Clint Eastwood's Best Film Of The '80s Was Dirtier Than Dirty Harry

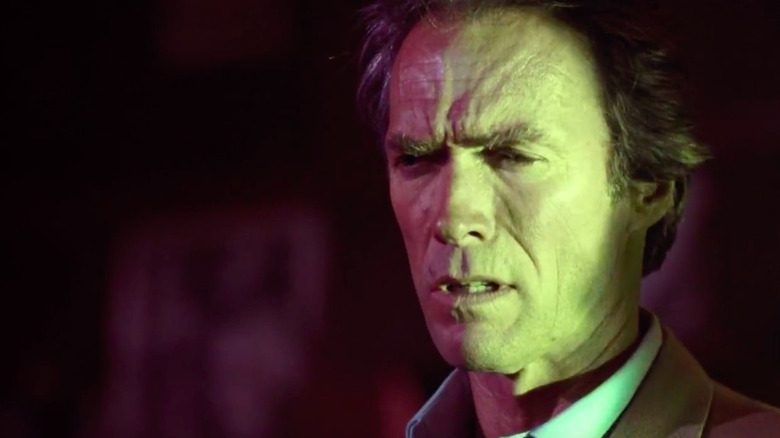

The term "icon" is grossly overused when discussing artists and celebrities, but it applies to Clint Eastwood. Between his pivotal role in the popularization of the Spaghetti Western and his revolutionizing of the crime film with his five-film portrayal of "Dirty" Harry Callahan, you could say there wasn't a more important actor throughout the second half of the 20th century and no one who knows the terrain would take issue with your assessment. Eastwood wasn't just an international movie star, he was, for good and ill, an avatar for law and order in America. He played violent men who uncomfortably lived by simple codes. His characters typically "won," but they paid a sometimes terrible price for triumphing. They compromised their values. They placed loved ones in harm's way. They punished themselves for punishing others (or just behaving like a lout). And once upon a time, audiences were in the market for Eastwood's brand of ambiguous heroism.

There arrived, however, a moment in the early 1980s when that ambiguity seemed in danger of being replaced by the kind of fist-pumping vigilantism Eastwood had resisted since he pulled a .44 Magnum on a wounded perp and asked after his sense of good fortune in Don Siegel's prickly 1971 classic "Dirty Harry." The star was still exploring the fragility of male identity in very good movies like "Bronco Billy" and "Honkytonk Man," but he'd begun to pander to meatheads with dross like "The Gauntlet," "Every Which Way But Loose," and "Any Which Way You Can." I'll admit the orangutan duology has its dips*** charms (Clyde taking a crap in a squad car may be the most anti-cop moment in Eastwood's oeuvre), but a cruel streak was creeping into his work.

This ugliness exploded off the screen in 1983's "Sudden Impact," the fourth Dirty Harry movie and a film so silly and rancid that it almost plays like "The Naked Gun: From the Files of Inspector Callahan." Eastwood's high-caliber cop is shockingly inept in this nasty yarn about a rape victim killing off her assailants one-by-one, her calling card being that she shoots them all in the crotch. Sounds amazing, right? Had Eastwood given us the Callahan of the first film instead of the inept clown who bumbles his way through the investigation in this movie, it just might've been. Instead, it's a clumsily directed action movie pervaded by misogyny, homophobia (the most hissable character is a sadistic lesbian) and all-around misanthropy. Everyone's cruddy in this film.

"Sudden Impact" got savaged by most prominent critics, who expressed disappointment that this smart, accomplished filmmaker-star was willfully becoming the red-meat, Reagan-era conservative onscreen that may assumed he was off of it. The United States' actor-turned-president appropriating Dirty Harry's withering "Go ahead, make my day" utterance felt definitive. Eastwood had given up on nuance and succumbed to the bloodthirstiness of Charles Bronson's extrajudicial fantasies.

What the heck was wrong with Eastwood? Nothing the sleaziest movie of his career, and his best of the 1980s, couldn't fix.

Introducing Kinky Harry

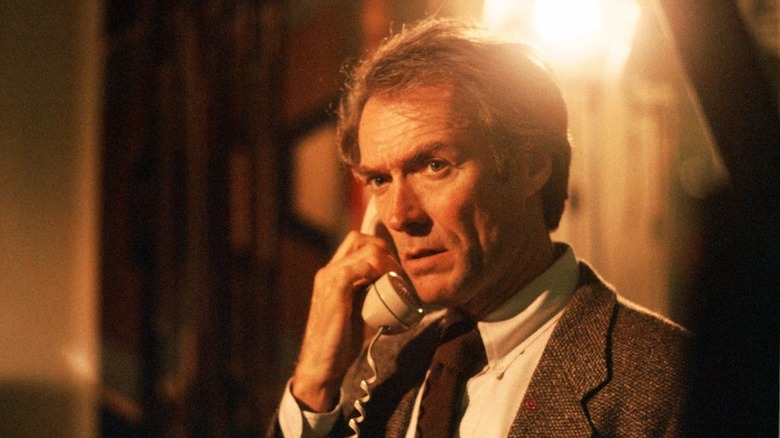

"Tightrope" was slickly positioned as more of the same from Eastwood. Warner Bros. cut a trailer that led with the misleading implication that it was a serial killer thriller wherein everyone from Eastwood's character to the mayor are under suspicion. They're not (the film makes this very plain by showing the perpetrator's face, thinly masked in shadow, in its opening scene), but this bait-and-switch didn't bother moviegoers. "Tightrope" was a critical and commercial success. It topped the box office on August 17, 1984, and remained at number one for the next three weeks (fending off challenges from "Red Dawn," "Ghostbusters" and "The Karate Kid"). It was Clint as a cop, and audiences seemed generally unfazed by the film's highly provocative content because, if nothing else, it was properly rated R (unlike "Red Dawn," which some media watchdogs felt exploited the laxness of the then new PG-13 rating).

