Leonard Nimoy's Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home Vision Centered On 6 Rules

It has been written in the pages of /Film in the past (by yours truly) that "Star Trek" excels when it eschews the boring tropes of action thrillers in favor of philosophy, diplomacy, crisis, teamwork, and character. Action movies demand that heroes use violence to solve their problems, and most of the films in the genre climax with a fistfight, a shootout, or a chase. Often, the hero will even go so far as to murder the villain. Action movies use fake violence as a simple solution to complex problems. How easy it would make things if kicking a man off a cliff repaired the world's ills!

"Star Trek," at least to my mind, has always served as an important counterpoint to action-forward thinking. Yes, plenty of "Star Trek" stories (especially the 13 movies) end with an explosion and/or the murder of the villain, but it has always been truer to its principles when it solves its problems with diplomacy and heroism.

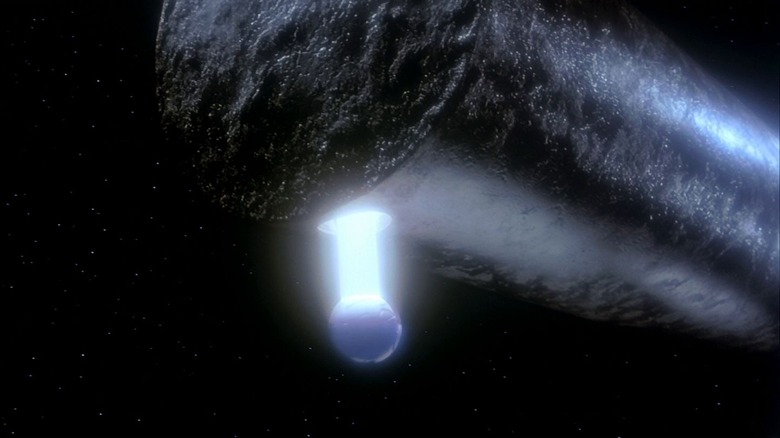

Case in point: "Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home." That film was the highest-grossing "Star Trek" film from 1986 until 2009, and it features no villains, no action sequences, no gunfights, no fistfights, and no car chases. The story, for those unfamiliar, involves a mysterious probe that unexpectedly begins draining Earth's oceans, looking for humpback whales, hunted to extinction many years before. The Enterprise crew, using a repurposed Klingon ship, travel back in time to 1986 to rescue a pair of whales and bring them back to the 23rd century to deflect the probe.

According to the 1995 book "The Art of Star Trek" by Judith and Garfield Reeves-Stevens, director Leonard Nimoy had a distinct anti-action policy for "Voyage Home," and expressly forbade six action-forward concepts for his screenplay.

The six anti-action mandates

In the book, Nimoy said that he wanted his film to lack the following:

"No dying, no fighting, no shooting, no photon torpedoes, no phaser blasts, no stereotypical bad guy. I wanted people to really have a great time watching this film [and] if somewhere in the mix we lobbed a couple of big ideas at them, well, then that would be even better."

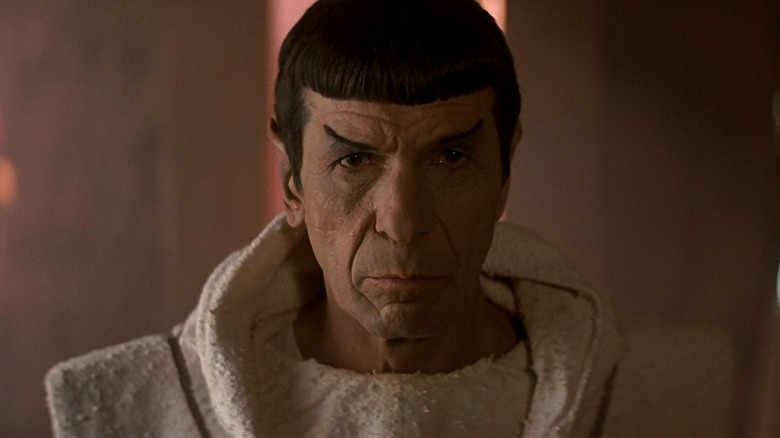

This was, perhaps, a response to the previous two "Star Trek" movies that were loaded with death and violence. "Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan" contained a stereotypical bad guy, a lot of phaser blasts, a lot of shooting, a lot of photon torpedoes, and numerous deaths, including the death of Spock (Nimoy). There wasn't a lot of hand-to-hand combat, at the very least. "Star Trek III: The Search for Spock" was about how the Enterprise crew hijacked the Enterprise in an effort to reunite Spock's disembodied consciousness with a newly grown version of his body. In so doing, however, Kirk's son died, the Enterprise blew up, and the crew went into hiding, knowing they'd be court-martialed.

"Star Trek IV," Nimoy felt, was the perfect time to keep the story light. A time travel story about ecology and biodiversity was just what the doctor ordered, and audiences responded with enthusiasm; the film made $133 million at the box office against its $26 million budget. As stated, it was the most lucrative Trek movie until J.J. Abrams made his 2009 reboot. Perhaps ironically, Abrams' film was the most action-packed Trek film yet and violated all of Nimoy's "Voyage Home" mandates.

What's the big idea?

And, of course, "Star Trek IV" wasn't a dour race against the clock, but a whimsical fish-out-of-water comedy, mining laughs from the 23rd-century Enterprise crew interacting with Reagan's America. Spock confronts a punk rocker in one scene. In another, Kirk (William Shatner) needs to sell his personal effects in order to obtain currency, something no one has in the 23rd century. The lightness only worked in the film's favor.

As for a big idea, Nimoy cleverly made his film an environmentalist screed, arguing that hunting a species to extinction is not logical, and will have unknown, dire consequences for the future. If we don't save the animals on the planet right now, we may be dooming ourselves to an extraterrestrial death hundreds of years in the future. In early brainstorming sessions, Nimoy figured the endangered animal in question should be a small, ugly fish called a snail darter. As the story evolved, the animal in question became a whale, which presented more enticing storytelling options; how does one, for instance, transport a pair of whales onto a starship? And how does one acquire Klingon ship parts in 1986 (as the ship, naturally, required repairs)?

So Nimoy got all six of his mandates, threw in some thoughtful ideas, and came out with the most successful "Star Trek" movie.

It's odd, then, that so many of the more recent "Star Trek" movies have faced "Wrath of Khan" as their template. Four "Trek" movies in a row have been about villains wanting revenge, and each one ended with a violent, deathly fight. Maybe if a 14th "Star Trek" movie is ever made, it too will be a light-time travel adventure about ecology.