Batman: The Animated Series Inspired This Classic Anime From Cowboy Bebop's Creators

"Batman: The Animated Series" was created at Warner Bros. Animation by and for an American audience. As is common practice in American cartoons, though, the animation work was outsourced to studios in southeast Asia.

One of those subcontractors was Japan's Sunrise, the home of the "Gundam" franchise and the studio that would go on to make "Cowboy Bebop." One of the most famous and well-regarded studios in Japan, Sunrise (officially known as Bandai Namco Filmworks these days) is where several animators (such as the founders of Studio Bones) first built their careers.

Sunrise handled seven episodes of "Batman: The Animated Series" — "Pretty Poison," "The Cat and the Claw, Part I," "Heart of Steel," "I Am the Night," "The Clock King," "Off Balance," and "The Man Who Killed Batman." Sunrise itself is divided up into several smaller studios; "Batman" was handled by Studio 6. The experience apparently left an impact, though, since one of Sunrise Studio 6's later, in-house projects, "The Big O," owes a lot to "Batman: The Animated Series."

"The Big O" was created by Hajime Yatate (a collective pseudonym used by Sunrise staff), series director Kazuyoshi Katayama, and Keiichi Sato. Sato (who is still working in anime today, having recently directed 2024's "Super Sentai" parody "Go Go Loser Ranger") was the one who first conceived the idea; he wanted to make a giant robot show that would appeal to American audiences (and hopefully sell some toys). Hence, an anime that looked like one of America's favorite cartoons.

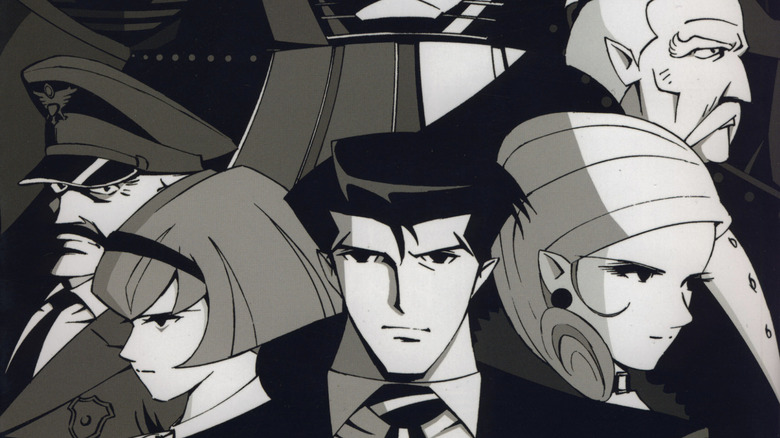

The show is set in Paradigm City, a New York-esque metropolis and seemingly the last holdout for humanity after an apocalyptic event. None of Paradigm's people can remember earlier than 40 years ago, and this loss of memory overshadow the series. The lead is Roger Smith, a professional negotiator who, when he can't solve problems with his silver tongue, jumps in a "megadeus" mecha called the Big O.

How The Big O homages Batman

In the 25 years since "The Big O" premiered, it's commonly been described as "What if Batman had a mecha?" Jason DeMarco, co-creator of Cartoon Network programming block Toonami (where "The Big O" premiered stateside and exploded in popularity), also compared the series' animation style to "Batman: The Animated Series."

Roger Smith himself is based on Bruce Wayne — a well-dressed man who rides in a sleek black car and investigates strange happenings or bad actors working in the city. When it's time to fight, Bruce/Roger changes into his other self. In an interview with Anime Play magazine, Sato once admitted the influence of Batman on "The Big O." Writer Chiaki J. Konaka also cited both Batman and Dick Tracy as influences.

As for the mid-century New York, half urban noir, half art deco look of Paradigm City? "I did have Manhattan and stuff in mind but felt if we specified the location we would be bound to and restricted by reality," Sato said, so better to make a fictional location. That, right there is basically the ethos of Gotham City too; it is simultaneously every city in America and none of them. In "Batman: The Animated Series," Gotham City looked more like a 1930s metropolis than a 1990s one, adding to the timeless feel that "The Big O" shares.

Roger's supporting cast is quite Batman-esque too. Most obviously, he has a butler (Norman Burg) who is his closest confidant and helps him maintain his equipment. The only difference between Norman and Alfred Pennyworth is that the former has an eyepatch. Roger's other partner is R. Dororthy Wainwright, an android girl made in the image of her creator's late daughter. (Konaka claims credit for designing and characterizing Dorothy beyond "Roger's android sidekick.") While she dresses like a red-headed Wednesday Addams, Dorothy is Roger's Robin: a vulnerable orphan adopted by the hero who becomes his partner.