40 years later, the film's screenwriter Richard Tuggle thinks its treatment of forensics as a novel investigative tool might seem dated, but its depiction of a cop whose personal kinks intersect with the m.o. of the murderer still resonates. As he told me in an interview, he was inspired to write the script after reading about a string of rape-murders in the Bay Area. Given that he'd worked with Eastwood, he initially saw it as a standard cop thriller. "I'll have some cop, some Dirty Harry guy chasing a rapist," said Tuggle. "And it just didn't seem very interesting."

Tuggle then thought it would be more interesting if the cop character, named Wes Block, worked on the vice squad and seemed to have some kind of connection with the murderer. Over lunch with a man and a woman from the Los Angeles vice squad, he found his movie. According to Tuggle:

"I said [to the male cop], 'How does being in vice squad and seeing all this sexual stuff all the time affect you?' And this cop said, 'It's made me treat my wife more tenderly in bed.' And it hit me very strongly. I realized that the movie had to be about the connection between the vice squad cop and the serial killer. The cop had some of the same sexual weirdness and desires that the killer did, and the two would mirror each other."

Upon completing his screenplay, Tuggle brought it to "Dirty Harry" director Don Siegel, with whom he'd worked, along with Eastwood, on the hit "Escape from Alcatraz." Siegel told Tuggle to take it to Eastwood, which he did with the stipulation that he would direct the movie. Eastwood acquiesced, but he did have a few requests, the most significant being that Tuggle move the film out of San Francisco, which was too closely associated with the "Dirty Harry" films. Having worked and reveled in New Orleans before, Tuggle thought the Louisiana metropolis would be perfect. Again, Eastwood agreed, so they eventually found themselves in the Big Easy making a cop flick unlike any the star had attempted before.

Clint was in charge, but Tuggle protected the script

It was a somewhat awkward experience for Tuggle, a first-time director working with frequent Eastwood collaborators like cinematographer Bruce Surtees, editor Joel Cox, and casting director Phyllis Huffman. Tuggle said Eastwood was "in charge," but this wasn't a terrible situation considering Tuggle had written a movie where the protagonist at one point oils himself up and beds down nude with a stripper who's been handcuffed to a bedpost.

Tuggle viewed one of his most important roles as being the protector of the screenplay, and he's pleased with how that turned out. "On 'Tightrope,' it was just Clint and me," he said, "And we didn't have any disagreements." If you're thinking a particular artist like Eastwood surely made some changes to the script, you're thinking correctly. He made a change. One solitary change. "The only thing I remember different," said Tuggle, 'The line that always stayed in the screenplay 'I treat my wife more tenderly in bed,' [Eastwood] changed it to 'I treat my wife more tenderly.'" What a meddler.

Tuggle was also pleasantly surprised that Eastwood didn't shy away from what was, in 1984, a potentially thorny scene. It comes when Block is hitting up a queer man for information on the killer, whose victims have a bad habit of having been questioned by Block (or are in the orbit of someone he's encountered). As they're wrapping up, the man gets flirtatious with the detective. When Block says he's not going to a nearby warehouse to avail himself of sexual favors he's ostensibly paid for, the man reads him as a first-timer. "How do you know if you haven't tried it," he asks Block. "Maybe I have," replies the detective.

"It was very brave for Clint to do it," said Tuggle. "He was a little nervous about it [...] Clint went ahead and said that, but I remember he said, 'I'm going to give it another line, too. Because if it looks bad in editing, I don't want to do it. I want to have a substitute.'" Clint didn't need the substitute. While this wouldn't be a big deal today, 40 years ago the notion of the most masculine man in movies suggesting he's had sex with another man had the potential to melt his fanbase all the way down. And it's not just that he says it, it's how he says it, like he's reconsidering in the moment. It's not a classic Clint kiss-off quip. There's something there.

We're all walking that tightrope

This feeling of what mainstream society considered transgression in 1984 lingers throughout "Tightrope," the theme of which Tuggle believes is summed up by a fellow officer giving Block advice on how to handle the case. As she says to Block, "There's a darkness inside all of us, Wes. You, me and the man down the street. Some have it under control, others act it out, the rest of us try to walk the tightrope between the two."

The only tightrope Harry Callahan walks is procedural: should I shoot to kill or wound? As a character, he was a dead end for Eastwood, so Tuggle's screenplay was the perfect departure from and corrective to what he had become. Eastwood speaks fairly plainly about his politics (he's a libertarian), but I think he conveys what's eating at him more eloquently through his movies (heartbreakingly so in his unexpected masterpiece "The Bridges of Madison County"). So I read "Tightrope" as an introspective, bothered, even frightened film from a man whose fans want him to be a snarling badass or a beer-swilling good ol' boy. Eastwood would keep chipping away at this facade for the rest of his career (even in a mind-bogglingly awful dud like "The Rookie"), and I think it's fair to say "Tightrope" is the film that gave him license to wrestle with the essential flaws and hidden shame of the American male.