What Every Single Hellboy Movie Has Been Missing

"Hellboy: The Crooked Man" is the second movie reboot of the demonic superhero, this time played by Jack Kesy. Hellboy was created by writer/artist Mike Mignola in 1993 and has since starred in countless comics published at Dark Horse. A demon named Anung Un Rama, Hellboy was summoned to Earth in the final days of World War II by the Nazi operation Project Ragna Rok. Instead of becoming the Third Reich's ultimate weapon, however, he was adopted by the American Bureau of Paranormal Research and Defense (B.P.R.D.) and is the Bureau's top agent.

Hellboy is half a fantasy pulp hero, half a procedural detective; most of his stories are short and small-scale, and he faces supernatural horrors with the same attitude an exterminator does a wasp nest. "The Crooked Man" — following Hellboy fighting a sadistic ghost in the Appalachian mountains — looks like it had some good ideas. The comic story (drawn by Richard Corben) is beloved. The small scale horror vibes? That's not just a matter of budget, it's what most "Hellboy" comics are like. The series' trade paperbacks include intros for each story, written by Mignola, where he explains how he came across or read some piece of folklore and decided to draw a comic that threw Hellboy into that fable.

But the film's production has sent up flags as red as Hellboy's flesh. Director Brian Taylor ("Jonah Hex," "Ghost Rider: Spirit of Vengeance") does not have an inspiring resume. Meanwhile, "The Crooked Man" trailers have earned many comparisons to YouTube fan-films, with the Syfy movie color grading not helping; the film looked cheap, not restrained.

We also recently learned that "Hellboy: The Crooked Man" will be skipping theatrical distribution in the U.S. and instead releasing via video-on-demand come October 8. With all these warning signs, fans are once again shouting that they want Guillermo del Toro's "Hellboy 3." I do too, but it does rub me the wrong way when people suggest Hellboy belongs to del Toro or that the character was only ever good when del Toro was handling him. Mignola's comics are brilliant and none of the "Hellboy" films have quite reached their bar.

No Hellboy movie is as good as Mike Mignola's comics

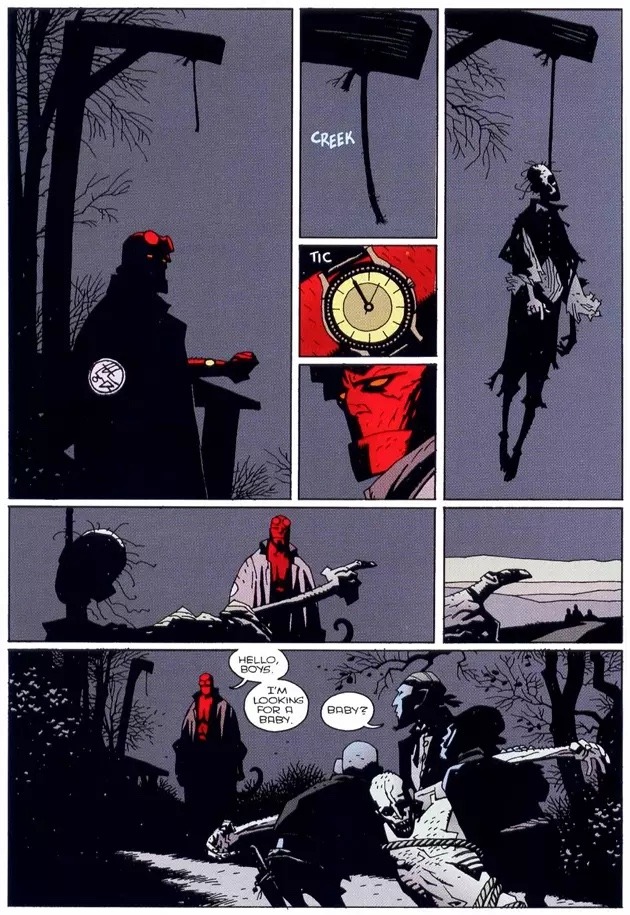

Hellboy is inextricable from Mignola's art style, which I'd call "Gothic minimalism." His drawings often have one-to-two color backgrounds; detailed subjects are enclosed in negative space. Those compositions, mixed with heavy black shading and stark divides in the color palette, make it seem like the characters are peeking out of real darkness. Hellboy's bright red coloring stands out all the more against the black backgrounds Mignola places him in.

