Alien: Romulus Isn't Based On The '90s Dark Horse Comics – But It Sure Feels Like It

This article contains mild spoilers for "Alien: Romulus."

Despite being around for 45 years, the Xenomorph and the "Alien" franchise have never completely lost its unique quality. Instead of an endless glut of sequels, remakes, reboots, and other assorted franchise-exhausting traps that have happened to many other great series, "Alien" has always been treated with a degree of respect. The film series is remarkably filmmaker-driven, with each successive director bringing their own sensibilities and interests to their installments without worry about some rigid narrative canon or house style. The Alien is a mutating, consistently surprising organism, and the franchise has been allowed to change along with it.

This idea-first approach has extended to the franchise's tie-in material, be it novels like "Aliens: Original Sin" or video games like "Alien: Isolation." That game in particular was initially rumored to be a large influence on the latest cinematic iteration of the Xenomorph: Fede Alvarez's "Alien: Romulus." While Alvarez has been vocal about his love of the video game and the easter eggs in "Romulus" that pay homage to it, his film is not at all an adaptation of the game; Rain (Cailee Spaeny) is not revealed as Amanda Ripley, in other words.

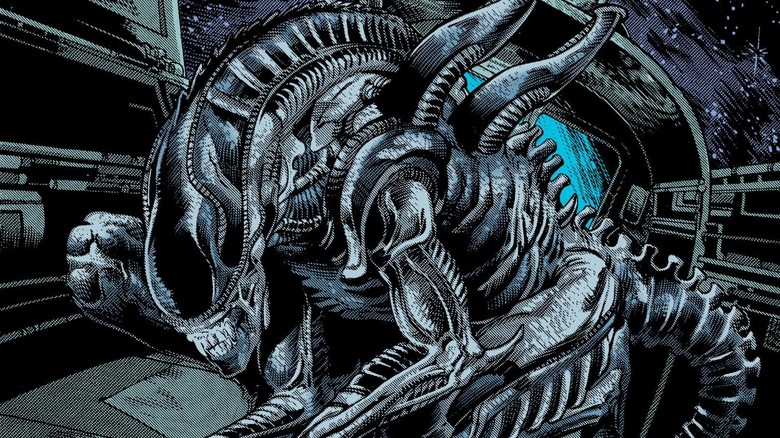

"Romulus" is instead a deliberate smorgasbord of the entire "Alien" franchise to date, making either references or concrete ties to just about every movie in the series. It also, like its "Isolation" Easter eggs, takes into account some ancillary material. This is why "Romulus" feels especially like a big-screen version of the various Dark Horse Comics tie-in series from the late '80s and '90s. While none of these comics are strictly canon, they introduced some great concepts to the "Alien" lore, and at least one of these happily shows up in "Romulus."

Romulus is a very comics-style sequel

The idea of licensed comic book adaptations, where characters established in another medium make their way to comic strips and books, has been around almost as long as cinema itself. In addition to famous literary characters like Sherlock Holmes and Tarzan, there were newspaper strips adapted from Charlie Chaplin's Tramp character around the time of the First World War. In this tradition, most early comic adaptations were taken as alternative adventures of the same screen characters you know and love; the Gold Key "Star Trek" comics, for instance, featured further missions of Kirk, Spock, and Bones, the "Star Wars" comics published by Marvel in the late '70s continued the quest of Luke, Han, and Leia to topple the Empire, and so on.

Initially, in a time before film franchises became commonplace, these comics and other tie-in material were the de facto sequels. However, once movie sequels proved to be lucrative for studios, these stories naturally started to become de-canonized, meaning fan interest could wane as a result. To try and keep that from happening, tie-in comics started to explore other characters or even created new ones so that their stories wouldn't necessarily clash with the main canon of the films.

Thus, the concept of the "sidequel" was born, stories that aren't sequels in the strictest sense (i.e. they don't feature the protagonists from the "main" storyline) yet are set during a particular point in the series timeline. Although there now exist several examples of this in film franchises, comics certainly helped popularize the concept. Thus, "Alien: Romulus," set between "Alien" and "Aliens" but featuring elements or references from the prequels and sequels, feels very comics-inspired, as it's the type of storytelling the Dark Horse comics tended to do during their heyday.

Taking a page from comics allows Romulus to create while avoiding future traps

The Dark Horse "Aliens" line was not structured like most tie-in comic books. Instead of a single ongoing series, the editors of the company chose to publish a variety of limited series and one-shots, thereby allowing for a maximum amount of creativity from a variety of writers and artists. This plan indeed allowed some wild ideas to thrive, chief among them the notion of a Synthetic Xenomorph, Jeri, as seen in John Arcudi and Doug Mahnke's "Aliens: Stronghold."

Although Dark Horse planned out their approach to "Aliens" early on, they didn't completely avoid the trap of canon and continuity. Their very first miniseries, simply titled "Aliens" and published from 1988-1989, was written by Mark Verheiden and illustrated by Mark A. Nelson, and followed an adult Newt and an older Hicks from "Aliens." The appearance of Ripley was held back from Verheiden and Nelson's first two "Aliens" miniseries, only for her to make a triumphant appearance in their third and final entry, "Aliens: Earth War." That third series was published in 1990, and two years later, "Alien 3" was released, revealing the deadly fates of all three of those characters. Thus, Dark Horse went back and republished those initial three miniseries with the names of the characters changed (and Ripley's presence turned into a synthetic version of the woman).

As of now, the "Alien" film franchise isn't quite a closed loop; there has yet to be a sequel to the events of "Alien: Resurrection" (although there have been a few in the comics and novels), and the fate of David the synthetic from "Alien: Covenant" is still anyone's guess. The new characters and environments of "Romulus" allow it and potential future movies to have a path forward until (or unless) someone comes along to pick up the thread of those other characters.

Romulus makes a concept from the comics officially canon

In both "Alien" and "Aliens," Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) defeats the Xenomorph and the Queen Alien (respectively) by chucking them into the depths of outer space, an environment known to be inhospitable to most forms of organic life. Yet, as established in Verheiden and Nelson's initial "Aliens" miniseries (later retitled "Aliens: Book One" and "Aliens: Outbreak"), it seems the Xenomorph has a natural immunity to such a place, and can survive in space indefinitely. It's a horrific plot twist very much in keeping with the bleak, nightmarish aspects of the creature, taking what seemed initially like a clear victory at the end of those films and twisting it around.

In "Romulus," the Weyland-Yutani corporation goes to much trouble to retrieve what they think is the decaying corpse of the Xenomorph that Ripley blew into space off the Narcissus escape shuttle, only to discover that it was not quite dead after all. By the time Rain and her compatriots board the abandoned Romulus and Remus twin space station, that Alien has since been defeated, but at a cost, having spilled its acidic innards and blown a hole in much of the station. What's more, its DNA was used by the synthetic science officer Rook (Ian Holm and Daniel Betts) to perform a variety of experiments to get at the secret of their biology, which involved genetically engineering a new slew of facehuggers, thus causing a full-blown outbreak on board the station.

Seeing as how "Romulus" is a film that, even more than "Alien: Covenant," bridges the gaps between every "Alien" movie (with the possible exception of the "AvP" films, those being actual Dark Horse Comics adaptations), it's fitting that it takes at least one key concept from the comics and brings it into the films. In every way, "Alien" lives!

"Alien: Romulus" is in theaters everywhere.