, and yes, scares. As I wrote in my review from Fantastic Fest, this is simply an extremely good time at the movies.

And delivering extremely good times at the movies is what Beck and Woods do best. After writing "A Quiet Place," they directed two of the most underrated genre films of the past few years with "Haunt" and "65." "Heretic" is their best movie yet, and evidence that these two are among the most exciting folks making horror and science fiction movies at the moment.

I sat down with Beck and Woods over Zoom ahead of the November 8, 2024 opening of "Heretic" to talk about the movie, including what it's like to direct Hugh Grant (in his first horror movie, no less), the real-life inspiration for the film's chilling and charismatic villain, and the tricky nature of writing horror movie protagonists who are smart enough to escape most other scary movies (but not necessarily this one).

Note: This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

In some ways, Heretic was meant to be the opposite of A Quiet Place

I want to talk about the literal technical aspects of filming dialogue scenes, because so much of this film is talking. As filmmakers, how do you look at a scene with dialogue that lasts for five, ten, fifteen minutes and keep it interesting? How do you approach it visually?

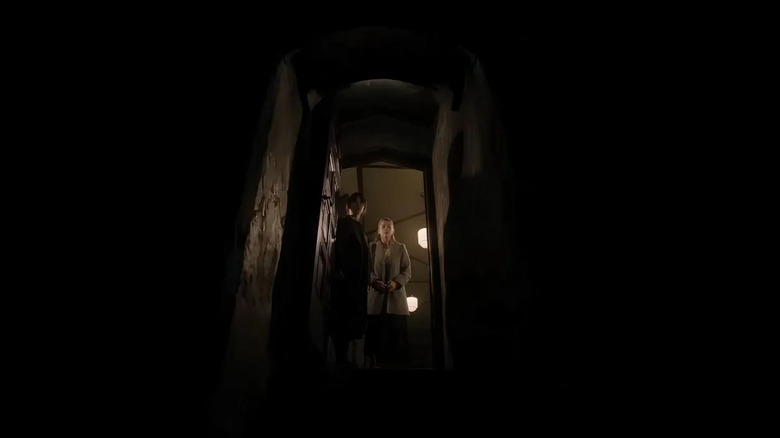

Scott Beck: Yeah, I mean, I think the first and foremost approach is character-centric, like understanding who are the characters that we're focusing on from their perspective and how are we feeling emotional with them? So a scene in "Heretic," for instance, like the initial living room scene where Sister Pax and Sister Barnes first meet Mr. Reed, Hugh's character, we want to make it feel very open. This is a very open space. It's not claustrophobic. Everybody feels welcome here. So you're shooting it more from wides, but slowly the camera starts creeping in, for instance, as Reed starts singling out each of the sisters. He's trying to hone in on them psychologically, so we're creeping closer and closer. And in doing that, especially over the course of the film, allowing the camera to have a little more motion. So at first in this film, it starts off a little dull, the camera's in stasis, but as we go deeper into the house, as we go deeper into the danger, the camera starts to move.

Bryan Woods: It was one of our biggest fears because it's such a chamber piece, it's so dialogue-heavy. The experiment with this film, it was almost the opposite of what we were attempting to do with "A Quiet Place." "A Quiet Place" was like a modern day silent film, so it was all about pure cinema. This was, can we replace jump scares and monsters hiding in shadows with dialogue and philosophical ideas? Can we actually take a conversation about religion and those are the scares? Like the dialogue, the lines themselves are the scares in the movie? And so that's when you hire Chung-hoon Chung who shot "Oldboy" and "It" and "Last Night in Soho," one of the great cinematographers in cinema history, to help us drag the dread out of every single frame of the movie while our characters are debating theology.

One of the most interesting and frightening things about Mr. Reed is that I find myself, especially in the first half of the movie, kind of nodding along with what he's saying. What's the trick to writing a villain who is definitely the villain, but you kind of find yourself going, "Maybe this guy has a point"?

Scott Beck: I think the trick is he's saying the quiet parts out loud. The things that we've all felt in our bones or the things that we've had conversations with friends behind closed doors, about true beliefs or true questions about things that otherwise outwardly maybe we put ourselves in uncertainty when we otherwise discuss them. And I think trying to be as personal as possible. The ideas that this movie starts to grapple with [are], what happens when you die? Is there an afterlife? Is there nothing? Those are very real fears that Bryan and I have had and have had many conversations about. And it's a very human tendency to want comfort in the anticipation of what happens when you die, whether you find that comfort in following a religion or some other output. These are all things that we felt like Reed could be speaking a degree of truth in terms of what we've all thought about from an existential standpoint.

