The Moth In The Silence Of The Lambs Poster Has A Scandalous Secret

In Jonathan Demme's 1991 thriller "The Silence of the Lambs," FBI cadet Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster) finds several interesting and shocking clues while examining a dead body that had been fished out of Elk River in Clay County, West Virginia. Most prominently, large diamond patterns have been sliced out of the skin of the victim's back — though to what end, Starling hasn't yet determined. More curiously, the pathologist finds a cocoon lodged in the victim's throat. It's too delicate to have fallen in accidentally, meaning someone shoved it in there deliberately.

Later, Starling takes the cocoon to a pair of entomologists (Paul Lazar and Dan Butler), hoping to learn more about it. The entomologists carefully dissect the cocoon and find it to be the species acherontia styx, better known as the death head moth (although it should have been more accurately described as the lesser death's head hawkmoth). The insect is easily recognizable, as it bears a curious white blotch on its thorax that resembles a human skull.

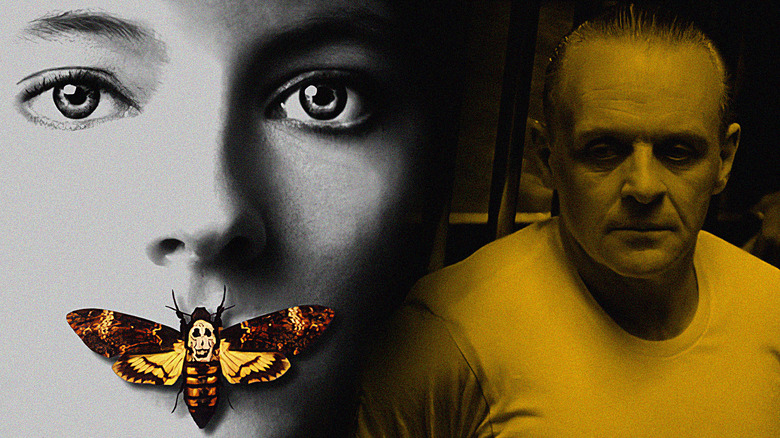

The moth was such a striking element of "The Silence of the Lambs" that the film's marketing department put it on posters, often with its wings spread over the mouths of Starling or of Hannibal Lecter (Anthony Hopkins), the intelligent and imprisoned serial killer whom Starling consults for advice into the minds of other killers.

Looking close at the poster, however, one might find that the death head moth isn't the same as the one seen in the movie. Indeed, the skull on the poster is actually a famous photograph conceived by Salvador Dalí and taken by fellow surrealist Philippe Halsman, wherein they arranged several unclothed women in an outsized skull-shaped tableau.

The hidden Salvador Dalí photo in the Silence of the Lambs poster

A close look reveals the moth's thorax skull to be "In Voluptas Mors" ("voluptuous death"), Dalí and Halsman's famed 1951 photograph. Seven women were asked to model on a special platform, arranged by Dalí into a skull. The teeth of the skull are the women's feet, and its nose is formed between two of the models' hips. One model is curled up at the bottom, forming its lower jaw, and two standing models form its cheekbones. A woman in the center holds her arms out, her torso and arms forming the skull's forehead and eyebrows, while a seventh model curls up at the top, forming the head. The Huffington Post once published several behind-the-scenes photos of Dalí arranging the models for Halsman. Sadly, the models are not identified by name. The shoot took about three hours, which is a long time to kneel awkwardly on a pedestal.

The image had to be slightly tweaked for the "Silence of the Lambs" poster to take the most explicit details out. "I had to paint some stuff out of it because MPAA requirements were not to have any nudity," designer Dawn Baillie explained in a discussion with Poster House. "So that had to be a little fudged."

Dalí liked to mix the necrotic and the erotic, surreally blending the sensual with death. Dalí's paintings saw human bodies stretched and distorted into vague, mutated dream figures, as they might appear unfiltered from the unconscious. Dalí and Halsman famously collaborated on multiple pieces, including a book's worth of photos, published in 1954 as "Dalí's Mustache." You might be familiar with the 1948 photo "Dalí Atomicus," wherein Dalí, a painting a chair, a splash of water, and three housecats were all seemingly suspended in midair.

Halsman was also an accomplished portrait photographer in his own right. The portrait of Albert Einstein seen on a U.S. Postage stamp was snapped by him, and the same portrait was famously used on the cover of Time Magazine 33 years later. He also took pictures of the Marx Brothers, Richard Nixon, Marilyn Monroe, Milton Berle, and Sid Caesar.

What kind of moth is in The Silence of the Lambs?

As mentioned, the moth is slightly misidentified in "The Silence of the Lambs." The entomologists Pilcher and Roden carefully slice open the cocoon's carapace and call it the death head moth. In reality, the lesser death's head hawkmoth isn't as horrifying as its name would lead one to believe. The hawkmoth is actually fond of fruits and honey, and has the unique ability to excrete an odor that resembles that of bees. Using the scent as camouflage, the moths infiltrate beehives to steal honey. Although, it seems that the scent isn't a foolproof defensive measure; death's dead hawkmoths have been found dead inside beehives after being killed by guards.

