How Movie Box Office Actually Works (And How Everyone Gets Paid)

The movie business is a vast, complicated beast. Unless you're on the inside at a Hollywood studio, it can be difficult to wrap one's head around. Even then, it can still be perplexing as it's an ever-evolving maze. The key is that it is ultimately a business based on utilizing the art of filmmaking to try and turn a profit. The biggest part of the equation, now and pretty much always, is the box office.

Though certainly not the only measure of a movie's success, oftentimes, the number of tickets sold versus what it cost to make is the element that determines whether we classify a movie as a hit or not. It's relatively basic math, even though the math is often anything but simple. Just look at a movie like "Bohemian Rhapsody," which the studio claimed lost $51 million despite pulling in more than $900 million at the global box office against a very reasonable $55 million budget.

That's on the extreme end of how lopsided Hollywood numbers can be, but it does get at the idea that the flow of money from theaters to the studios is not as simple as it may seem. So, how does the box office work exactly? How is the total cost of a movie calculated? How is the landscape of the box office changing in the post-pandemic era? We're going to go over all of that and more.

I've been a journalist in the entertainment space for a decade, with box office serving as a major focus for most of that time. Even before that, dating back to my early teens when I had no reason to care, I was obsessed with such matters. I remember being fascinated when "Spider-Man" became the first movie to make $100 million on its opening weekend. So, while I may not be a Hollywood bigwig, I do have a damn decent understanding of how this stuff works. Let's get into it.

How much does a movie cost, really?

The first (and arguably biggest) part of the equation has to do with figuring out what a movie costs to make in the first place. One of the biggest things about using box office as a metric for success is that it's all relative. A $5 million indie movie needs to make a whole lot less than a $200 million blockbuster to break even. Yet, in most cases, a ticket costs the same, unless we're talking about a premium format option such as IMAX or Dolby Cinema. But, in essence, a ticket is a ticket, so the more expensive a movie is to make, the more tickets it needs to sell.

We often hear that a certain movie has a certain budget. For example, "Fast X" reportedly had an astonishingly high $340 million budget, making it one of the most expensive movies ever made. Where does all of that money go? In the case of the "Fast & Furious" franchise, so much of that money goes to pay cast salaries, as the ensemble is full of A-listers who all command big paydays. Then, the director is still on the hook to make a big-budget blockbuster. That's an extreme example but actor salaries are part of a budget. Remember, when you're watching all of those credits roll when a movie is over, never forget that everyone gets a paycheck.

What a budget does not include, however, is marketing money, frequently called P&A (print and advertising). This often is a huge expenditure. The old rule of thumb used to be that you would double the budget to account for marketing on a blockbuster. Since franchise budgets have gotten out of control in recent years, that's no longer the case, but it illustrates how much expense that adds to the bottom line.

Independent movies vs. studio movies

Also worth mentioning is that there are costs that don't get lumped into budgets or marketing. There is general studio overhead, various development costs, and things of that nature that still, ultimately, contribute to what it costs to bring a movie to life. So, when we say that Christopher Nolan made the Best Picture-winner "Oppenheimer" for a $100 million budget, that's not accounting for marketing costs. Hence, it's not as simple as a movie with a $100 million budget needing to make $100 million at the box office to break even. More on that in a bit.

It's also important to go over how films are financed in the first place. There are, generally speaking, two paths to getting a movie made: through a traditional studio or the independent route. For our purposes, I am going to oversimplify this process with the understanding that there is a lot of nuance involved in either case, but I am aiming to offer a general sense of how these two methods of financing differ.