The directors of Heretic were always thinking about the audience

Was there ever a version of this movie that was entirely dialogue-driven? You do get to the fireworks factory eventually, to use a reference. But was there ever a version where you wanted to push the dialogue even further?

Bryan Woods: Well, I mean, listen, I both appreciate that you feel the fireworks factory gets ignited at a certain point, because we do want to deliver cinema and this was never a stage play to us. We are movie lovers and we wanted a movie to play in a theater and take the audience on a ride. But I'll also say, to us, the movie really is dialogue from beginning to end, even though the fireworks start to go off at a certain point. We are constantly keeping our characters in dialogue with each other, all the way up until the final moments, because there were different — I guess what I'm saying is there were different versions of this ending and movie and third act that were exclusively the kind of visceral visual thrills that you would maybe expect out of a horror film. And we felt, at least our ambition was, we always wanted to bring it back to the conversation, even in the third act. So that's what we're attempting to do.

I revisited "Haunt" and "65" recently. One thing, maybe a surface level, that your movies have in common is that they remind me of a Christopher McQuarrie quote I'm going to paraphrase about how the audience is king. You make movies for the audience, not for yourself. I'm wondering if that's true with you, because I feel like your movies are designed to send the audience out buzzing.

Scott Beck: We take it very seriously. I mean, I think we are in the entertainment business, and so first and foremost, we want something that feels like a theatrical experience, that you want to go to a movie theater and sit there with hundreds of strangers and experience this thing and also feel it percolate around the audience. And I think there's also a degree at which Bryan and I, there's two of us, and so even in the writing phase, we're not writing in the same room, so we're usually trading off scenes or sections of the script and the other becomes the first audience for that movie, even in script stage. So we want to constantly surprise each other. We want to subvert expectations. So we're automatically thinking from an audience-forward perspective that early in the process.

Bryan Woods: And it's funny because it's not something we've ever intellectualized or talked about because we write for ourselves, too. There's a personal relationship we have with the material that we're trying to thrill ourselves. But our production designer on "Heretic," Phil Messina, who's one of our heroes — I mean, he has production designed anything from Aronofsky's "Mother!" to the "Hunger Games" movies to like 12 Stephen Soderbergh movies — it was an observation he made working with us that he had told one of our producers that he's never heard directors talk about the audience so much while directing. So it was subconscious that I guess we do love to serve an audience, and I guess it's just our deep love of going to the movies on a Friday night with a packed house.

Keith Raniere of the NXIVM cult inspired Hugh Grant's Mr. Reed

I'm glad you brought up the production design, because the house in "Heretic" is fabulously designed. What was the process of determining the look and feeling of each room? You can kind of break down the movie into act one, act two, act three based on rooms. What was the journey there?

Scott Beck: Yeah, I mean, the initial journey, it mimicked the character of Mr. Reed as well. Meaning, you get into the first room and you see something that feels fairly inviting, fairly warm with the colors and the tones and the lighting. And then as you progress throughout the movie, it starts getting a little stranger by increments. You start picking up on small details, strange things like the doors once you get into the library sequence. And then it starts getting a little more raw and a little more dangerous and scary in the same way that Mr. Reed becomes that. And one thing that Phil Messina, our production designer, is so genius about is being character-forward and really enveloping every single decision that he makes into the larger scope of the character, into the sound design, from the ticking of the clocks to the ticking of the water and these devices like the shishi-odoshi inside the library that drips the water, and finding ways to accentuate the suspense and make sure there was an evolution over the course of the movie that feels organic and genuine, but also more and more suspenseful and off-putting.

You called the movie a chamber piece. And it did remind me a lot of the '50s and '60s horror films that you would've seen like Vincent Price star in. It kind of clicked in my head that, oh man, if this was made in 1962, then Price would've played the Hugh Grant character.

Scott Beck: Yeah.

So I'm wondering, how much Vincent Price is in Mr. Reed?

Scott Beck: I mean, there is a degree that you are right on the money. I think about the way that Hugh wanted to be fun with the role, highly intellectual but very charming as well. And I feel like you can look at Vincent Price and you can trace all those attributes. Even the sweater that our costume designer Betsy Heimann picked out, I feel like you could envision that in black and white on Vincent Price. So I mean, as students of horror since the beginning of the genre in the 1920s, I think latently that feeds into everything that our fingerprints start putting itself on.