As for his characters; Mignola likes to draw statues, and gothic figures, stone grotesques, and tombstones are frequent imagery in his work. You can see that affinity in how he draws living characters too. His monsters look like they were carved from granite or marble; think Hellboy's square jaw and stone-like skin texture.

Mignola's genius comes through not just how he draws his comics, but how he paces them. Older comics (the kind Mignola might have read as a kid) tend to move much faster. They'd cram as much story into 20 pages as they could, and each panel would jump to something new. But as part of that cramming, they'd often stuff in wordy textboxes, crowding the flow. The comic storytelling mode currently in fashion is "decompression," where scenes play out longer (some pages will feature a sequence of unchanged panels, with only the dialogue moving). The downside is slower pacing, where individual issues can feel inconsequential, needing to be read as part of a whole.

Decompression is meant to make comics more cinematic, but Mignola's books strike that rhythm moreso than any other I've read. Whenever he moves to a new panel, it's to show something new. However, he also doesn't get bogged down in dialogue. As you read, you soak up the atmosphere of the art without the story feeling empty like the worst decompressed comics can.

As an artist turned writer, Mignola knows how to pace a comic story just right and let his drawings speak for themselves. Whenever I flip through the pages of a "Hellboy" comic, I'm in awe.

Hellboy is comic book mythology like no other

Mignola is a voracious reader. His favorite characters include Dracula and Conan the Barbarian — unsurprising since "Hellboy" melds horror and adventure. His willingness to dive into obscure ghost stories and pull out settings for his comics is how the world of "Hellboy" feels unique and ever evolving. Reading a "Hellboy" comic often feels like sitting by a campfire as your pal is making you shiver with some great ghost stories. ("Hellboy" stands as an essential lesson that to make great comics, comic writers and artists need to read more than just other comics.)

Hellboy goes on globe-trotting adventures because everywhere in this world has unique folklore and ghost stories. Take one of the most famous Hellboy short stories, "The Corpse" — to save an infant abducted by Irish fairies, Hellboy must agree to bury a talking corpse in a Christian burial ground by sunrise. The task, which is more difficult than it sounds, is right out of an old fable (think the many stories of trolls asking riddles) more so than a superhero comic, and with good reason; "The Corpse" based on a story by Sir Douglas Hyde.

"The Crooked Man," as both a comic and film, is Appalachian horror in the vein of "The Night of the Hunter." Hellboy's greatest foes include the Baba Yaga (a Slavic witch famed for living in a walking house), Nimue the Blood Queen (King Arthur's the Lady in the Lake), and the Ogdru Jahad, the reptilian root of all evil. The Ogdru Jahad is no generic lord of darkness, though; they are explicitly meant to be the biblical Dragon of Revelation, seven heads and all. Hellboy's fiery crown, which sparks when he gives into his apocalyptic destiny, likewise echoes that "Book of Revelation" passage about the world-destroying beast.

The "Hellboy" comic "The Wild Hunt" reveals that, though his human mother, Hellboy is a descendant of King Arthur. This is the ultimate example of Mignola twisting real myths to make his own. Hellboy's lineage, both artistically and within the text, goes back to the original mythic hero of human civilization. The fact that Anung Un Rama descends not only from demons, but from a classical hero too, further illuminates the divide between how he was created to be evil yet always chooses to be good instead.

Since "Hellboy" is unserialized, but more like a collection of overlapping short stories, it's the only American superhero comic that truly balances a long-running mythology with the once golden rule: "Every comic can be someone's first."