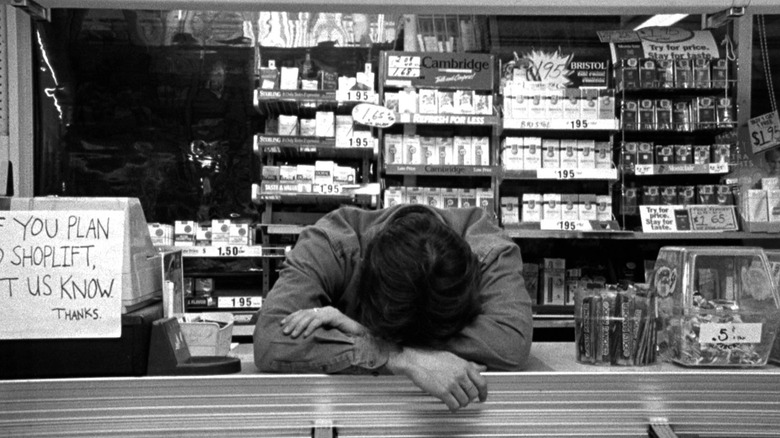

On the studio side, Disney for example might decide to make a new "Zootopia" movie. They will allocate a certain budget to make that happen and that's that. The money comes from Disney. On the independent side, a filmmaker or several partners will try to raise money through various sources to fund a film. Kevin Smith famously maxed out a bunch of credit cards to make "Clerks," which then became an indie darling in 1994 after Miramax bought the rights following its premiere at Sundance.

There are numerous ways an indie film might secure financing but the goal is still to secure a distribution partner that can get the movie in theaters and help make everyone their money back. It's far less straightforward than the studio path and, generally speaking, an indie movie will cost less than a studio movie, depending on the type of movie we're talking about.

What it takes for a movie to break even at the box office

I previously did a deep dive into the rough rule-of-thumb movie math we use in the box office world, but for our purposes here, let's imagine a hypothetical movie with a $150 million budget. Let's use the old rule-of-thumb and double the budget figure to account for marketing and other expenses, which is not unreasonable. That brings the total cost to $300 million. That means this hypothetical movie needs to earn $300 million in revenue to break even. So, how do we get there?

Another rule of thumb is that theaters keep roughly 50% of the money from ticket sales before the studio gets its cut. This changes depending on what weekend, what movie, and what country we're talking about, but the rule-of-thumb often works well enough. Using that math, a movie with a $150 million budget would need to earn roughly $600 million at the global box office to break even.

That's before it ever turns a profit. A smaller movie, let's say a $5 million indie movie, requires much less. However, the marketing for a movie like that is a lot more than $5 million, generally. A Blumhouse horror movie like "Get Out" might cost $4.5 million to make, but the studio will probably spend roughly $20 million or so to market it. So it's break-even number would be in the neighborhood of $50 million worldwide, based on a $25 million investment.

Rough though it may be, this math often checks out. A.Frame offered a rare insight into the actual financials with 2012's "Skyfall." The movie was a huge hit, earning $1.1 billion worldwide. According to the studio's official breakdown, $400 million went to theaters, $186 million to production, $117 million for advertising, $27.7 million for prints, and $24.3 million for other costs. That left $57 million in profits for the distributor, Sony, in this case, and $179 million for MGM, as well as $109 million for the "Bond" rights holders. $345 million in total theatrical profit for a movie that made well over $1 billion worldwide.

What happens when a movie fails to break even at the box office?

Sometimes, things don't go well. So, what happens when a movie fails to profit in theaters or, even worse, flat-out bombs? Then it becomes a bit of a triage situation where it's a matter of figuring out who loses how much. Take last year's "Hypnotic" for example, a movie that cost $65 million (before marketing) that flopped badly. It pulled in just over $16 million worldwide. In instances like this, it's not like the director, in this case Robert Rodriguez, suddenly has to give his salary back, nor do the actors or any of the crew. But this movie had a handful of production companies involved at various levels, all of which have to divide what little profits there are and suffer their percentage of the losses.

We'll talk more about post-theatrical revenue in a bit, but using some of the math from earlier, we can estimate that "Hypnotic" lost at least $75 million in its theatrical run on the conservative end. After theaters took their cut, that left the investors with about $8 million from ticket sales, perhaps closer to $10 million if their cut was more favorable. Even if they launched a modest $20 million marketing campaign, that's still an $85 million investment with at most $10 million worth of ticket sales. It's easy to see how those losses add up.

It's also easy to see how movies with big budgets carry an insane amount of risk. Just look at last year's "Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny," a movie that cost around $300 million before marketing. It only pulled in $384 million worldwide, making it a colossal misfire for Disney. Conservatively, Disney's investment was $400 million or more with marketing costs, while only earning about $192 million — give or take — from ticket sales. That's assuming the marketing spend was kept to $100 million (it may well have been more). We're talking losses north of $200 million from the theatrical run. Again, this is all rough math but it helps paint a picture.