Roger has a special relationship with police Major Dan Dustan, like Batman's with Commissioner Gordon, and often crosses paths with an enigmatic blonde named Angel, who is half Catwoman, half Faye Valentine from "Cowboy Bebop," another femme fatale with memory problems. Cementing the comparison, both Faye and Angel were dubbed by Wendee Lee in English.

Paradigm City faces not only villains of the week, but Roger's small rogues gallery as well: hapless gangster Jason Beck, the twisted former journalist Schwarzwald/Michael Seebach (whose mask of bandages resembles the Scarecrow), and the sadistic cyborg Alan Gabriel (who has a pale white face and smile that could easily fit on the Joker).

The Big O anime dresses tokusatsu with film noir

Konaka said "The Big O" staff was "keenly interested in how Americans view the series." When it premiered on Toonami, it was a hit. I think one can easily compare it to how "Cowboy Bebop" caught on hard among English-speaking audiences thanks to its American style. "The Big O" has a jazz-inspired score (composed by Toshihiko Sahashi), similar to Yoko Kanno's "Cowboy Bebop" music, and the two series shared some dub voice actors. (Aside from the aforementioned Mrs. Lee, Roger is voiced in the "Big O" English dub by Spike Spiegel himself, Steve Blum.)

In fact, Toonami saved "The Big O." The show's episode count was cut from 26 to 13, but after it premiered in America, Cartoon Network stepped in to co-produce a second season (aired in 2003, three years after season 1 ended). However, the series' new sponsor had a request to keep the series from becoming too "esoteric." In DeMarco's words, "You don't have to explain WHY everything is happening, but you do have to make it clear WHAT is happening." The Japanese staff evidently took that to mean "focus more on the mystery of Paradigm City," and how/why everyone lost their memories.

"The Big O" experiences a shift from episodic to serialized storytelling across its two seasons. The early episodes are all standalone, focused on Roger and Dorothy handling individual cases, like a kidnapping or an unresolved murder. Something is wrong with Paradigm but it's above our heroes' paygrade to find out. In an interview published in the "Big O" art book, Konaka said he saw Roger as being like Josef K. in Franz Kafka's "The Trial," a story about a man being prosecuted without being told what he's on trial for. The post-apocalyptic world of Paradigm City, such as the domes incorporated into the city-scape, was (per the art book) Katayama's idea to make the city feel less like a straight copy-and-paste of Gotham City.

These episodes of "The Big O" are where more of the Japanese TV influence comes in; the climax is invariably Roger hopping into the Big O and fighting a giant robot or monster. "The Big O" looked like a Batman cartoon but unfolded like a tokusatsu series. Then the second season (written entirely by Konaka) became more about the mystery.

How The Big O changed from season 1 to season 2

Konaka is famous for surreal storytelling inspired by H.P. Lovecraft (see: "Serial Experiments Lain.") "The Big O" season 2 was no different; it ultimately spread its wings into metatext, suggesting Paradigm City was a fictional world with all its inhabitants playing assigned roles. They couldn't remember earlier than 40 years prior because they hadn't existed 40 years prior. One can infer (from repeated dreams Roger has of megadei like the Big O setting a city ablaze) that the robots are leftover weapons from the war that destroyed the world.

Through this shift, "The Big O" underlined themes about memory and how it is the fabric of identity. In the artbook, Katayama compares the story to science-fiction writer Philip K. Dick, author of "Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?" (adapted into "Blade Runner"), "We Can Remember It for You Wholesale" (better known as "Total Recall"), and many more. Like Rick Deckard and Doug Quail/Quaid, Roger is left uncertain if he and/or his reality are genuine but still chooses to live as if they are.

In "The Big O" staff interviews, they frequently compare the series to the 1995 anime "Neon Genesis Evangelion." (Indeed, Dorothy has been compared to Rei Ayanami from "Evangelion" — she too is a pale, emotionless, not totally human girl with a bob haircut.)

To this day, it's impossible to make a mecha anime and not be compared to "Evangelion," but "The Big O" isn't similar only because of its giant robots. Both shows begin as more "normal," with a monster-of-the-week structure, then get weirder towards the back half of their 26 episode run. By the end, both "Evangelion" and "The Big O" are tearing apart the foundations of their characters' reality.

Frankly, I do have a softer spot for the standalone mystery episodes of "The Big O" season 1. I find they share another strength of "Batman: The Animated Series," where episodes often felt like short and sweet noir films. I wasn't disappointed to see the series explore its underpinning more, but I did miss the more varied storytelling of season 1. Batman may be the World's Greatest Detective, but I think even he'd agree some tantalizing mysteries are better left unsolved.