Guillermo del Toro's Hellboy movies are good, but unlike the comics

I intend absolutely no shade at Guillermo del Toro. He's one of my favorite filmmakers and his "Hellboy" movies are great. They were my introduction to the character and "Hellboy II: The Golden Army" holds up as one of the superhero genre's best films. Ron Perlman is perfectly cast as Hellboy too; his is the voice I hear when I read Hellboy's dialogue in Mignola's comics. But as I read those comics, I realized just how different del Toro's films are. The best comparison is Tim Burton's Batman movies; compelling works of pop art, but one where the director draws from their own personal ethos rather than adapting the source material's spirit.

That's not to say del Toro dislikes Mignola's Hellboy or arrogantly thought he could do better. No, his changes come from a place of love. In his glowing foreword to "Hellboy" volume 5 ("Conqueror Worm"), del Toro calls Mignola "a genius" and "a comic-book demi-God." "I humbly confess that many a time I have aspired to imitate Mignola's mysterious style in the design of my films, especially the cold, velvet blacktop of darkness from which his characters emerge," del Toro wrote.

The director claims that Mignola's "hyper-expressionistic lighting" turned out to be "almost impossible to reproduce in a 3-D world," but the first 2004 "Hellboy" film makes a good go of it. The film sticks fairly close to the first "Hellboy" story, "Seed of Destruction." As del Toro is also an admitted fan of "The Corpse," there's a scene in "Hellboy" where Hellboy carries a mangled zombie on his back like in that short story. "The Corpse" ends with the fairies lamenting how they're slowly vanishing from the world, which feels like the seed for "Hellboy II: The Golden Army." That movie, otherwise a completely original story, is about environmentalist Elf Prince Nuada (Luke Goss) trying to wipe out humanity to save the Earth for magical creatures. Pulling from real Gaelic myths, "The Golden Army" looks to the same places for inspiration that "Hellboy" comics do.

The shadowed cinematography of the first "Hellboy," though, gives way to brighter warm tones in "The Golden Army." This is the key difference in the movies' mood compared to the comics. As a filmmaker, del Toro is an unabashed romantic who wears his heart on his sleeve. He hooks up Hellboy and fire-starting B.P.R.D. agent Liz Sherman (Selma Blair), a purely professional friendship in the comics. Hellboy's relationship with his adopted father Professor Trevor Broom (John Hurt) is also explored more in the movie and Broom's death is a lot more impactful. In "Seed of Destruction," Broom dies only to kick off the story.

Then there's a major change del Toro makes to Hellboy's history.

How Guillermo del Toro's films changed the Hellboy comics

In Mignola's comics, Hellboy's existence has been public knowledge since the 1950s, almost his entire adult life. No-one bats an eye at him whenever he walks down the street, and the B.P.R.D. is a public monster-hunting service like the Ghostbusters. In del Toro's Hellboy movies, however, the B.P.R.D. is a secret organization and Hellboy's existence is concealed.

Perlman's Hellboy often acts like an angsty, headstrong teen; he wants to be part of the world he's sworn to protect, but he's forbidden to. In a vulnerable moment, he admits to Liz he wishes he could "do something" about his inhuman face for her. When Hellboy's existence is revealed to the world in "The Golden Army," he's shunned. Even if the human world knows about him, he can't be part of it. No surprise there; del Toro loves monstrous-looking outsiders (see: "The Shape of Water" and his upcoming "Frankenstein") and he remolded Hellboy in that vein.

Mignola, though, based Hellboy on his father. Mignola's dad was a blue-collar carpenter and World War II veteran whose stoic shell never cracked, even as he told his sons chilling stories of the war or workplace accidents. Hellboy's enormous Right Hand of Doom was inspired by the huge, beaten-up hands that Mignola Sr. got from a lifetime spent building cabinets. Mignola's Hellboy does not have the impetuous streak or short temper that del Toro and Perlman's does; he's got a gruff, unbreakable calm because when you live a life as weird as he does, nothing phases you. The "Hellboy" comics are out to thrill you and sometimes creep you out, not out to tug at your heartstrings like del Toro's films are. Mignola even believed he could never write a scene that would make someone cry.