Hawkmoths possess thick, pointed tongues that allow them to puncture honeycombs and suck the honey out from inside. They also use their tongues to puncture the skin of fruit, making them a pest to the growers of yuzu in Korea; moth tongueholes can ruin a nice citrus.

One of the plot points of "The Silence of the Lambs" is that the death's head hawkmoth isn't local to the United States, giving the FBI an investigative advantage. If the killer, Buffalo Bill (Ted Levine) is cultivating moths, he would need the caterpillars imported from overseas. Indeed, Jack Crawford (Scott Glenn) thinks he has the drop on Buffalo Bill when he finds an invoice for live insects from Suriname. They are most commonly seen, however, in China, Malaysia, Japan, Thailand, and Vietnam.

The moth on the poster for "The Silence of the Lambs" is not an acherontia styx like in the film itself, but a different subspecies, acherontia atropos, the African death's head hawkmoth. Atropos are larger, and live throughout the entire African continent.

How Silence of the Lambs created the iconic moths

According to the website Bug Under Glass, many of the adult death's head hawkmoths were real, wrangled by famed Hollywood bug wrangler Ray Mendez. Film buffs may recognize Mendez as one of the four subjects in Errol Morris' 1997 documentary "Fast, Cheap & Out of Control" wherein he spoke at length about naked mole rats. Mendez also helped wrangle the cockroaches for the famously creepy infestation portion of George A. Romero's "Creepshow" in 1982, as well as the cockroaches for the raunchy 1996 MTV musical "Joe's Apartment." He also handled the bees for the 1989 drama "Signs of Life," and helped design the bug-like monster for the 1983 monster flick "Spasms." Mendez knows his bugs.

The closeups of the fully-grown living insects, notably the one wherein a moth lands on Buffalo Bill's textiles, were all the real deal. The cocoons and pupae, however, were not death's head moths, but tobacco hookworms. Perhaps the filmmakers didn't think the death's head hawkmoths looked quite right, and decided on a more cinematic insect instead. Or maybe it was difficult to obtain cocoons and pupae of hawkmoths in the United States, where "The Silence of the Lambs" filmed.

What is the significance of the moth in Silence of the Lambs?

"The Silences of the Lambs" is an excellent movie, and it was immensely popular, but it has always been horribly transphobic. Buffalo Bill kidnaps and murders women, and removes portions of their skin, hoping to make a full-body female suit to wear. Bill — real name: Jame Gumb — dances to himself in a famous sequence, and tucks his member between his legs, hoping to appear more female.

Hannibal Lecter explains that the moth symbolizes chance. Gumb is becoming a new person. A new woman. She is about to come out of her cocoon.

Lecter has a condescending line late in the film, however, where he explains that Gumb isn't transgender, "he only thinks he is." Lecter says that a childhood of abuse and constant trauma manifested as gender dysphoria, when all Gumb really wants is to kill and to possess the women around him. Lecter conveniently ignores the fact that Gumb sought gender reassignment surgery for the better part of a decade, a subplot that was explored more fully in several deleted scenes (featuring Roger Corman!). "Lambs" fed into a bleak, transphobic stereotype about murderous trans people that fed into a general sense of cultural bigotry that lingers to this day.

"Lambs" was always criticized for its transphobia, so its legacy is complicated. On one hand, it's a progressive feminist parable about women taking back their agency. On another, it's a horror story about trans-ness and its assumed evil.

The macabre moth motif, explained

Moths, of course, have always been associated with death and decay. Indeed, one might be familiar with the phrase "macabre moth" to describe the symbolism attached to the animal. Moths are essentially seen as the "evil twins" of butterflies, as butterflies tend to be colorful, dainty, and bound to placid, verdant gardens. Moths are gray and brown, with thick, creepy bodies, typically found in closets and cabinets. Moths, then, are associated with shadows, dankness, and decay. Indeed, it's telling that biologists chose to give the insects names like "death's head moth" and "black witch moth." The little flitting critters simply look odd, like chubby little dudes wearing cultist's robes.

Edgar Allan Poe famously described a moth monster in his short story "The Sphinx," said to be a human-sized insect with a human skull. As the narrator approaches the creature, though, it turns out to be an ordinary moth. Anyone who has found a huge moth in their closet has likely experienced the same emotional roller coaster as that narrator.

Numerous films use moths to indicate horror. Once might recall the moths in Guillermo del Toro's "Crimson Peak," or the moths that surround the creepy demonic ghost in "Mama." And, of course, denizens of West Virginia may have personally met the Mothman, the world's coolest cryptid. (Even though he is said to have caused a bridge collapse in 1967.)