Who gets paid once a movie gets into profits?

Let's say a movie is lucky enough to get into profits purely from its theatrical run — who gets paid and when? This is a very complicated question, one that has been subject to lots of debate and legal action over the years. See our "Bohemian Rhapsody" example from earlier. With a studio movie, it's somewhat cut and dry. Once the studio recoups its investment, the profit goes to those who are contractually due to benefit. Oftentimes, directors, writers, and actors are entitled to royalties based on profit, with the studio taking the lion's share of what profits there are to take. Studio accounting practices often make that tricky.

"Doctor Strange" director Scott Derrickson once said, "I told my attorney the next time you're negotiating my net profit for a movie, ask for a ham sandwich instead." Net profit means that the director or actor gets a percentage of the proceeds after a movie has entered profits. However, as Derrickson explained in a career-spanning interview with /Film, it's not so simple as all of that:

"Net profit is something that is defined by the studios in very creative ways. It sounds good. I think I had a 5% net profit participation in '[The Exorcism of ] Emily Rose.' Like you said, the movie cost $19 [million], it made I think $75 million domestic and about $150 million worldwide, and it is not considered a net profit movie. So there are stories of one or two movies that I've heard of that got into net profits."

For the exceptionally lucky such as Christopher Nolan or Tom Cruise, there is something called gross profit participation. This is sometimes called first-dollar participation. That means, from the second the movie starts its box office run, that person gets a cut, whether it technically profits or not. This is why Robert Downey Jr. made so much money playing Iron Man in the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

How the box office impacts the profitability of a movie beyond theaters

It's incredibly important to emphasize that box office is just a part of the equation. "Dial of Destiny" made money for Disney in other ways beyond theaters, including VOD, Blu-ray/DVD sales, merchandise, and the value it eventually brought to Disney+. That helped close the gap on the losses, even if it probably didn't get the movie into profits. The movies that benefit the most are ones that are on the borderline from ticket sales alone.

Take 2023's "Transformers: Rise of the Beasts." It made $439 million worldwide against a budget in the $195 million range. That's not coming close to breaking even at the box office based on our rough math. That said, Paramount sold a lot of merchandise because of that movie, and it helped reinvigorate interest in the rest of the "Transformers" films again. That all brings value beyond the box office. Similarly, "Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Mutant Mayhem" made $180.5 million worldwide against a $70 million budget but, as producer Seth Rogen put it, "sold $1 billion worth of toys."

More importantly, the better a movie does at the box office, the better it will do in every window after theaters. Movies that make money in theaters, even if they don't outright profit, do better on VOD and on streaming. They sell more Blu-rays, move more merch, and help ensure that the film has a future on shelves for years to come. On the flipside, a movie that is dumped straight to Netflix can easily be forgotten mere weeks after it first arrived.

Even Blu-ray/DVD isn't as dead as some might think. Kevin Smith's "Clerks III" was made by Lionsgate purely because "Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back" sold so many Blu-rays. That's value beyond the box office. Even a giant flop such as "R.I.P.D." eventually got a direct-to-video sequel because the post-theatrical numbers suggested that there was enough of an audience for the franchise to justify a low-budget offering.

It all comes back to the box office

All of this still comes back to the box office. A movie that flops in theaters is all but assured to make less money through all of these revenue streams, even if bombs like "Madame Web" can sometimes go on to find traction on Netflix. That doesn't make up for the millions lost in theaters, nor does it mean that anyone was flocking to stores to buy "Madame Web" merch, which is a big part of the math for superhero movies.

The streaming era has complicated this math a bit at times. Something like Apple's "Fly Me to the Moon" is a great example. It's a $100 million movie distributed by Sony that opened to just $10 million domestically. Yet, Sony is getting a fee for distribution, whereas Apple is carrying all the risk. But a company with a $3.6 trillion market cap doesn't care if this movie makes sense purely as a theatrical play, as they ultimately care about Apple TV+. Streamers releasing movies in theaters throws the whole hit/flop equation out of whack.

Even so, the rough math and rough explanation of how money flows through the movie business laid out there can help offer a better understanding of what box office numbers mean. This, in turn, can help viewers understand why certain movies get sequels, why others don't, and why Hollywood simply doesn't make certain types of movies. It pretty much always comes back to the box office.