In the documentary "Mike Mignola: Drawing Monsters," Mignola recalls, "I lost all the battles I fought on 'Hellboy II.'" In the doc, Mignola is described as a particular (and often short-tempered) artist who knows what he wants and demands it from his collaborators. Mignola has been fairly magnanimous when talking about the creative liberties del Toro took, but he also stresses a hard line between his Hellboy and the movie version as fundamentally different.

I get it, not every cinephile is also a comic reader. So if you only know Hellboy from the movies, then you're going to associate the good versions with del Toro. But Hellboy is not del Toro's character, he's Mignola's. While I like del Toro's movies, I sympathize with Mignola wanting "Hellboy" films that are closer to his comics. The problem, though, has been the execution.

The 2019 Hellboy reeks of wasted potential

Oh, "Hellboy" (2019), what went wrong? (Quite a lot behind-the-scenes.) On paper, it had so much going for it. Neil Marshall was a good choice to direct, and David Harbour was well cast as Hellboy. (His performance is the movie's best part). It also adapts one of the best "Hellboy" stories, what I'll call the Blood Queen trilogy. Written by Mignola, drawn by Duncan Fegredo (whose art is as close to Mignola as you can get aside from the man himself — see below), and colored by Dave Stewart, these three comics — "Darkness Calls," "The Wild Hunt," and "The Storm and the Fury" — feature Hellboy finally facing the apocalypse he's tried so hard to put off.

The movie also works in "The Corpse," solely to establish the backstory of Alice Monaghan (Sasha Lane), the baby Hellboy saved, and Gruagach (Stephen Graham), the pig fae who Hellboy defeated. Harbour's "Hellboy" is introduced in a sequence adapting "Hellboy in Mexico," where Hellboy sadly has to kill his friend Esteban, who became a vampire.

In Mignola's comics, Hellboy's internal conflict has always been less that he feels alone and more that he's destined to destroy the world but doesn't want to. At the end of the story "Box Full of Evil," he observes that he's spent his life killing demons who think him their savior. That is meant to be the movie's throughline and Hellboy's arc; from killing Esteban to Nimue (Milla Jovovich) tempting him to rule by her side, Hellboy must contemplate if he would be better off submitting to his evil nature and creating a world for creatures like him.

But it doesn't work. Even with a two hour run time, the movie feels rushed. It feels less like an exploration of Mignola's world and more like a slideshow of it. As with its fellow worst superhero movies, watching "Hellboy" makes you feel like someone is upselling you a cinematic universe.

The story beats of the comics are there, but not the mood. Harbour's Hellboy still isn't the steely hero of the comics, but is instead even more immature than Perlman's and makes wisecracks too groan-inducing for even Deadpool. The three parts of the Blood Queen trilogy also have distinctive themes and aesthetics. "Darkness Calls" is centered on Russian folklore, "The Wild Hunt" is about Arthurian legends, and "The Storm and The Fury" is the Book of Revelation. In the film, all of this blurs together.

The film's visuals and monster designs have neither the majesty of Mignola or del Toro, looking instead like generic blockbuster mush. I have not seen "Hellboy: The Crooked Man" yet, but the visuals don't seem like an improvement over the 2019 "Hellboy."

The world Mignola has written could easily sustain a blockbuster franchise (and I think it's pretty clear he wants it to), but the last two attempts have just not been it. Maybe del Toro was right, and trying to capture the style and spirit of Mignola's comics on film is a doomed prospect. I think Hellboy would be a ripe fit for animation instead. There were two animated films (featuring the del Toro movies' cast) made in the 2000s: "Sword of Storms" (set in Japan, expanding "Hellboy" short story "Heads" to feature length) and "Blood and Iron" (a semi-adaptation of the second big Hellboy story, "Wake the Devil"). The comics' episodic storytelling, though, lends itself to a full-blown cartoon series.

But for now, if you want to experience Hellboy in his truest form, there's the evergreen advice nerds like me always spout: read the comics.

"Hellboy" is available across several collected editions, including a 12 volumes paperback series (featuring two extra volumes for the finale "Hellboy in Hell" series), a four volume paperback omnibus series, a seven volume "library edition" hardcover series, and an 1500+ "Monster-Sized Hellboy" omnibus edition.