Bryan Woods: And I do think mostly when we were talking about Reed, in particular with Hugh, there's just a lot of real-life inspirations, oddly enough. You can look at the kind of atheist thinkers out of the UK like Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens. There's American kind of cult leaders like Keith Raniere, we talked a lot about Keith Raniere of the NXIVM cult, and how he was able to use this almost odd charm [and] this ability to listen, to get people to do what he wants and to control them. So there's a lot of real-life influences intersecting with the kind of more showmanship of a figure like Vincent Price.

Hugh Grant crushed 'take after take' while making Heretic

In a recent interview, Hugh Grant described his current phase of his career as his "freak show" phase, which I thought was funny, but also undersells how good he's been over the past decade and how interesting he's been. As an actor on that set, what is he like to direct during his freak show phase?

Bryan Woods: He's great at underselling himself, to your point, he's a great under-seller. Working with Hugh is like, he'll show up on set and he'll go, "All right, well, you know, let's just do a really bad, just a bad version. No acting. We don't need to act. We'll just read. We'll just say the lines. Just say the lines. It's not a big deal. Let's just say the lines. It'll be fine." And then he'll just show you the most amazing performance you've ever seen and just crush take after take.

There were scenes where there'd be 10 pages of dialogue and we would kind of all amongst ourselves agree, "All right, let's just do five pages." And five pages is like climbing Mount Everest. "Let's just do five pages, let's do half of it, it'll be fine. No pressure, no pressure." And then he would crush it. He would go all the way through 10 pages, put a cherry on top, we'd call cut, the crew would burst out into applause. It felt like watching live theater, it felt like watching, I don't know, Daniel Day-Lewis at the top of his game. It was really something special to see, and we can't be more grateful for what he gave to this film.

Sister Barnes and Sister Paxton are depicted as being really smart, canny characters. How would you escape the pitfalls of writing characters who are smart enough to escape the average horror movie but not smart enough to escape your horror movie?

Scott Beck: Yeah. I think the balance and the gut check that we have early on is being allergic to convention or being allergic to the obvious answer of how you get yourself out. So if you put your characters — I mean, I think we first encountered this when writing both "Haunt" and "A Quiet Place," seven, eight, nine years ago, where it's like, you get your characters into situations and we as the writers or directors may know where we want to go next with them, but if the characters start pushing up against that and being like, "No, I'm smarter than the next scene that you want to write," we try to follow that instinct. We try to make sure that we are being as genuine and surprising to ourselves during that early process as possible so that we don't just, we're like, "Ah, but this character has to go into the next room," and so we're just going to write them going into the next room.

It's like, no, if they need to go through the exercise of, "This is dangerous. I need to try the door, I need to try the window first," they're going to do that and we're going to have to engineer and try to think on our feet and push ourselves to be a little more ahead of these characters and the audience as possible. What that usually brings up is we find ourselves in more unpredictable situations, and that's really where the exciting place is to start creating the scene and creating the movie, to surprise ourselves and go to the unexpected.

A24 is not interested in pandering to audiences

The "A24 horror movie" has become its own sub-genre. Somebody asked me a little while back, what's "Longlegs" like? I said, "Oh, it's like an A24 horror movie, even though it's a Neon release." What is the inside process of making an A24 horror movie?

Bryan Woods: I mean, if I ... having worked with them, our feeling, they were one of our favorite studios just as film lovers. And now being the behind the curtain, you can see why, which is basically: They love movies, they support their filmmakers, and they're ambitious. They want to do hard, challenging work, and that does kind of personify the brand of A24 when you see their movies. But there's no self-awareness of "This is what we're really doing." I actually felt like it was mostly, it was the bravery.

There's a moment — every movie you make, especially when you're making studio films, but we've seen this even with independent financiers, there's this kind of instinct to satisfy the audience to the detriment of the movie that you're making or the story that you're telling or the point that you're trying to make. There's this kind of like, "We have to satisfy the audience," and A24's not interested in that, in a really powerful way. They want to tell the story and they want the best story. And I just think, honestly, I think they have a little bit more courage than a lot of other places. But yeah, there's no question that Neon's doing exciting work, and there's no question that A24 probably gets credit for movies that maybe they didn't necessarily produce at this point.